This blog post is part of the Frozen Friday Series, an A-Z journey of the Polar Archives. Each week, we will feature some aspect of the history of polar exploration with a blog post written by our student authors

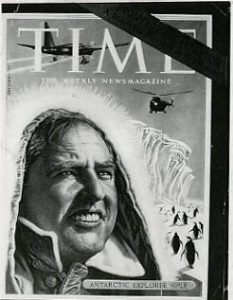

While doing research for another Frozen Fridays post (“‘O’ is for Outreach”), I came across a source written by a familiar name: Siple (as in Dr. Paul Siple). Puzzled by the familiarity, I summoned the “Googler” and sought to solve my self-created mystery. Upon skimming Paul Siple’s Wikipedia page, I arrived at my answer: Paul Siple, apart from his significant contribution to the development of what would commonly be known as the wind-chill factor, was also the famous Boy Scout that went with then Commander Richard E. Byrd on his first expedition to Antarctica (1928-30). With some excitement at this discovery, my curiosity succeeded in derailing me from my research and drove me to the Polar Archive’s website, seeking a short biography of the man. While Dr. Paul Siple did have a collection in the Polar Archives, to my disappointment, no such bio yet existed. With this week’s blog, I intend to rectify that by writing a bio pro tempore that will bring attention to one of the many interesting individuals within the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center Archival Program.

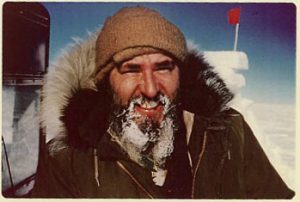

Paul Allman Siple, born on 18 December 1908 in Montpelier, Ohio, would be one of the few men to have the distinction of serving under Admiral Richard E. Byrd on all five of his Antarctic expeditions.[1] On the first of these expeditions, the young Paul Siple was a plucky nineteen year-old, fresh from his first year of college.[2] In June 1928, Chief Scout Executive James E. West announced that Commander Richard Byrd was looking for a single Boy Scout to serve with him on his upcoming journey south.[3] Of the 826,000 scouts, eighty-eight were recommended to the National Office of the Boy Scouts, which in turn narrowed the selection pool to seventeen. A further committee narrowed the seventeen to six finalists.[4] The most basic considerations for any scout applying for this coveted position were rigorous: at least two years of First Class or Able Sea Scout rank in the Scout Movement, two recommendations from “qualified authorities” on his character and skill, and Merit Badges in various skills such as Aviation, Hiking, Machinery, and Taxidermy.[5] Obviously, the final six Scouts held all of those qualifications and more. The final selection memo sent to Chief Scout Executive James West detailed each of the six, listing the strengths and weaknesses of each boy. Paul Siple received more than double the average number of strengths while fewer than the average number of weak points. Described in the memo as having “a good strong physique” and an “excellent character with the highest ideals,” Siple appeared to the selectors to be intelligent, sincere, respectful, and generally very well suited to the tasks of the expedition. Even his weak points were positive: “He is not a rapid thinker. He takes time, but is usually right. He is a little too serious…He accepts criticism appreciatively, however.”[6] It appears that Paul Siple was the clear choice for the expedition.

Siple nearly missed the opportunity to winter on the continent. “‘Nobody knows who is going to stay on the ice,’” said Siple, quoting then Commander Byrd. “‘Everyone who does will have to have a reason. Besides, we do need crew members to bring the ships back for us at the end.’”[7] Luckily, Siple’s training as a Boy Scout came once again to his aid. Larry Gould, second in command of the expedition, “had promised the American Museum of Natural History that he would bring back a barrel each of seal and penguin skins,” an obligation that Gould no longer felt he could complete. Thus, when Gould sought someone to take on the messy task, Siple was first to volunteer. After pleading to the good Commander to allow the boy to winter on the ice, Siple joined the winter party as a “taxidermist, dog driver and naturalist.”[8] Siple would also become the driver of his own dog team when one the expedition’s dog handlers suffered “an unfortunate accident.”[9] Siple recounted his adventures as a Boy Scout with Byrd in his books, A Boy Scout with Byrd and 90⁰ South. Perhaps the most amusing of these tales is the story of how he gained a “knighthood”. Siple was a founding member of the “Knights of the Grey Underwear” when, out of necessity the winter party engaged in a process known as “dry washing”. Siple explains: “In the cold of the winter the process we called ‘dry washing,’ or exchanging soiled clothes for almost equally soiled garments which had previously been set aside for laundering but which now looked somehow cleaner than those being worn, came into existence. And so the “Knights of the ‘Grey Underwear’ was born.”[10]

Upon returning to the United States, Mr. Siple would become Dr. Paul Siple after completing a doctorate in geography from Clark University. He would serve on all of Admiral Byrd’s expeditions to the Antarctic and devised, with Charles Passel, the wind-chill index that measures the effect of moving air on the human body.[11] Paul Siple lived an incredible live and had the privilege of serving with Admiral Byrd for nearly the entirety of his adult life. Paul Siple’s collections and the collections of other Polar Explorers, including the good Admiral, can be found at the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center Archival Program.

Written by John Hooton.

[1] Jeff Rubin, “Siple, Paul,” Encyclopedia of the Antarctic (New York: Routledge 2007).

[2] Information taken from the Papers of Admiral Richard E. Byrd.

[3] Information taken from the Papers of Admiral Richard E. Byrd.

[4] James E. West, “With Byrd to the Antarctic”, Boys Life, October 1928, 17.

[5] Information taken from the Papers of Admiral Richard E. Byrd.

[6] Information taken from the Papers of Admiral Richard E. Byrd.

[7] Paul Siple. 90⁰ South (New York: Putnam 1959), 40.

[8] Paul Siple. 90⁰ South, 41.

[9] Paul Siple. 90⁰ South, 42.

[10] Paul Siple. 90⁰ South, 43.

[11] Jeff Rubin, “Siple, Paul.”

Recent Comments