Dr. Margaret Galvan was a recipient of the 2023 Lucy Shelton Caswell Research Award. Galvan is Assistant Professor of Visual Rhetoric in the Department of English at the University of Florida. Her research examines how visual culture operates within social movements and includes her book, In Visible Archives: Queer and Feminist Visual Culture in the 1980s from University of Minnesota Press. The following is her report on her time spent at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum in 2023.

Dr. Margaret Galvan and the Lee Binswanger Collection

For more than a decade, I’ve been researching comics by LGBTQ+ creators. I’ve traveled to roughly two dozen archives in the U.S., UK, and Canada, drawn upon growing collections online, and have even begun building my own collection of rare LGBTQ+ comics. In much of my research, I’ve been accessing these comics through queer and feminist archives and getting a sense of how these cartoonists mattered within these communities. When I heard that I had received the 2023 Lucy Shelton Caswell Research Award to conduct research in the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum, I was thrilled to get an opportunity to examine LGBTQ+ cartoonists from another perspective, thinking about their relationships with the larger comics industry and connections in particular to underground and independent comics scenes.

This generous fellowship supported me in nearly two weeks’ worth of research in the collections in July 2023, which gave me a chance to dive deep and cover a wide range of materials. In recent years, there’s been an explosion of queer comics publishing and scholarship; my research focuses on how there’s still a large swath of queer comics history that remains relatively uncharted. The book project that I was researching at the Billy Ireland focuses on how LGBTQ+ cartoonists built community and innovated comics in the 1980s-1990s. With that in mind, what I want to share here are two big “light bulb” moments I had over the course of my research and think about what they can tell us about how we collect and remember LGBTQ+ cartoonists.

Over the first two days of my visit, I pored over the biographical files of roughly 80 LGBTQ+ cartoonists, which were a rich trove of information. While some files consisted of clippings about the artists compiled in-house, half of the files contained information sent by the artists themselves. Lucy Shelton Caswell started the biographical registry of cartoonists in 1991—a historic moment when most LGBTQ+ cartoonists weren’t able to participate in the wider comics industry. These cartoonists responded immediately, most of them sending their forms between late 1991 and early 1992. A majority of the responses were from lesbian cartoonists—Andrea Natalie had created the Lesbian Cartoonists’ Network the previous year and would give out the addresses of group members to publishers, editors, and other reputable individuals. All of the lesbian respondents were affiliated with the organization. The registry consisted of a double-sided form that asked cartoonists about the details of their career, serving as an invaluable snapshot of factual information. By soliciting their information for the collection, Caswell welcomed them to be included in comics history. In correspondence to Caswell archived with her biographical file, Rhonda Dicksion recognized the importance of this gesture: “Thank you for asking me to be included in your registry of cartoonists. I consider it a great honor. I’m also thankful (and amazed) that the cartoons that I produce are so popular. It’s a rare treat to be able to follow your bliss, have fun, and receive a little acclaim, too. But then, you must know about that—your job’s bound to be a lot of fun, too.” In this brief paragraph, she draws a connection between the passionate nature of her work and Caswell’s.

As much as these forms are important sources of biographical information, what interested me was how these cartoonists responded in ways that made visible how the registry’s questions were erasing the careers and lives of LGBTQ+ individuals.[i] On the front of the form, in a section entitled “major cartoon-related awards,” two artists pushed back. Rona Chadwick gently noted, “I haven’t won any yet but what I would aspire to, when they think of it, is the Feminist Cartoonist of the Year Award,” naming an imagined award that did not yet exist. By contrast, Michelle Rau was more direct: “Are you kidding? Feminist cartoons would NEVER win awards in any competition sponsored and judged by white, middle-class, heterosexual men.” Her remarks gesture towards why so many of her fellow respondents left this section blank.

On the back side, in the “Family Information” section reserved to list ostensibly heterosexual partners and children, many of the cartoonists modified the form to make their intimate lives visible, while others, even those in committed relationships, left it blank, leaving their families unrecognized in the same way they would be on so many official forms. The section asked in a seemingly straightforward manner for “Marital status (Please circle one): Single/Married/Widowed/Divorced” with further room provided to specify “Spouse’s complete name,” followed by three lines for “Children’s names” and their “Birth date[s].” Leslie Ewing asked, above her circling of “Married:” “Does joined at the hip count????” and added “long-time companion” over “spouse’s complete name,” specifying that she and Rebecca Le Dere had been together for ten years. When Howard Cruse added “Domestic Partnership” at the end of the list, he wrote a note in red felt tip pen pointing to his addition, “Should be on your standard form, folks!” In circling “Single,” Fish drew an arrow to the margin where she asked: “Can I say that I am single when I’ve had a girlfriend for 3 years now? This question is a bit antiquated.” As an addendum to her selecting “Married,” Nikki Gosch wrote “to a woman (unofficial as gay marriage is not recognized at this time). We have been committed since 7/11/1988.” (As a reminder, it would be almost two and a half decades until marriage and its privileges were extended broadly to LGBTQ+ individuals living in the U.S.)

