It’s Mother’s Day today in the United States, which means that many mothers in the States are opening letters and cards given to them by their children in honor of today’s holiday. Mothers play a critical role in the lives of their children. This was just as true in the past as it is in the present. Every explorer that made history exploring the polar regions and made contributions to science through their efforts was also someone’s child. In honor of Mother’s Day, we’d like to share a few (of many) items in which explorers write to their mothers and share with them their experiences.

Sir George Hubert Wilkins, before exploring the polar ends of the Earth, served his country as an official photographer for the Australian War Records Section during the First World War. Writing a few months before the end of the war, Wilkins explains to his mother his thoughts and experiences with enemy prisoners under his care. Sir George Hubert Wilkins Papers: Box 12, Folder 6.

8/28/1918

Dear mother,

You will have seen by the papers that we have been pretty busy over here, so busy in fact that I have not written a private letter for three weeks until today. Two of my staff; I have fifteen now are in hospital and it makes ever so much more work for me. They are not seriously ill however and may soon be back at work again.

The happenings for the last few weeks makes it seem that the tide has turned. And that we may… at last that we are on the road at last toward making the enemy understand that we mean to fight to a finish. It may not take long but now I’m sure that everyone wants to go on until the job is done.

I think I told you before that I do not carry arms for fighting yet I have captured two prisoners lately myself. They have been hiding when others went past and came out and surrendered to me.

It is curious to feel you have the custody of another man who would have, a few minutes before, done his best to kill you but after all we all are human and have yet to find a really blood thirsty enemy.

Many of them now are glad to be captured and some seem to think they have much chance against our numbers.

If only the people at home could see the war as the soldiers see it the war would soon be over. I have received with pleasure several of your letters lately and look forward to them anxiously. You maybe by now have seen some of our work on exhibition in Australia. Anyway it will be there soon.

