When our dear friend and colleague in comics scholarship, Carol Tilley, discovered a fascinating fragment from the days of the comics code in The Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum archives, we didn’t think we could be happier! She topped that, however, when she offered to write a post for our blog about this fantastic piece of satire history…

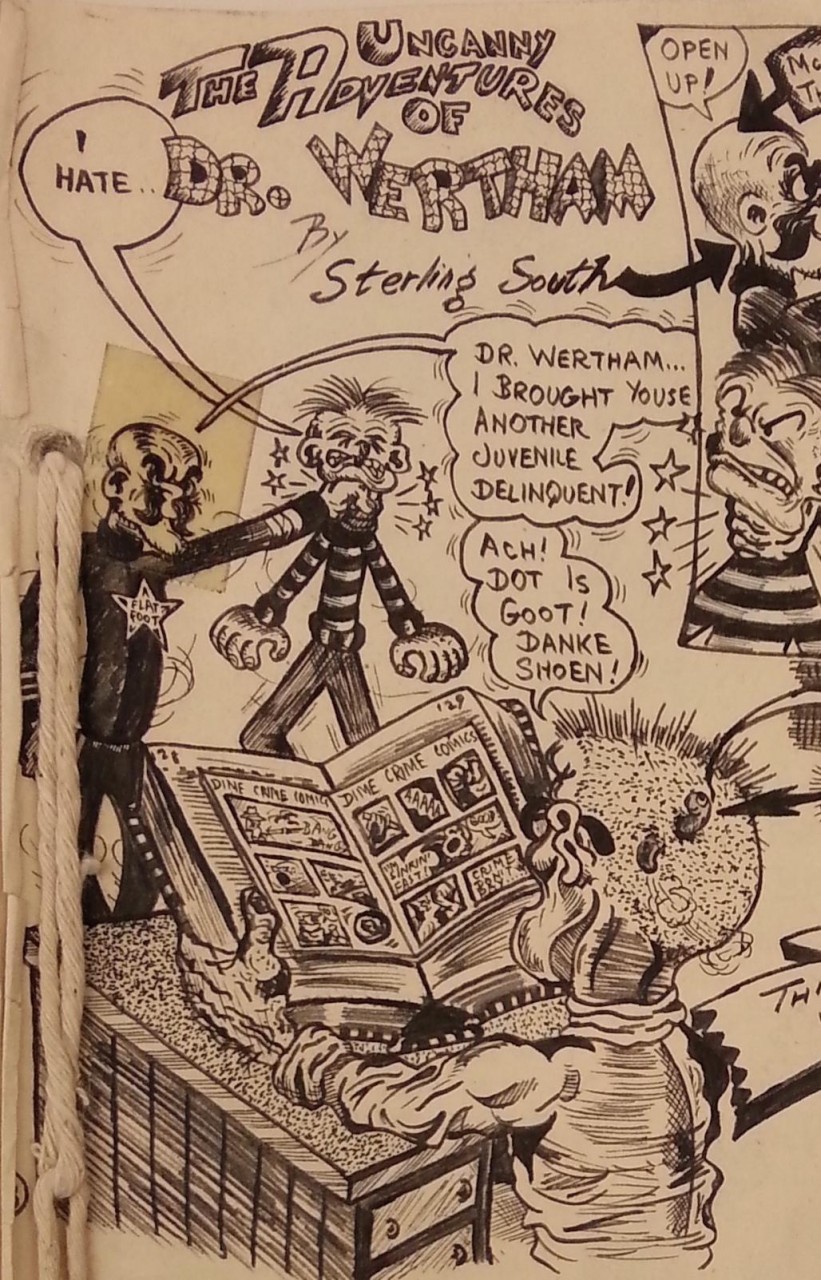

“The Uncanny Adventures of (I Hate) Dr. Wertham”

by Carol Tilley

In the ebb and flow of anti-comics sentiment, 1948 was a sui generis year. Sure, 1954 had the publication of psychiatrist Fredric Wertham’s hyperbolic Seduction of the Innocent, the US Senate’s Judiciary Subcommittee hearing on the role of comics in promoting juvenile delinquency, and the birth of the Comics Code Authority. But 1954 was a denouement to 1948’s frenzied pace: ordinances restricting sales of comics in more than 50 US cities; condemnation of comics from groups such as the National Congress of Parents and Teachers and the Fraternal Order of Police; creation of the Association of Comics Magazines Publishers (AMCP) and its toothless set of editorial guidelines that most publishers ignored. And those are only some of the highlights.

