Guest post by Mitch Clark

We are pleased to announce the addition of two new exciting collections to the JKBooks eBook platform at University Libraries: the Dai-ichi Koto Gakko Koyukai Zasshi (published by The Museum of Modern Japanese Literature) and the Kobunso Taika Koshomoku (a major corpus of antiquarian book catalogs). Both of these collections will be useful to scholars investigating topics related to early 20th century culture, especially youth culture, education, literature, and philology. With the addition of these titles, the number of online JKBooks collections now reaches a grand total of thirteen available to OSU users. Below is a short description of these collections as well as some highlights and screenshots of their contents.

Dai-ichi Koto Gakko Koyukai Zasshi (第一高等学校 校友会雑誌)

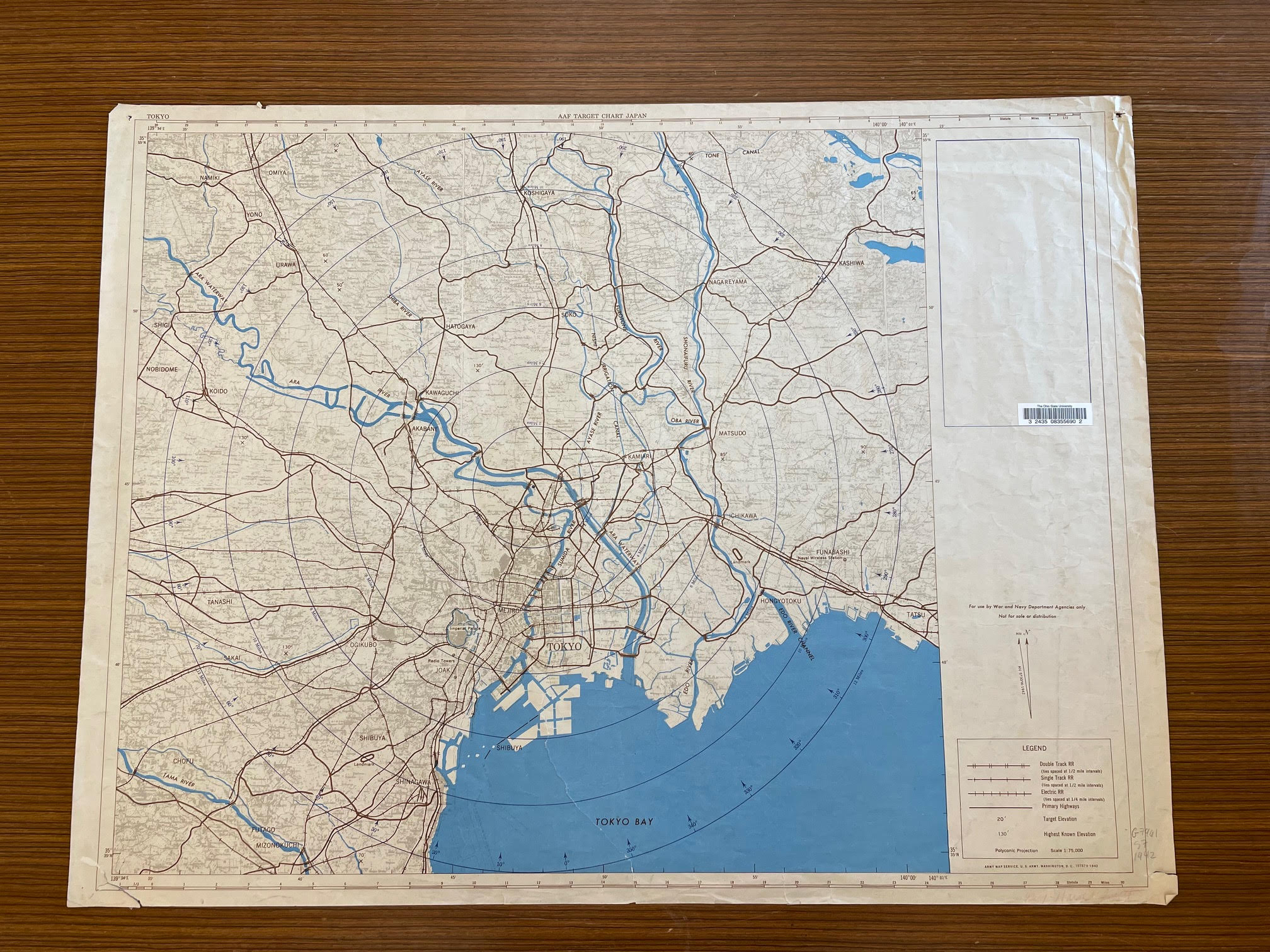

Two Sample covers of the

Daiichi Koto Gakko Koyukai Zasshi

The Dai-ichi Koto Gakko Koyukai Zasshi is a magazine published by First Higher School of Japan, a former preparatory boy’s boarding school in Tokyo and one of Japan’s most elite institutions of the modern era. Published from the Meiji period until during WWII, the database offers all but 2 issues (380 of 382 ever published) of the magazine. (Issues No. 293 and 295 of 1923 (Taisho 12) have not been found and are therefore not included in the collection).

In the publisher’s words, this “magazine vividly records the mentality fostered within this elite high school” from the pre-war period until World War II. In addition to leading artists and literary figures, many of the students of this school eventually became prominent leaders in academia, politics, the economy, and education. The repository thus “stands as a spiritual record of the youthful times of those figures” during much of Japan’s modern era (1890-1940).

