Adrienne Resha was one of two recipients of the 2022 Lucy Shelton Caswell Research Award. Resha is a Ph.D. candidate in the American Studies program at the College of William & Mary. Her dissertation is about Arab and Muslim American superheroes in comic books and their derivative media. Resha’s criticism and public facing scholarship have appeared online at PanelxPanel, Popverse, Shelfdust, The Middle Spaces, and the Eisner Award-winning WWAC. The following is her report on her time spent at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum in Summer of 2022.

In my application for the Lucy Shelton Caswell Research Award, I wrote, “At present, color is one of the least discussed formal elements of comics in comics studies scholarship.” I am not the first scholar to say as much (Jan Baetens did so in 2011, Suhaan Kiran Mehta in 2020), but I will hopefully be among the last, thanks in no small part to the work that I was able to do at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum this past summer. While there, I was able to see decades’ worth of Green Lantern comics, from the Golden Age (1930s to 1950s) up until what I have termed the Blue Age (2010s to present), and through them observe how race has been produced with color inks in American comic books over time.

- Alan Scott in All-Star Comics #6 (1941) – SPEC. PN6728.1 N3 A35 No. 6

- Alan Scott in All-Star Comics #6 (1941) – SPEC. PN6728.1 N3 A35 No. 6

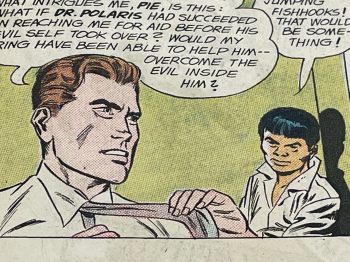

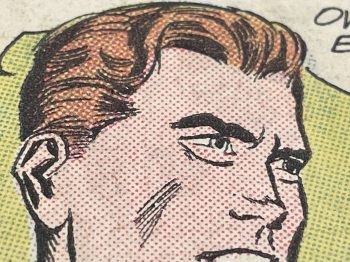

My interest in Green Lantern begins with one of the newest characters to take the name: the Arab and Muslim American Simon Baz. Baz appears to be several shades of brown throughout his 2012-13 origin story, which was colored digitally. Digitally and traditionally, comic books are and have been printed in cyan, magenta, yellow, and black (CMYK) inks. But both printing and coloring have changed dramatically since the original Green Lantern, Alan Scott, debuted in 1940. Scott’s skin tone, like many of his genre contemporaries, was (and still is) racially white: a color produced by layering yellow and magenta dots over newsprint pages. Those reddish-pink dots, as evidenced by issues of All-Star Comics at the Billy Ireland, would have been visible to contemporary readers. They remained visible, albeit decreasingly obvious as printing technology advanced, well into the Silver Age (1950s to 1970s), when Green Lantern turned from fantasy to science fiction, Hal Jordan replaced Scott, Black superheroes like Green Lantern John Stewart began to appear, and colorists’ palettes doubled.

- Hal Jordan (and Tom Kalmaku) Green Lantern #21 (1963) – SPEC PN 6728.3 N3 G7 no. 21

- Hal Jordan (and Tom Kalmaku) Green Lantern #21 (1963) – SPEC PN 6728.3 N3 G7 no. 21