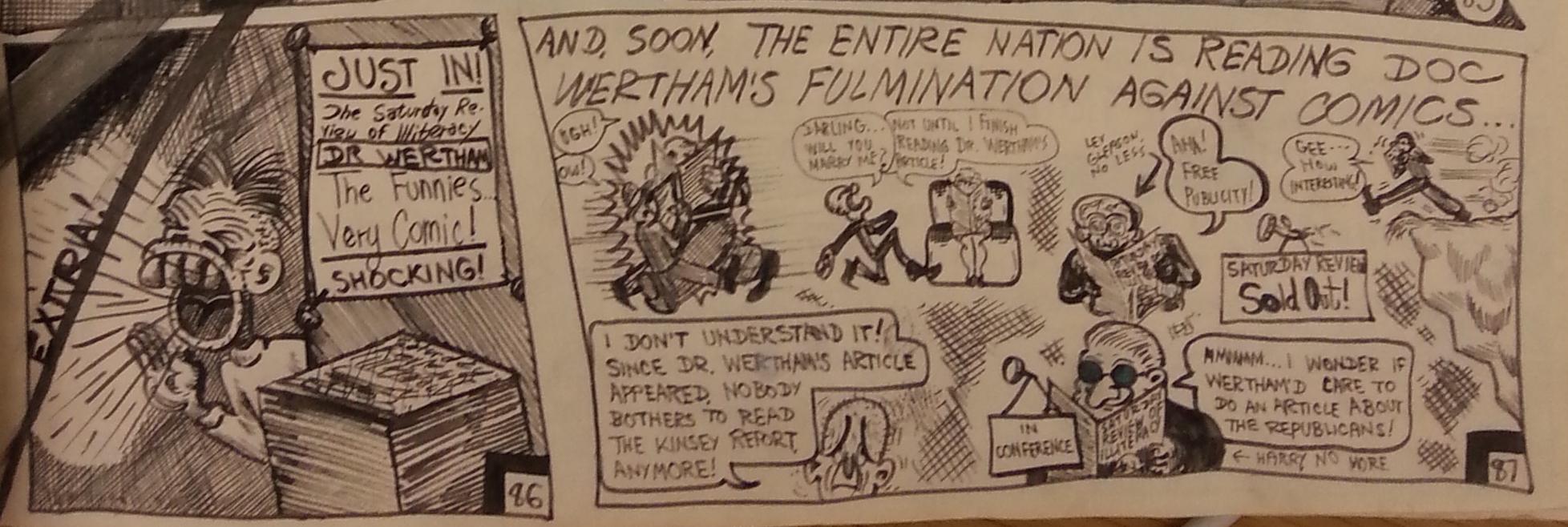

Wertham with his message connecting crime comics with illiteracy, delinquency, and other ills was undeniably one of the centerpieces of the year that was 1948. Launched onto the national stage in December of the preceding year, Wertham ubiquitously denounced comics at lectures and in publication. For instance, he organized a lively symposium on comics as part of the monthly meeting of the Association for the Advancement of Psychotherapy, where several presenters laid out their rationales against comics. In the open discussion that followed, he did little to reign in Gershon Legman—a folklorist and critic who delivered one of the evening’s papers—during an attempt by comics publisher Charles Biro to give a counterpoint. And in May of that year, Wertham published an outline of his eventual argument for Seduction of the Innocent as an article titled, “The Comics…Very Funny!” in Saturday Review of Literature. That publication’s drama critic John Mason Brown had deemed comics to be the “marijuana of the nursery” in a radio conversation with cartoonist Al Capp and others just two months earlier.

Watching these events unfurl from the sidelines was a cartoonist with a style that’s reminiscent of an unholy lovechild spawned from Basil Wolverton and Robert Crumb. He channeled his observations into a satirical, trenchant, and silly 27-page comic book, The Uncanny Adventures of (I Hate) Dr. Wertham. This pen-and-ink comic is drawn on standard office paper and bound with cotton string, its pages slightly ragged from age and dotted with bits of yellowing tape. The author bills himself as Sterling South, a play on the writer and critic Sterling North, who helped inaugurate mid-century comics hysteria with a widely circulated and emulated 1940 editorial in the Chicago Daily News. Tucked into a folder with a few bulletins published between the years 1946 and 1948 from the National Cartoonists Society, the comic has languished, seemingly forgotten—it was noted on the finding aid, but one has to be looking for it—in the storage of the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum until I stumbled on it last October during a research visit.