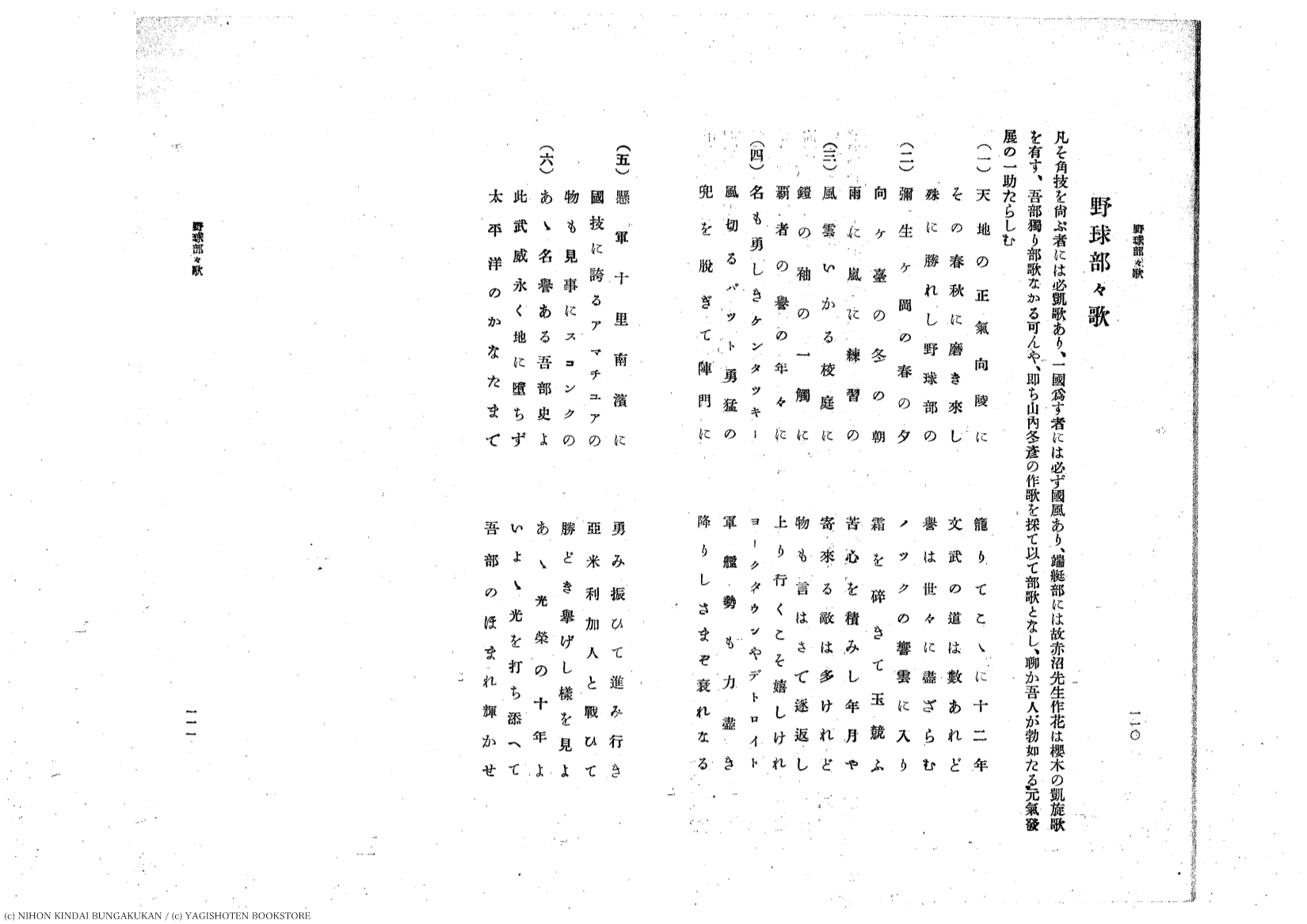

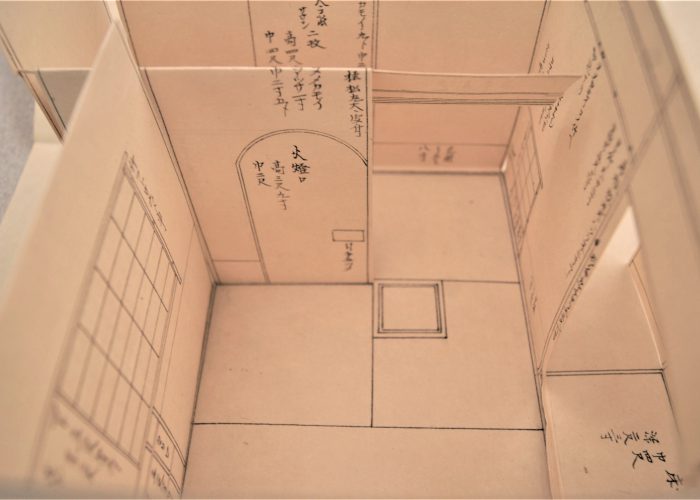

Among other topics, the journal overflows with poetry and prose written by such luminaries as Jun’ichiro Tanizaki (谷崎 潤一郎, Tanizaki Jun’ichirō, 1886 – 1965) and Yasunori Kawabata (川端 康成, Kawabata Yasunari, 1899 – 1972) during their high school days. While many of the issues emphasize the arts, its diverse contents will be of interest to wide-ranging scholars from many disciplines including the social sciences. Some of pages that stood out to me, for instance, were those with multiple essays (as well as a team fight song) about the school’s baseball club in the early Taisho period. An analysis of such sources can certainly help in constructing a more vivid image of early baseball culture in Tokyo and Japan!