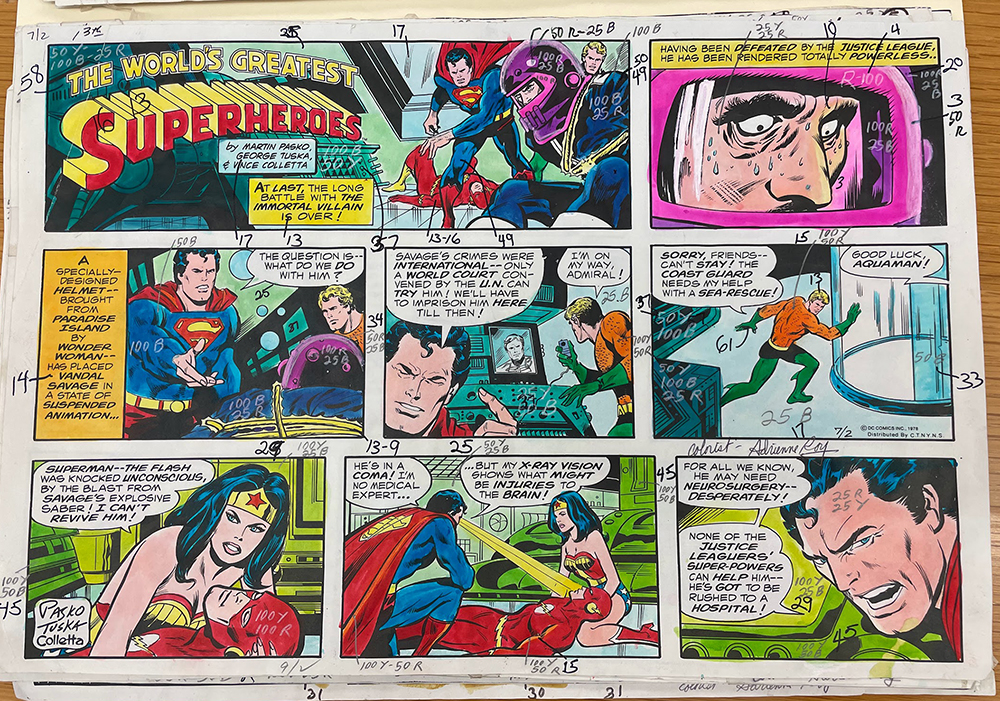

The cyan, magenta, and yellow inks that produced Stewart’s racially black, literally brown skin tone were still visible to the naked eye even after the industry turned to digital coloring in the 1980s. If not for the Lucy Shelton Caswell Research Award, however, they would not have been visible to me. Doing research for my dissertation, “From Superman to Sana Amanat: Alienation, Assimilation, and American Superhero Comics, 1938 to Present,” prior to my trip to Columbus, I had been relying on modern reproductions of older comics (which obscure the coloring, separating, and printing processes in favor of flat colors) and digital editions of newer comics (whose pixels are configured in blue, red, and green rather than cyan, magenta, and yellow). Now, in addition to having gotten to see original printings (and how they depict white, Black, Indigenous, and Latinx characters) firsthand, I also have a digital archive of pictures that I was able to take during my time in the Lucy Shelton Caswell Reading Room.

- John Stewart in Green Lantern #87 (1971) – No. 87, Michael Barrier Collection of Comic Books

- John Stewart in Green Lantern #87 (1971) – No. 87, Michael Barrier Collection of Comic Books

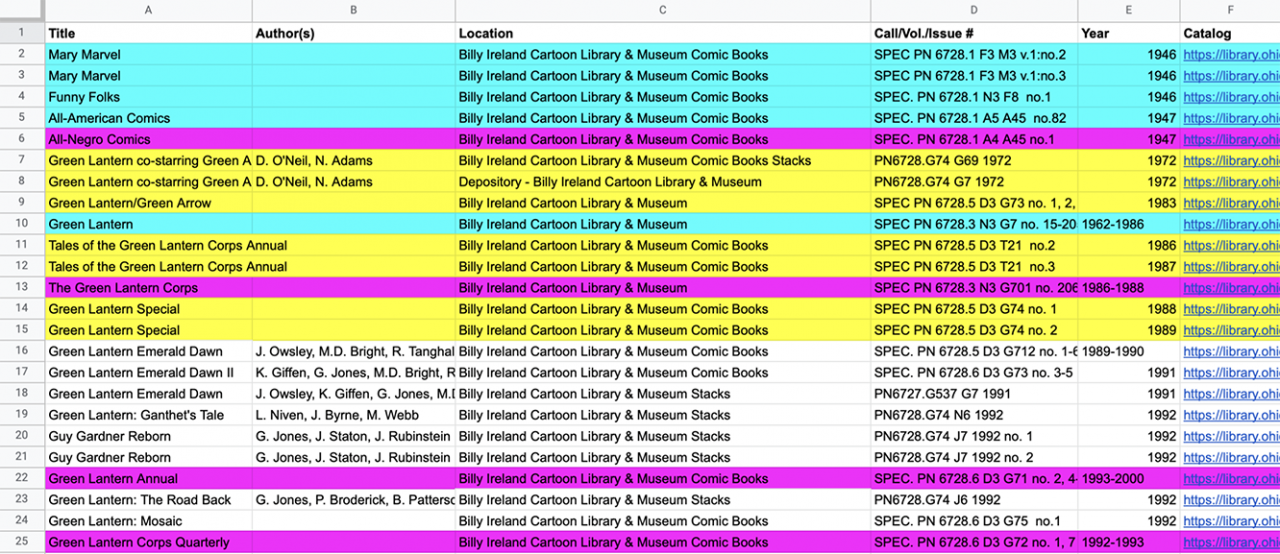

Two weeks before my visit, I submitted a materials request form. Working from the template provided by the Billy Ireland and combing their catalog online — searching “Green Lantern,” sorting chronologically, and scrolling from the last (oldest) to the first (newest) page of results — I assembled a spreadsheet that included Title, Author(s), Location (at the library), Call/Volume/Issue Number, Year of Publication, and a hyperlink (back to the catalog). I then color coded the spreadsheet by highest priority, high priority, and priority, leaving materials I would like to but did not need to see uncolored. In order to maximize the limited time that I had in the reading room, I did not actually read most of the comics that I had requested.

Instead, working chronologically as often as possible, I would copy an issue’s title, authors (when credited), call number, and publication year from my requests into another sheet, then take a picture of an interior page (usually the first one with other publication info, like cover date and country of printing). After that, I would take pictures of selected interior pages, focusing first on panels (for context, which affects how we see color) before zooming in on people. Turning my iPhone camera to a 5x zoom, my hand would hover as close as I could get it to the page without it getting blurry and snap a pic. This method meant that I got to look at about 200 single issues as well as original art (by Neal Adams and Martin Nodell), color guides (Adrienne Roy), and collected volumes (a few of which I did, at the end, get to read) in a little less than three business weeks. I left with some answers, more questions, and a lot of writing to do.

I am sincerely grateful to the Lucy Shelton Caswell Research Award Committee and to the staff of the Billy Ireland, especially Susan Liberator, for making my research trip possible.

Recent Comments