Here’s the story the comic tells.

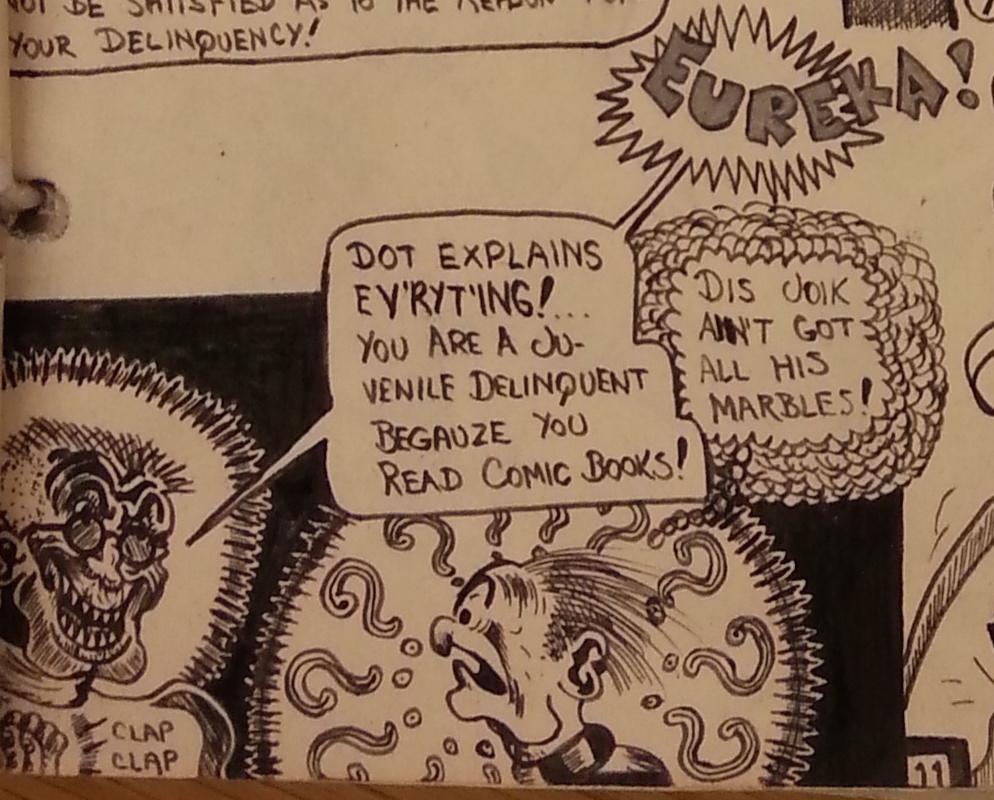

A police officer brings a juvenile delinquent to see Wertham, who agrees to psychoanalyze him. The first question Wertham asks the boy is whether or not he reads comics, and the boy responds, “Sure! Don’t everybody???” Wertham immediately seizes upon a connection between comics reading and juvenile delinquency, and the boy, realizing the possibilities in misleading the doctor, plays along. Wertham assiduously studies a funny animal comic the boy gives him, determined to prove the comics—delinquency connection. Ultimately Wertham pardons the boy, telling him that it is “the comic book publishers…and not you who should be punished!” Wertham gathers more comics for study and sets on his course to document the ill-effects of reading them.

During his study, Wertham listens to a radio forum about comics that features critic John Jason Frown, cartoonist Al Sapp, and others. During the question and answer period, Charles Biro is hauled out of the audience by “the little men in the white coats.” Feeling he’s found a kindred soul in Frown, Wertham takes his completed manuscript to him and Frown agrees to publish it in the Saturday Review of Illiteracy. Soon “the entire nation is reading Doc Wertham’s fulmination against the comics” and local municipalities enact ordinances against comics.