Much love from your loving son,

George

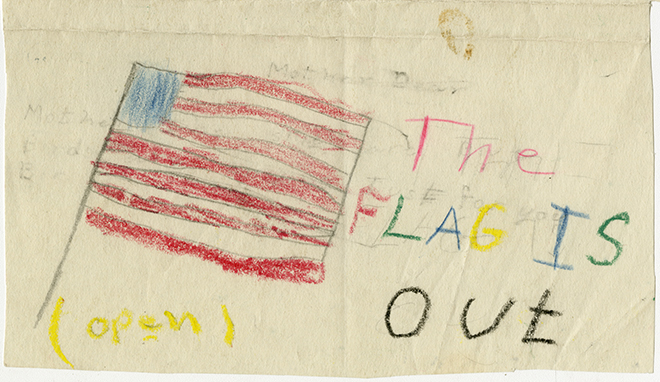

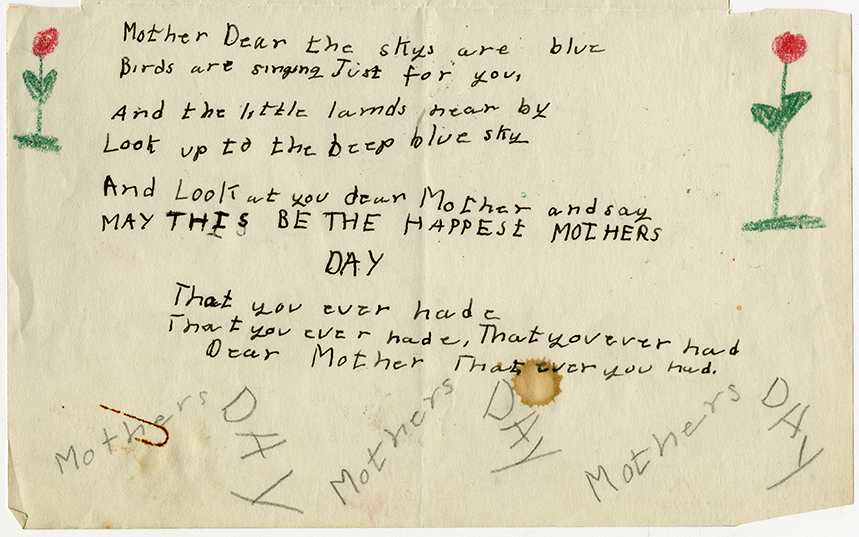

Admiral Richard E. Byrd‘s wife, Marie Donaldson Ames, probably received this handmade card from her children, Richard, Evelyn, Katharine, and Helen, around the time of one of Admiral Byrd’s early expeditions. Richard E. Byrd Papers: Box 29, Folder 1299.

Admiral Richard E. Byrd‘s wife, Marie Donaldson Ames, probably received this handmade card from her children, Richard, Evelyn, Katharine, and Helen, around the time of one of Admiral Byrd’s early expeditions. Richard E. Byrd Papers: Box 29, Folder 1299.

Richard Lockhart aboard the USS Pine Island as an naval ensign during Operation Highjump (1946-1947), which was was the largest expedition into the Antarctic to date and was the first expedition to Antarctica officially sponsored by the United States in over a century. Richard Lockhart Papers: Box 1, Folder 2.

January 17, 1947

On ice fields of Cape Dart

Dear folks,

The destroyer “Brownson” is coming alongside for provisions today or tomorrow and will take off some mail and will then transfer it to the states somehow.

You have probably been getting all sorts of news from the expedition especially concerning the missing plane from the Pine Island. As you no doubt know, we found them and they are being sent back to the states with this letter. All the survivors except Captain Caldwell are being sent home, as the skipper don’t want to leave the ship. As you also know, three of our boys won’t be back, among them Ensign Lopez, a good buddy of mine, who now lies buried in the snow on Cape Dart.

We have been ice bound for the past two weeks but it looks as if we may be able to move further south in a short while which will put us in totally unexplored and uncharted waters. I am keeping up a chart of the Antarctic and am plotting in our positions every so often. Don’t worry, I’ll have plenty to show you and all yours when I get back.

I sure do miss all of you and feel so awfully far away down here. It is now thirty-seven days since we last saw land! And it will be a heck of a lot more, too. All we see is ice, ice, ice. When I get home, if you have iced tea, don’t put ice in mine. I am inclosing a picture which I took and developed myself to give you a rough idea of the ice we have; this is a shot of a huge ice berg we just missed.

Not much more news except that I am O.K. and in good health. Tell everybody hello for me and take care of yourselves.

Well, that’s about all for now. So be good and I’ll see you. Oh, by the way, a promotion list came out and I just missed it. In about four or five months, you’ll; be calling me Lieutenant.

Love to all,

Dick

Donald L. Jeanroy participated in Operation Deep Freeze I, II, and III, which were United States military missions that dated from 1955-1958 undergone to support the scientific expeditions of American scientists. Around the time of this letter, Jeanroy likely had just left the Machinist Mate School, Great Lakes National Training Center in Illinois to report to the USS Arneb. Donald L. Jeanroy Papers: Box 1, Folder 4.

May 8, 1955

Dear Mom,

Happy Mother’s Day to you, Mom! I hope you are well and happy on this bright and cheerful Sunday afternoon.

Well, tomorrow morning I’ll be boarding the USS Arneb, starting my three and a half years of cruising the world. We’ve waited down here at Norfolk for over a week for this ship to come in and yesterday when we went down to the piers there she set “AKA 56”. It looks like a great big, scufty son of a gun, which has really seen the roughest of seas and mightiest of battles. But all this shine and glitter will soon where off once I get aboard. This boy from Texas and myself went down to the pier and was talking to the dock watch off of the Arneb. He said that the old ship really gets around. She has just gotten back from the Carilion, bringing down a load of supplies to the marines down there. He also said that in mid-July we’re going up to Greenland for maneuvers until October and then we’re coming back to the States for a few days and then we’re going down South again. But this time, way down Sough. They call the cruise “Expedition Deep Freeze” to the Antarctic for six months to a year. I shake at the thought of going way down there but it’s a place that not many people can say they’ve been at. Especially traveling by cargo ship.