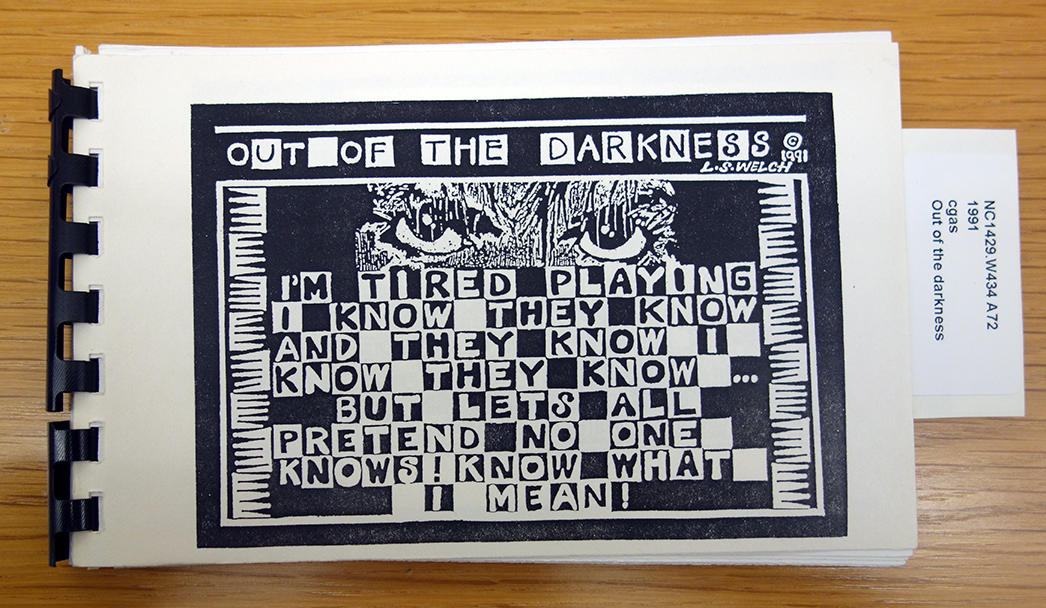

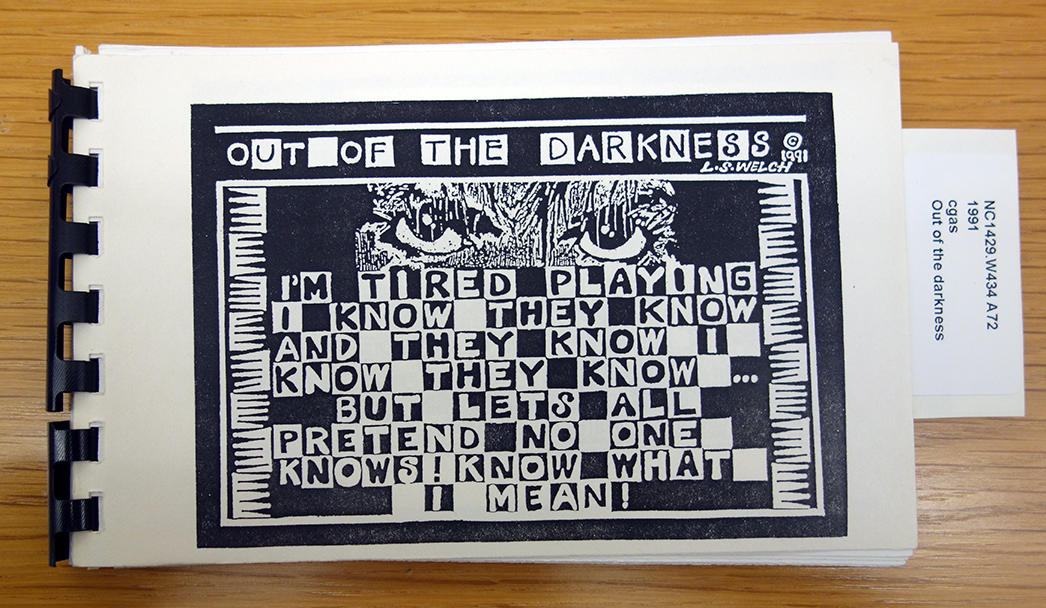

Some cartoonists also added in their cats and dogs in this section, acknowledging the different makeup of their families. Diane DiMassa amended “children’s names” to “cats’ names” and recognized the three fur children that she was raising with her long-time partner, Stacy A. Sheehan: Goalie Jane Wilson, Frank Russell Sheehan, and Iggy Henry Sheehan. Nikki Gosch named both “Peanut (tabby cat)” and “Bosco (black cat),” and added that she and her partner Deirdre Lynn Smith were “thinking seriously about becoming pregnant! Will keep you updated :)!” For her marital status, Kris Kovick listed “Queer w/ dog,” adding “Thunder Kovick” as her spouse rather than her child as her fellow cartoonists had done. For children, Amy E. Kyes wrote, “A dog named Tori!—She’s regularly featured in my cartoon strips.” A later version of the form that a couple lesbian cartoonists filled out in 1995 contained the same marital status options, showing the intractability of the form and how sticking to the official record mattered more than accurately recording these individuals’ lives for posterity. How the cartoonists actively countered the compulsory heterosexuality of these forms echoed their comics where they made their subcultural lives visible. Some of the cartoonists also sent along copies of their comics, such that the Billy Ireland contains some rare small press comics, including ones by Nicole Ferentz and Linda Sue Welch that I’ve not seen in any other collections.

Linda Sue Welch’s “Out of the Darkness” (1991)

Susan Liberator was a constant presence in the reading room who I shared my research with and who located some truly amazing finds in feminist and LGBTQ+ comics history that had not yet been fully processed or cataloged. Early in my visit, I mentioned to her that I had located some rare early LGBTQ+ comics that were tagged as a gift of Avis Lang and others that were marked as part of the Lee Binswanger Collection—both women I knew for their involvement in feminist comics and community building. I asked her if there was, potentially, more information beyond these cataloged comics. Liberator was able to locate the affiliated unprocessed collections and brought them out for me to look at. The Avis Lang Collection consisted of several banker’s boxes of research that Lang did when she was preparing Pork Roasts, her early feminist comics exhibit that opened at UBC Fine Arts Gallery, Vancouver in 1981, that she published in comics form, and that later traveled to the Billy Ireland. With its focus on 1970s feminist comics, the collection was outside the scope of my current project, but it is an invaluable time capsule of a history that’s still not fully told.

