Dr. H. Shindle Wingert was a man ahead of his time: A firm believer in preventive medicine, hand-washing and what now would be called “social distancing” to thwart the spread of disease, he served OSU more than a century ago during the 1918 pandemic.

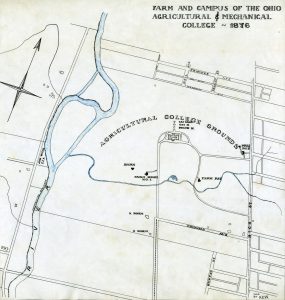

A 1903 graduate of the Maryland Medical College, Dr. Wingert arrived at Ohio State in 1907, joining the faculty as a professor in the Department of Physical Education. At that time he also was named Director of Physical Education and Director of Athletics. In 1915 the Board of Trustees selected him to be the first director of a new department, Student Health Services, located in Hayes Hall. He reported directly to then-President William Oxley Thompson.

Even before he was in charge of students’ collective well-being, Dr. Wingert was promoting good health practices. In 1908 he wrote a letter to then-Ohio State President William Oxley Thompson sharing slogans such as “Health First” and “Prevention is Greater than Cure.” Soon after he became head of Student Health Services, he proposed a student health board composed initially of student aides in the Department of Physical Education who would fan out throughout the University District, checking on ill students daily in their apartments and boarding houses and reporting their status to Dr. Wingert.

“It is necessary that all contagious diseases be reported to Dr. Wingert immediately,” the Lantern reported, “for the only safeguard to the students is the safe isolation of the patient.” It’s unclear whether the proposal was ever put into practice, however.

By 1918 the pandemic known as the “Spanish Flu,” reached the U.S. when soldiers carried it home after serving in the trenches of World War I. In September 1918, the campus began hosting the Student Army Training Corps, which brought military personnel to campus to train new cadets for the war effort. At first, Wingert was cautious, saying that there was “no necessity for a quarantine being established” even though other campuses were launching such measures. His advice, according to The Lantern, was for the men in training to keep themselves in good condition “to avoid the possibility of disease making headway among the students” and for everyone to “[c]over up each cough and sneeze, if you don’t, you’ll spread disease.”

He even made sure football games could continue, saying there was no reason to cancel them as long as spectators remained apart while in the stands. Ohio State hosted games in Columbus on October 5 and 12 against Ohio Wesleyan and Denison, respectively. The disease spread rapidly across the country, however, so as a precautionary measure, University officials ordered campus to close on October 11 and directed all students to return to their homes until the University reopened on November 12. Football games also were cancelled during that period.

Though he encouraged students to remain vigilant and avoid social gatherings if possible, Dr. Wingert announced in February 1920 that the pandemic was on the decline, with only five cases reported since the beginning of that year. In 1923 Dr. Wingert told The Lantern that “the influenza epidemic is practically ended” with only an average number of students with flu symptoms seeking treatment. During the epidemic, eight deaths were reported out of the 440 cases handled on campus.

Happy about hand-washing

After the epidemic, Dr. Wingert continued to promote good hygiene practices, such as hand-washing. In fact, he claimed that he washed his hands “100 to 160 times a day” due to “his belief that more diseases are transmitted by the hands than any other medium.” While it allowed him to maintain good hygiene, he did fear that, “they will wear out some day.”

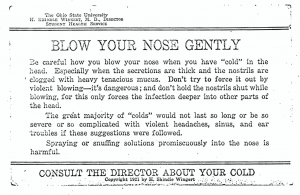

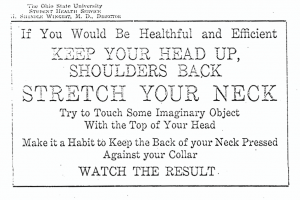

He promoted good hygiene practices in other ways. In March 1922 he created a series of 18 cards with various health tips and advice, such as “Prevention is Greater than Cure” and “Something You Should Know About Contagious Diseases.” These were made available at various campus locations, and they would be used throughout the years, such as during a mumps outbreak on campus in April 1928.

Pharmacy poisonings scandal

Despite the success of preventing a large-scale outbreak of the flu at Ohio State and the creation of the helpful health cards, Dr. Wingert’s tenure as health services director was tainted by controversy. In 1925 two students who had fulfilled prescriptions at the campus pharmacy died. The dispensary, which Wingert had founded in 1921, was busy during the cold and flu season and it employed many students, who often filled the prescriptions with no direct supervision. It was believed that these contributing factors allowed someone, intentionally or mistakenly, to mix deadly strychnine pills into a batch of quinine pills.

An ensuing investigation eventually revealed that the incorrect fillings may have been done by a dispensing pharmacy that provided the medications to the Student Health Services pharmacy, not the pharmacy itself. However, it was illegal for students fill prescriptions without a professional pharmacist on duty, so the pharmacy was shut down during investigation.

The strain on Dr. Wingert from the scandal may have been too much; in August 1926 he sustained a “nervous breakdown,” according to a 1970 history of the student health services, and he was placed on a year-long leave, during which his assistant director, Dr. Richard Kimpton served as acting director. Dr. Wingert returned as director in March 1928.

His own health decline

A few months later, Dr. Wingert attended a meeting on May 1 regarding the “freshman problem.” The meeting was convened by then-President George Rightmire to discuss a report that had been issued by a university-wide Committee on the Freshman Problem that had been studying how the University could help freshmen better transition to University life. Recommendations ranged from changes in the level of coursework that would be available to freshmen, to special class offerings, such as learning effective study habits. (One of the recommendations ultimately resulted in what is now known as Orientation.)

Part of that committee’s charge was to study a possible reorganization of the student health services, including putting it under the oversight of the College of Medicine. Dr. Wingert was not in attendance, however; he died due to complications from acute nephritis at the age of 61 on May 11, only ten weeks after returning as director.

Recent Comments