This blog post is part of the Frozen Friday Series, an A-Z journey of the Polar Archives. Each week, we will feature some aspect of the history of polar exploration with a blog post written by our student authors.

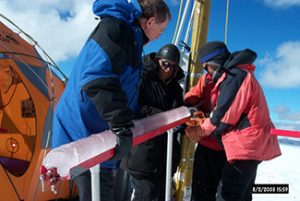

Lonnie Thompson at Qori Kalis glacier. His research

team has been measuring the melting of this glacier

over the last 20 years. Elevation of the Quelccaya ice

cap is 18,700 feet. Peruvian Andes, August 2000.

We would like to apologize for last week’s hiatus. We were in the process of producing a very special mini-series within this Frozen Friday blog series. I had the pleasure and honor to interview Dr. Lonnie Thompson, a leading glaciologist, an outspoken climate scientist, and one of the friendliest, most approachable men I have ever met. The interview lasted for over one hour and was, in all honesty, one of the most interesting and fun experiences I have had while working with the Polar Archives. The reason we had decided to conduct an interview for this post is because Dr. Thompson is a living, breathing explorer. While we can guess at what drove Admiral Byrd or Dr. Cook to explore, we can easily ask Dr. Thompson why he does what he does. So, that is what I did. A full transcript of the interview can be found here.

Over the next four weeks, we will be publishing one of four blogs highlighting portions of the interview. Each post will focus on a theme from the interview and feature highlights of that particular section. This post will focus on introducing Dr. Thompson, in his own words, to those who might not already know of him. Next week will be about the difficulties he faced when beginning the Ice Core Paleoclimatology group here at the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center.

How would you describe what you do and what you study to someone who wouldn’t know, just in your own words?

I’d say, first and foremost, we study glaciers… Glaciers are wonderful recorders in that every year, if you’re high enough, cold enough, or in high latitudes where it’s cold enough, you get an annual layer of snow deposited. You can measure that layer through measurements of isotopes of oxygen and hydrogen that tells us the temperature of the past so you can actually see the seasonal cycle in these areas…Every dry season, if you’re in the tropics, you get a layer of dust. You can measure the thickness of those dust layers through time and you can reconstruct precipitation… Literally anything in the atmosphere is recorded in the ice and that’s including the atmosphere itself. In the little bubbles (capsules) in the ice is capsules of the atmosphere of the past so we can extract the gasses from those bubbles so we can measure carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide; all the greenhouse gasses we’re concerned about today. We can look at how natural variation has changed through time. That record now goes back over eight hundred thousand years… But glaciers also respond to climate change. They’re indicators. If it gets warmer or drier, the glaciers will retreat. When it’s colder or wetter, they advance…They’re a visual recorder of how the system is changing… So they record so many variables and they’re the richest recorder that we have on the planet. Unfortunately in today’s world, those recorders are disappearing because the Earth is getting warmer.

I know you do a lot of travel and studying. I know the Byrd Center prides itself on having ice cores from various places. You said you’ve been to Greenland, where else have your studies taken you?

Well we have drilled the ice fields of Kilimanjaro in Africa, the highest tropical mountain in Africa. We’ve drilled the ice fields down in through the Andes of Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador. The highest tropical mountain on Earth is Huascarán. It’s one of our drill sites in the Andes in Peru. We’ve drilled in places where people don’t even know there’s a glacier. For example, in Papua, Indonesia in what used to be called New Guinea, in the middle of a tropical rain forest, there’s a glacier, very difficult to get to and that glacier is disappearing very rapidly in today’s world but we were able to drill there in 2010. A lot of what we do is like a salvage mission to capture the history in the ice before it disappears. China, Tibet: we went into that part of the world right after relations were normalized between the U.S. and China. We’ve now been working there for thirty-three years and drilling in the Himalayas and across the Tibetan plateau. We just completed a project in 2015 in the far western Kunlun Mountains where we expect to have the oldest ice archive outside of the Polar Regions recovered on earth. We don’t know yet how old it is, but it might actually be the oldest ice on earth. That’s the beauty of what we do: we go to places where no one has gone before and in those areas you are almost guaranteed to find something new and exciting when you start reading that record.

Published by John Hooton

Recent Comments