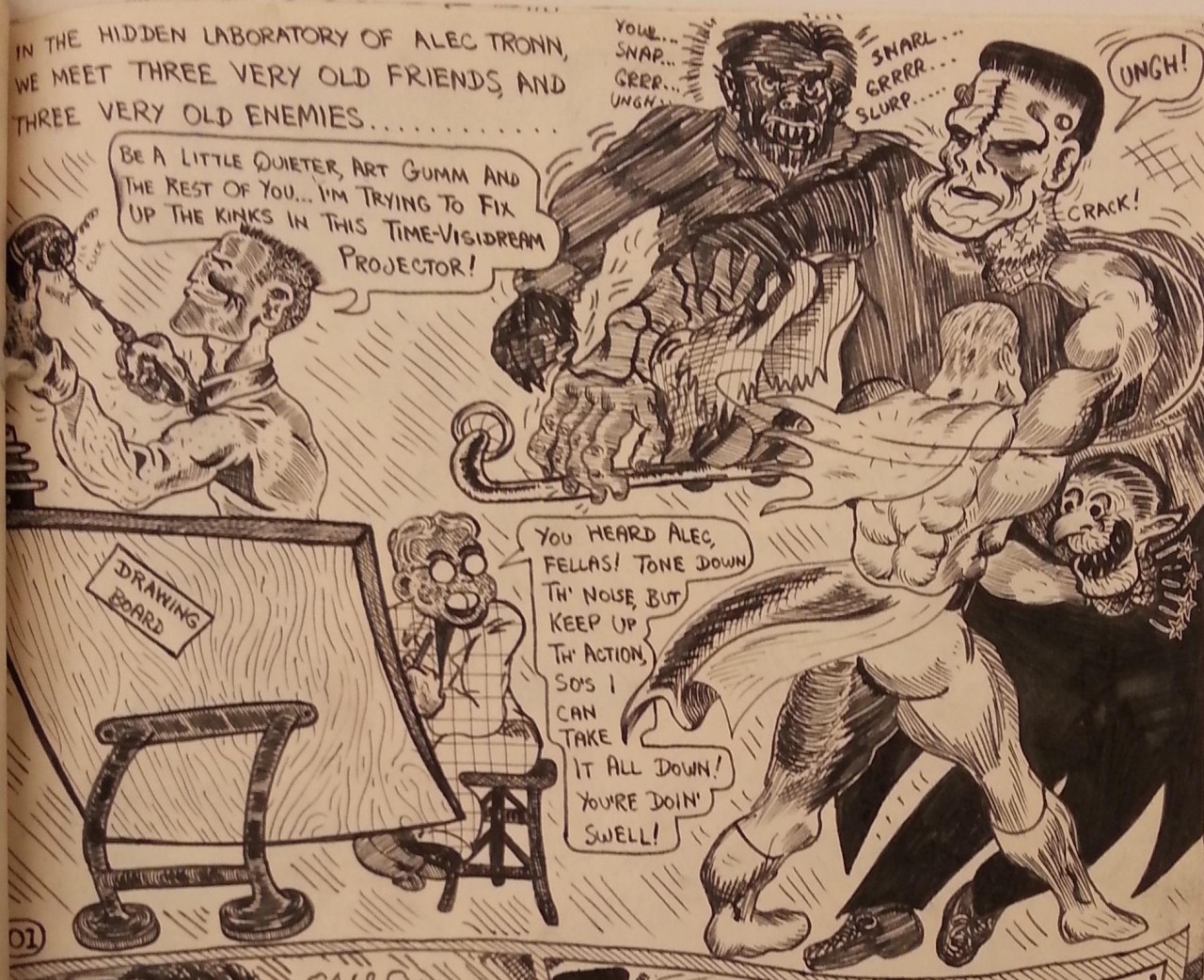

Cut to the studio of a couple of comics creators and their creations, which include a monster trio and a standard superhero, Major Muscle. The group hatches a plan to counter Wertham’s message, which has begun to reduce sales. In short order, the characters take a time travel device to Wertham’s house. There they are able to send him on a memory trip to his childhood in Germany, where he recalls that he may have done some naughty things even though he grew up in a comics-free environment.

Once awake and no longer under the effects of the time travel device, Wertham realizes the error of his anti-comics argument. He endeavors to retract it, but in doing so, he is professionally disgraced and left penniless. The comic ends with Wertham trading in the last of his worldly possessions for a revolver, which he uses to kills himself on a pier.

