This blog post is part of the Frozen Friday Series, an A-Z journey of the Polar Archives. Each week, we will feature some aspect of the history of polar exploration with a blog post written by our student authors

A photograph can be a powerful thing, but it is a very simple concept to understand: a device takes in light and captures the light of a moment in a tangible form that can be printed and viewed over and over again. At their most meaningful, photographs can represent something deeply emotional. They can represent a moment in life and thus a nostalgic focal point. Imbued in the image are the sights, sounds, and feelings of a different time. Photographs can be a source of identity, representing something far more than just an image on a rectangular plane. They can bring a sense of reality to locations that would otherwise exist in the ethereal.

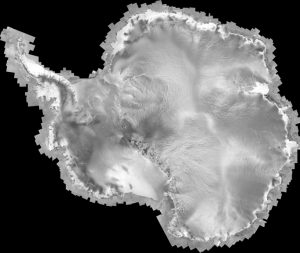

In this way, a photograph of Antarctica would represent something greater than just a new image of Antarctica. In a way, it would make Antarctica more real, like how a photograph of the Grand Canyon might make it seem more than just a place on a map. Yet it would be greater than that. Photographs of Antarctica from space are notoriously poor. Cloud cover always obscures Antarctica and, for about half the year, the darkness of the austral winter hides the continent.[1] Thus, photographing Antarctica in any fashion has proved a particular challenge for scientists. That is, until 1997, when the RADARSAT Antarctic Mapping Project provided the first high-resolution views of the entirety of Antarctica.[2]

Canadian RADARSAT-1 was the combined effort of the Canadian Space Program, which developed the satellite, and NASA, which launched the satellite from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. Equipped with a C-band Synthetic Aperture Radar, which allows the satellite to take high-resolution images of the surface of the Earth regardless of the day/night cycle and any otherwise inclement weather.[3] Launched in 1995, RADARSAT-1 provided information and images of the Earth for many purposes, such as agriculture, cartography, and disaster management, until it ceased to be active.[4]

RADARSAT-1 took thousands of rectangular images

of Antarctica which ultimately resulting in a mosaic

of the continent.

Scientists at the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center (then just the Byrd Polar Research Center) saw the potential RADARSAT-1 had for a breakthrough in mapping Antarctica. The satellite could be ordered to maneuver in space from Earth in such a way that would allow for imaging of the elusive southern continent.[5] Dr. Kenneth Jezek led the team from the Ohio State University that led the overall project and provided scientific direction as well as producing the final products. The first Antarctic Imaging Campaign, as the initial stage of the RADARSAT Antarctic Mapping Project was known, utilized RADARSAT-1’s capabilities to maneuver and capture images despite conditions that would otherwise make image taking impossible. The campaign was completed nine days before it had originally been planned to end with minimal difficulties.[6]

The result was a rather large number of images representing many rectangular images if portions of Antarctica. The images were processed and combined by the Ohio State University team of scientists and resulted in a mosaic image of the frozen continent. In the words of Dr. Jezek, “the RAMP mosaic…is truly a new view of Antarctica.”[7] The mosaic allowed scientists to examine in great detail the geology and glaciology of the continent and provides a bench mark for scientists to judge future changes in the Antarctic ice sheet.[8]

The RADARTSAT-1 Antarctic Mapping Project (RAMP) resulted in a new picture of Antarctica. We can now see the continent through the clouds that kept it shrouded for so long. Scientists studying the Antarctic can use the images produced by RAMP to judge the state of the continent. For the rest of us, however, the image can make the continent more of a real place.

Dr. Jezek and many other polar scientists and explorers have collections at the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center Archival Program, so come check us out!

Written by John Hooton.

[1] Kenneth C. Jezek, “RADSARSAT Antarctic Mapping Project,” Encyclopedia of the Antarctic (New York: Routledge 2007).

[2] Jezek, “RADSARSAT Antarctic Mapping Project.”

[3] Kenneth C. Jezek, “RADARSAT-1 Antarctic Mapping Project,” accessed March 15, 2017, http://research.bpcrc.osu.edu/rsl/radarsat/radarsat.html

[4] “RADARSAT-1”, Canadian Space Agency, last modified March 21, 2014, accessed March 15, 2017, http://www.asc-csa.gc.ca/eng/satellites/radarsat1/.

[5] Jezek, “RADARSAT-1 Antarctic Mapping Project.”

[6] Jezek, “RADARSAT-1 Antarctic Mapping Project.”

[7] Jezek, “RADARSAT-1 Antarctic Mapping Project.”

[8] Jezek, “RADSARSAT Antarctic Mapping Project.”

Recent Comments