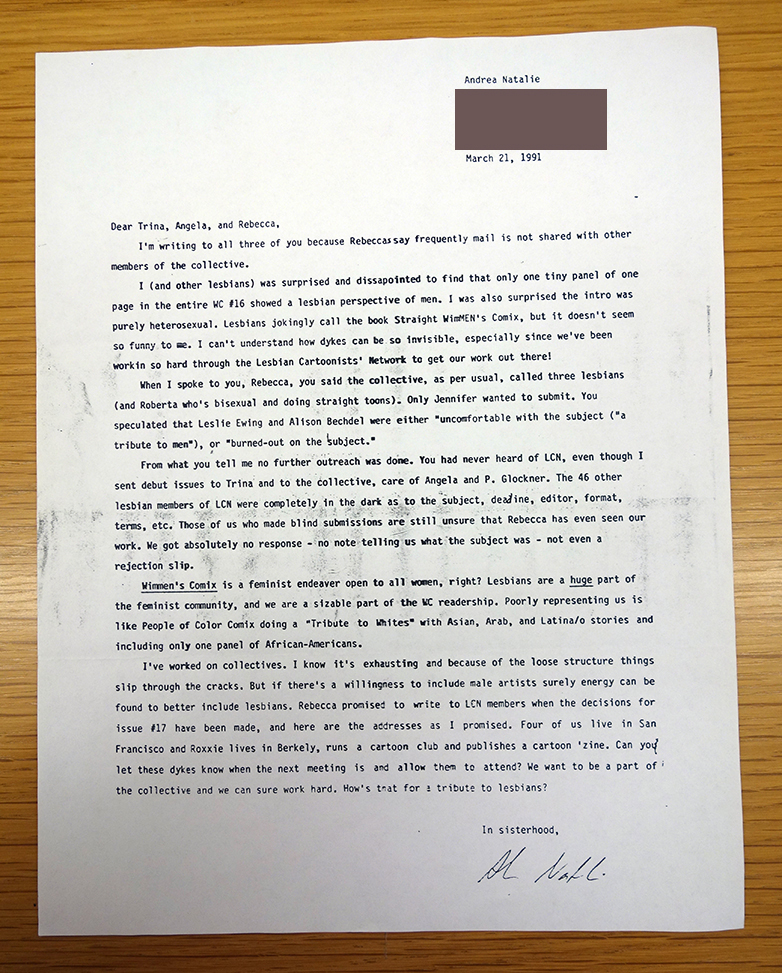

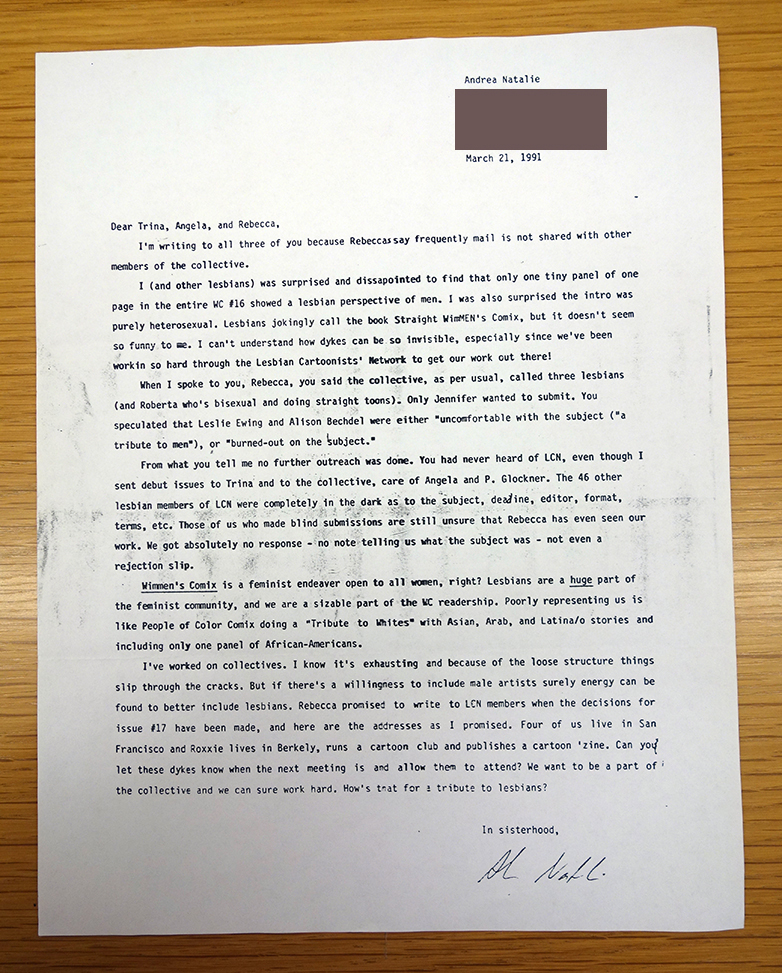

The Lee Binswanger Collection consisted of one slim archival box that arrived at the Billy Ireland in 2000. Aside from librarians removing and cataloging five comics that were included in the collection, the rest of the files have been sitting unprocessed and unread over those two decades.[ii] Binswanger is a feminist cartoonist who actively published in Wimmen’s Comix starting in the 1980s, publishing in issues #8-17 (1983-1992) and editing Wimmen’s Comix #8 (1983) with Kathryn LeMieux and Wimmen’s Comix #13 (1988) with Caryn Leschen. Her collection consisted of comics and correspondence that women involved with Wimmen’s Comix received in its final years for issues #16 (1990) and #17 (1992), though women continued to send along comics in the hopes of an eighteenth issue that never materialized. I spent a day and a half poring through the files and photographing nearly everything. Roughly 60 women wrote in—a third of the correspondents were lesbian cartoonists. As I already knew from reading the Lesbian Cartoonists’ Network newsletter, lesbian cartoonists were displeased with the heterosexuality of Wimmen’s Comix #16 (1990) and its themed focus on men. LCN editor Andrea Natalie encouraged her fellow cartoonists to send their work for consideration in the following issue. Their letters, which included comics, clippings, and resumes, provide vital information about these cartoonists, whose contributions are still undervalued to this day. Like the bio files, this correspondence offers essential context to learning more about these artists and shows how these artists had to work hard to advocate for themselves in a largely straight profession. Ultimately, five lesbian cartoonists affiliated with LCN, Natalie included, were featured in Wimmen’s Comix #17 (1992), but the Binswanger collection makes evident the exponentially larger world of feminist and lesbian cartoonists that was emerging at the same time that Wimmen’s Comix was unfortunately coming to a close. Sitting with this collection reminded me just how much history has not been told about this period and just how many artists remain forgotten.

1991 letter from cartoonist from Andrea Natalie complaining about the heterosexism of Wimmen’s Comix #16 (1990) that was part of the drive to have more lesbian representation in the series.

Endnotes added by the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum:

[i] The biographical registry form was discontinued from use at BICLM in the early 2000s.

[ii] Although this collection had been inventoried, a record for it was not yet online. It has since been added to the BICLM online collections and is available here.

Recent Comments