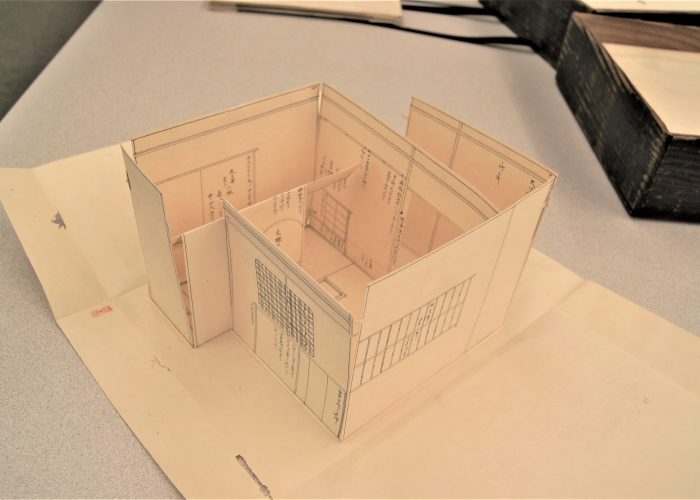

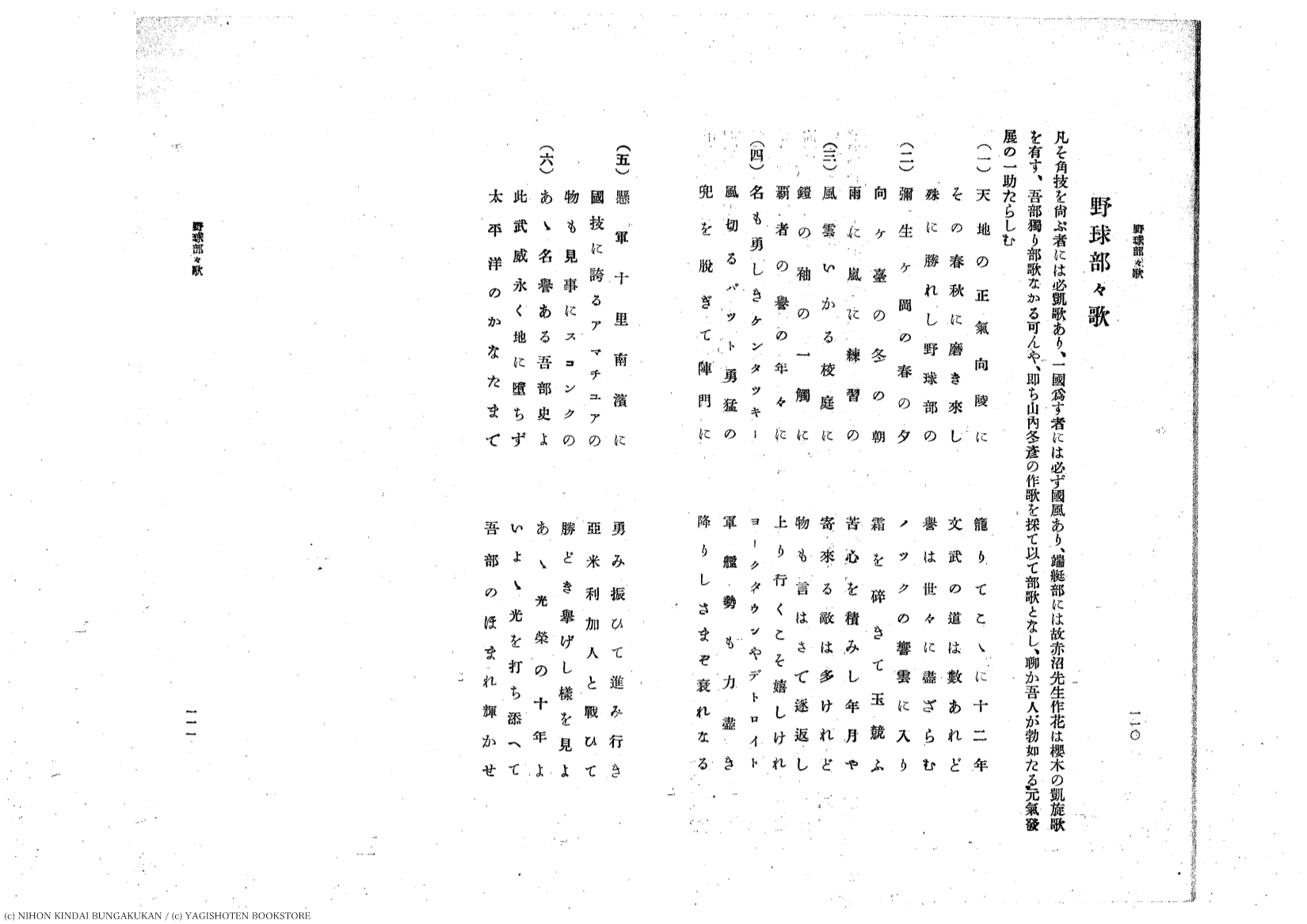

Screenshot of the school’s Baseball Club Fight Song, Supplement Issue No. 2, February 28, 1909, pp. 110-11.