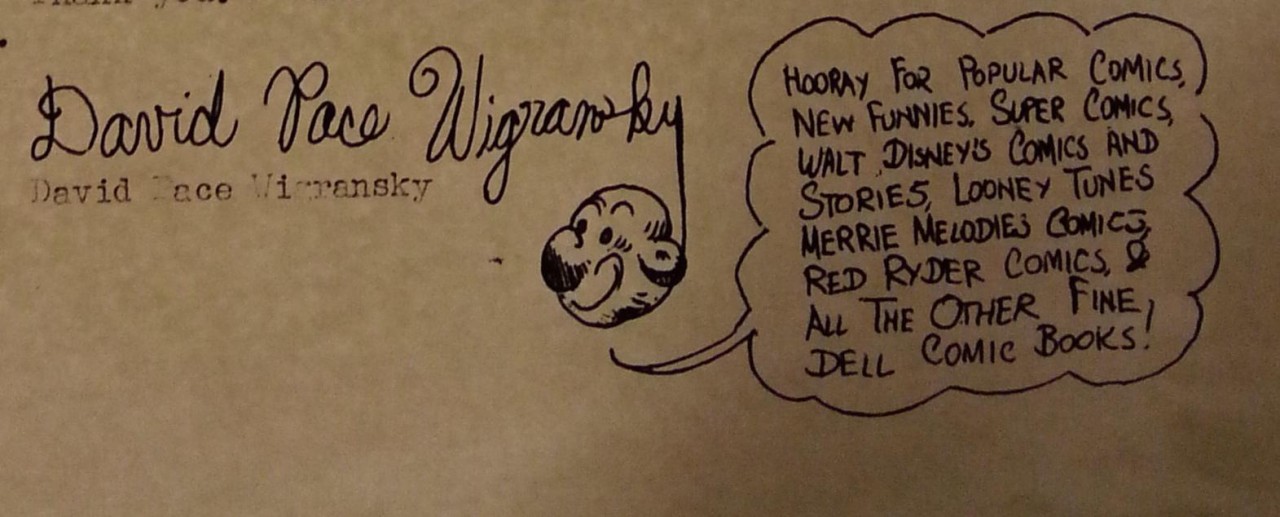

Throughout the comic, the unidentified cartoonist deftly incorporates references to key events, locations, and figures beyond those I noted in the summary. Wertham’s groundbreaking Lafargue Clinic in Harlem makes an appearance; in the comic, it’s motto is, “Behind every crook…..there’s a comic book!” The AMCP and its code are namechecked. There’s a shout-out to contemporary provocateur Alfred Kinsey. And then, on page 22 there’s a nameless, crew-cut teenager in a plaid shirt who owns 5,919 comic books, but there’s only one person it could be: David Pace Wigransky.

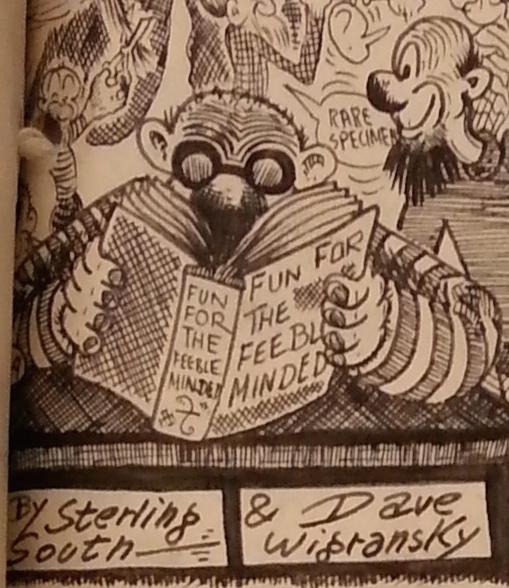

David Pace Wigransky was the 14-year old comics enthusiast who wrote a letter of rebuttal to Wertham’s Saturday Review of Literature article, illustrated with a photo of himself amid a pile of comics, wearing a plaid shirt and sporting a crew-cut. On the following page of the Wertham comic, Wigransky reveals himself as the cartoonist behind this tour-de-force comic book. It’s a subtle nod: he signs his name—Dave Wigransky—alongside that of the fictional Sterling South. In print, he was ‘David Pace Wigransky,’ but on the pages of The Uncanny Adventures of (I Hate) Dr. Wertham, he’s simply ‘Dave Wigransky.

Wigransky clearly wanted to be perceived as knowledgeable among comics folks. In addition to his erudite letter in the Saturday Review, he wrote twice to Milton Caniff, both were two-page letters—impeccably typed—one in 1948 and another in 1949. It appears that the first was a response to a letter from Caniff thanking him for the Saturday Review letter, while the second served both as a critique of a traveling exhibit of cartoon art as well as a request for an original Steve Canyon Sunday page. In the summer of 1948, he also wrote to George Delacorte, President of Dell Publishing, announcing his intention to “write a book on the history of American Comic Magazines during the first half of the twentieth century” as soon as he graduated from high school in 1951. It seems David never wrote that book, although in the 1960s he compiled a definitive discography for Al Jolson and wrote an illustrated novel on teenage delinquency. An acquaintance who posted about him on a Jolson message board described him as both “fascinating” and “difficult,” but I would expect little else of someone precocious enough to unfurl The Uncanny Adventures at age 14 or 15. David died in 1969. I would have loved the opportunity to spend a few hours with him.