You might wonder how all this information gets around. Well the Bureau of Ships in Washington makes up a schedule for each ship, a year in advance, and then passes the word along. It’s only during wartime and secret missions that this info isn’t given out. There are a few other minor operations that the Arneb is going to get but I can tell you more about it when I get aboard.

The liberty down in this place is terrible. In Norfolk there is no type of entertainment, women or pass-times which are worth our while going to. We went down last Saturday to see the town. After we walked up and down the couple of main and side streets, and a stroll through the colored sector we went into a bar and spent the rest of the evening there, listening to the jukebox and drinking beer. We’ve found out since that that’s the only thing you can do in that town.

Yesterday, a couple of fellows and myself went over to Newport News to see the carrier Forestal and the naval shipyard over there. We couldn’t get into see neither but we got a good view of the Forrestal. It sure is a big hunk of ship and a mighty powerful weapon in war. I took my camera along and got a few pictures of it but I don’t know how they’ll turn out. We have to come back from Newport News by ferry. When we got on it was just about sunset, the prettiest part of the day. So we rode the thing back and forth three times all on the same 20₵.

Today we’re just hanging around the base, trying to find something to do. Later on tonight we might go downtown and have a few beers. I’ve found out that this town surely deserves its name of “Shit City”. The people down here are as unfriendly as hell (not like Milwaukee) and when we do find one that will talk we can’t understand them with their Rebel talk (accent). But we really have ourselves a ball when we meet some trueblooded Yankee, we all talk the same language then.

The USS Iowa was in port last weekend but I didn’t get a chance to go aboard to see Billy Milligan. It was long gone when I went down the following Monday to see it. But I’ve been aboard a couple of other ships and seem quite a few buddies from boot camp. When we go aboard they show you all around the ship from stem to stern. Last Friday night this kid from Cincinnati, Ohio and myself went aboard the battleship Wisconsin and saw most all the whole ship. Those ships are surely built to precision and to a lot of expense.

Well to get down on the ground again, how are things going back home? I haven’t heard anything yet because all the mail is probably over aboard ship I hope things are okay. Have you gone into New York for the medical check-up yet and when are you going to see Min and Eric and the rest of the family in Chicago? When you do go travel only airplane. Never by bus of train, except when you’re going on a short hall. Take the word of advice from the “Traveler” himself.

Well it looks like I’ve just about ran out of words. I’m sending you a clipping from the base newspaper telling about the Arneb’s Antarctic cruise. Maybe you can save it for me or put it in a scrapbook or picture book for safe keeping. It’s a nice little souvenir.

So I’ll sign off about here but until I write again or hear from you it with lots of