Kobunso Taika Koshomoku (弘文荘待賈古書目)

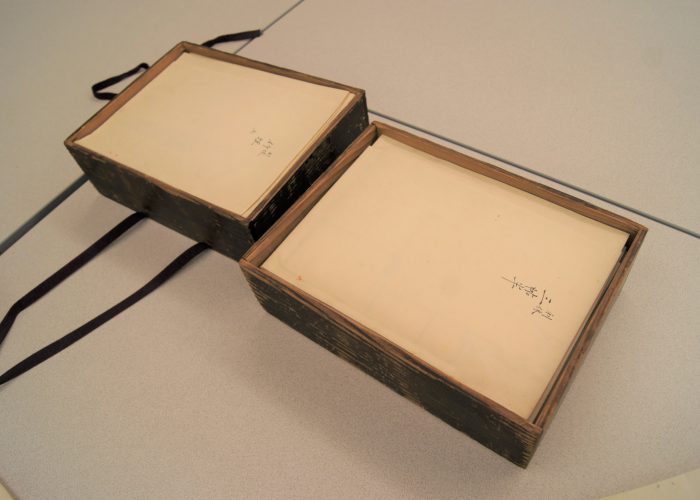

Two Sample covers of the 77-volume

catalog Kobunso Taika Koshomoku

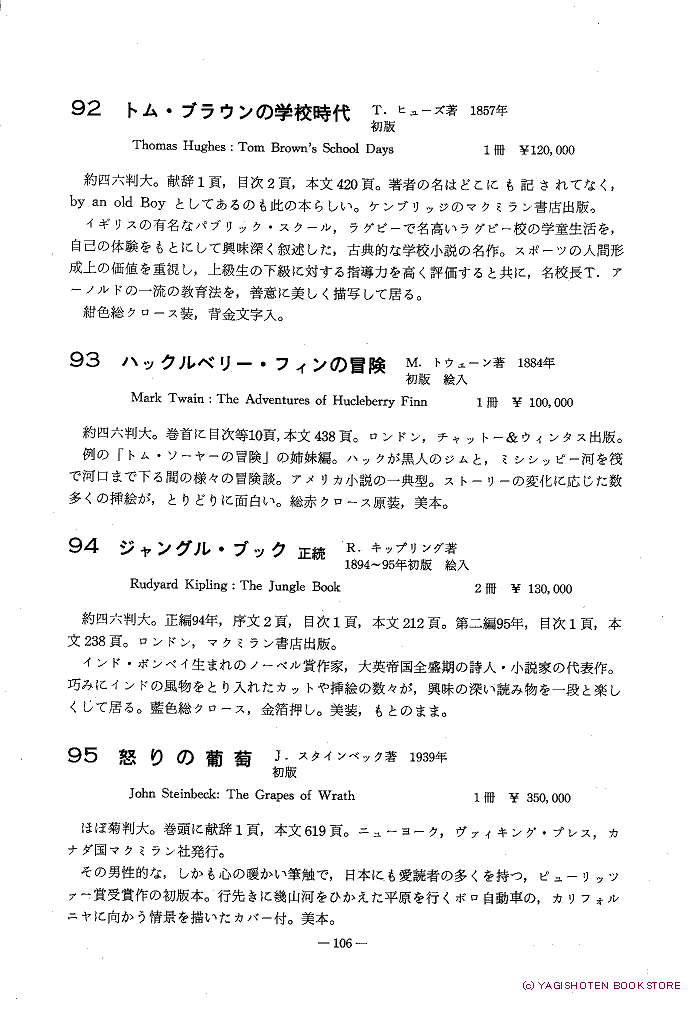

The Kobunso Taika Koshomoku is a 77-volume catalog collection that lists approximately 20,000 antiquarian books. Distributed to customers of the vintage bookstore “Kōbunsō” founded by Shigeo Sorimachi (1901-1991), the volumes were originally published between 1933 and 1984 and filled with detailed bibliographical information, illustrations, and publishing histories. They are therefore an especially useful reference for scholars of philology and bibliographical studies.