Nearly seventy years have passed since Wertham launched his attack on comics and a young ‘Dave’ Wigransky lambasted our cultural follies. It’s not clear how his comic ended up in the papers of the National Cartoonists Society, but I suspect he sent it to Caniff, who was President of that organization during the late-1940s. I wonder who might have read it, what they thought, and if Wigransky was disappointed not to have his copy—probably the only one—returned. As it stands, my own research published in 2012 suggests that Wigransky was indeed correct to assert Wertham’s disgrace, as the psychiatrist concocted and distorted at least a portion of his findings. I bear no ill toward Wertham the person and don’t believe that his absence would have prevented the Senate hearings or the Comics Code Authority. Still, I also suspect there are some comics fans who might wish for the ending that the teenage Wigransky envisioned for Wertham all those years ago.

Further Reading:

Tilley, Carol L. (2012). Seducing the innocent: Fredric Wertham and the falsifications that helped condemn comics. Information & Culture: A Journal of History, 47(4), 383-413.

Tilley, Carol L. (2015). Children and the Comics: Young Readers Take on the Critics. In J. Danky, J. Baughman, and J. Ratner-Rosenhaugen (Eds.), Protest on the Page: Essays on Print and the Culture of Dissent, pp. 161-179. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Wright, Bradford W. (2001). Comic Book Nation: The Transformation of American Youth Culture. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

About the author: Carol L. Tilley is Associate Professor in the Graduate School of Library and Information Science at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. Part of her scholarship focuses on the intersection of young people, comics, and libraries, particularly in the United States during the mid-twentieth century. An in-demand speaker on comics history, you can find her on the web at www.caroltilley.net and on Twitter at @anuncivilphd and/or @comicscrusader.

February 23, 2016 at 11:58 am

Very cool discovery, Carol! Do you have a rough guess as to the dating on this comic? The folder where you found it contained NCS items from 46-48: do you think it is from as early as 1948?

February 23, 2016 at 11:59 am

Hi, I loved your article(s) in Alter Ego. For a piece about Stan Lee for Roy (to be used as information for his new book on Stan Lee and eventually as an article in AE) I ordered all of the Stan Lee related correspondence in the Toni Mendez files. Those included a personal file by Ms. Mendez assistant from 1954 with all sorts of information about Dell’s efforts to stand outside of the code. My guess is eitehr that secretary or Ms. Mendez herself was at one point secretary to some sort of group that assisted Dell. Anyway, lots of policy papers, press statements and newspaper clippings all related to the code you may not have seen yet. I offered them to Ken Quattro to have a look at, but you are the appropriate person for it, I guess. Should I get the file number for you?

February 23, 2016 at 12:07 pm

Hi Jared – I do think it’s from 1948, probably summer or fall, but I don’t have a good way of actually nailing it down for now.

February 23, 2016 at 12:08 pm

Hi Ger – Thanks! I had a chance to look through most of the relevant Mendez papers. There were some cool things there and in other collections re: Dell and the events leading up to the Code.

February 23, 2016 at 1:39 pm

The Toni Mendez papers are a goldmne. I fopund plenty of stuff in there concerning Stan Lee. If you hear of anyone else sniffing around in them, I’d love to know since it will be some time before Roy published my article. I also hope one day to do Al Jaffee, Arnold Roth, Johnny Hart, and David Gantz (among others).

February 23, 2016 at 1:58 pm

Thanks for this report on an interesting find.

February 26, 2016 at 11:39 am

Learning more about David Pace Wigransky was gratifying and even more so illuminating regarding this (then) young man’s heroic defenses of the comics then under attack. I have a full file of DPW’s Sat Review of Lit back & forth inside that journal’s Letter’s section. Most could not believe he was just 14 years old.

The late Gabriel Laderman knew Wigransky. Some where here I have a file of notes I took at Gabe’s NYC apt as he waxed on about this guy. I also xeroxed some of the articles & such in the stuff Bill Blackbeard got from Maggie & Don Thompson. Might be time to relocate so much of the comics research stuff I have which was put on hiatus whilst coming to grips trying to get Katy healed from her living nightmare still unfolding.