Love, Don

P.S.: Send my love to Nancy and Claudette and a hello to Bob and Alice for me

Don

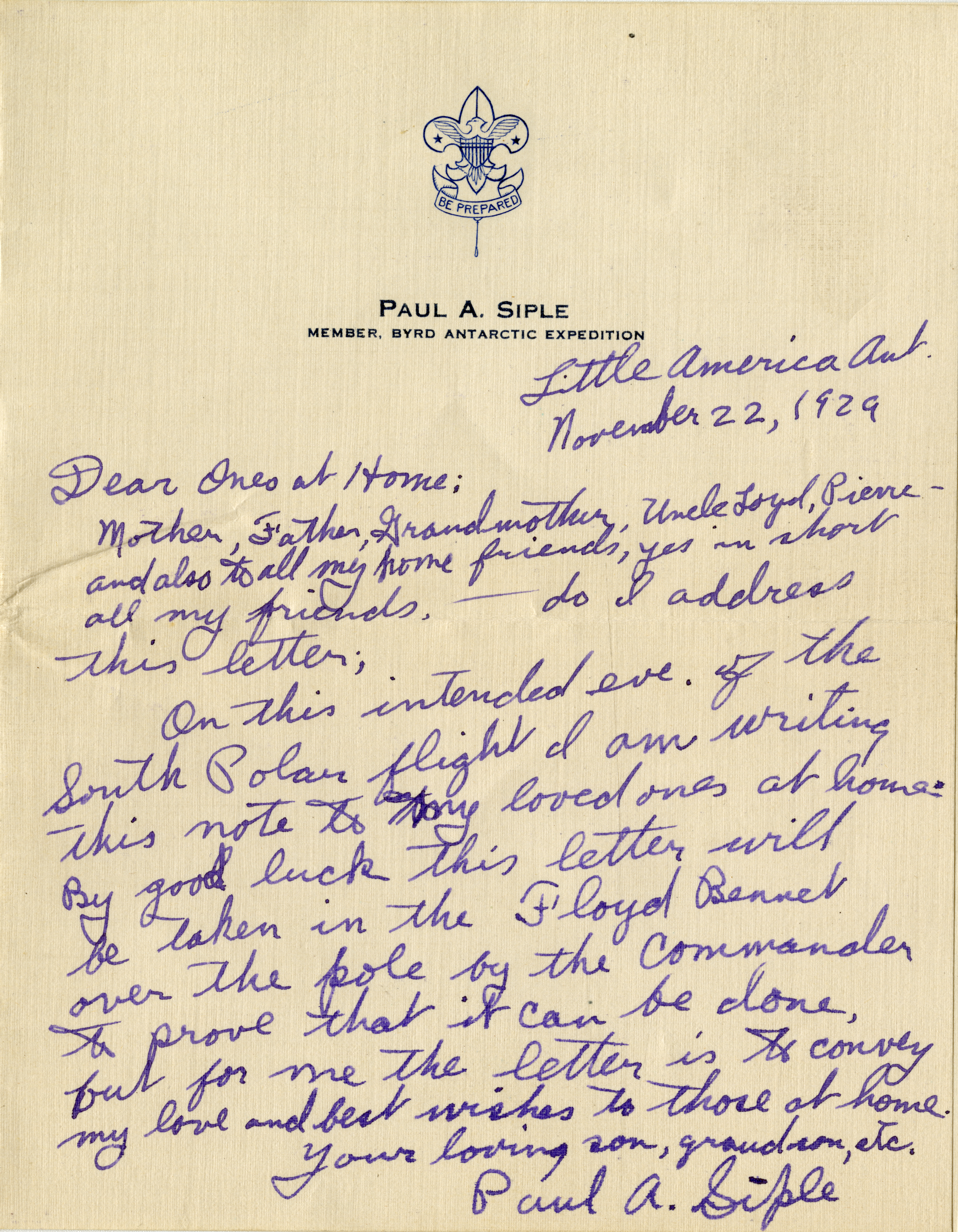

Paul A. Siple was the “Boy Scout with Byrd”, the young man who was selected to accompany then-commander Richard Byrd on his first expedition to the Antarctic (1928-1930). On that expedition, Byrd made his historic flight over the South Pole, something no one had done before. Siple was only nineteen when he became a part of this expedition. Paul A. Siple Papers: Box 3, Folder 2.

Little America, Antarctica

November 22, 1929

Dear Ones at home:

Mother, Father, Grandmother, Uncle Loyd, Pierce- and also to all my home friends, yes in short all my friends- do I address this letter;

On this intended eve of the South Polar flight I am writing this note to my loved ones at home. By good luck this letter will be taken in the Floyd Bennet over the pole by the Commander to prove that it can be done. But for me the letter is to convey my love and best wishes to those at home.

Your loving son, grandson, etc.,

Paul A. Siple

Well, that’s all for the Polar Archives today. Be sure to check out our newly redesigned website and have a look around all of our collections! Happy Mother’s Day!

Written by John Hooton

Recent Comments