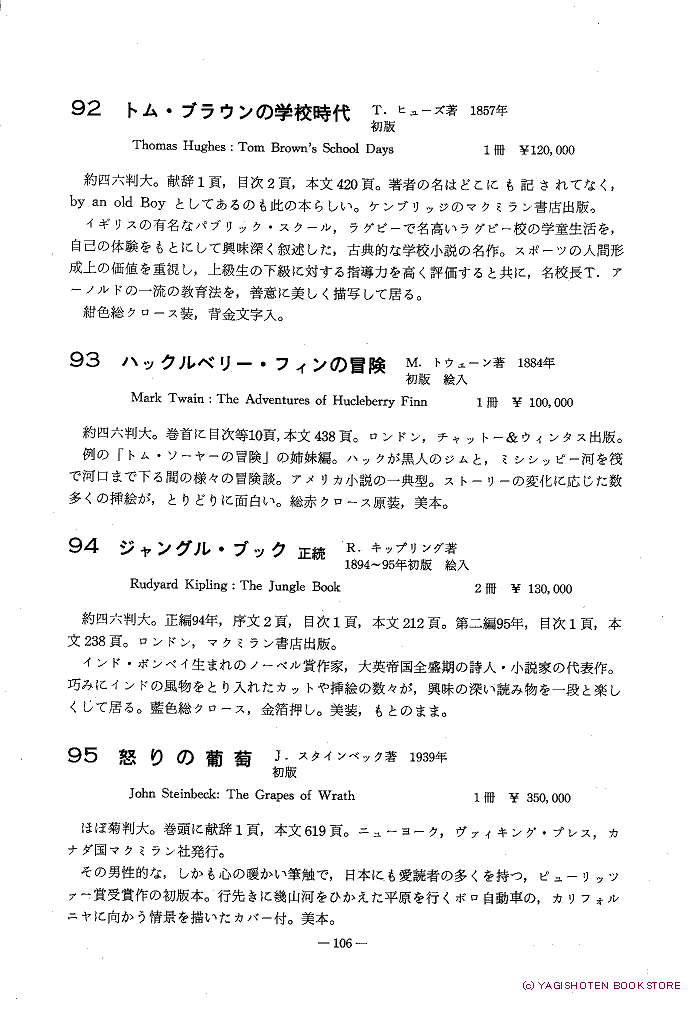

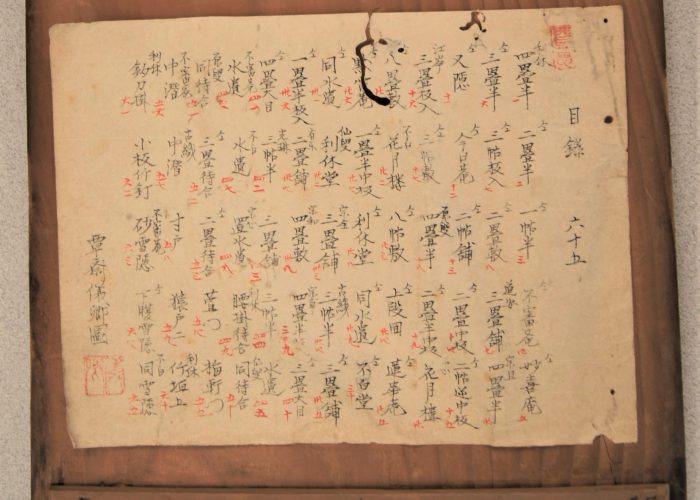

In my first browsing of the catalogue, I stumbled upon some Western classics. Entries 93 through 95, for example, list first edition copies of such famous English language books as The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain, The Jungle Book by Rudyard Kipling, and The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck.

Entries 93-95. Kobunso Taika Koshomoku, No. 48,

Showa 51.01 (January 1976), pp. 106.

JapanKnowledge Books (aka JK Books) is an ever-expanding eBook platform hosted by JapanKnowledge (an online treasure trove in its own right of Japan’s most important dictionaries and encyclopedia). For an overview (or just a refresher) on “JKBooks,” please take the time to visit this past blog. The list below shows a list of the newest collections (marked with *) along with the many others offered through our library.

1. Taiyo

2. Bungei Kurabu: Meiji-hen

3. Dai-ichi Koto Gakko Koyukai Zasshi*

4. Takita Choin kyuzo Kindai sakka genkoshu

5. Fuzoku Gaho

6. Gunsho Ruiju series

7. Bijutsu Shinpo

8. Toyo Keizai Shimpo / Weekly Toyo Keizai Digital Archives

9. Kobunso Taika Koshomoku*

10. Jinbutsu Sosho

11. The ORIENTAL ECONOMIST Digital Archives

12. Kamakura Ibun

13. Bungeishunju Archives

If you have any questions regarding JKBooks, or any other resource offered for Japanese Studies at the OSU Libraries, please contact us!