While formal socials and dances aren’t a part of University life anymore, they were quite popular during the early 20th Century as a way to meet people and relax. Formal dances, such as many of the military balls held from the 1900s to the 1950s, were also a socially acceptable way to date.

The formal Spring Dance was a campus wide social, where black tie suits and formal gowns were dusted off each spring for a festive gala. Here, Wesley Leas dances with an unnamed partner, stopping to smile for the camera. Wesley, or ‘Wes’ as he preferred to be called, was the president of the senior class two years later in 1938, as well as being The Best Damn Band in The Land’s drum major. An engineering major, Wes also managed to find the spare time to involve himself in a number of campus organizations and social clubs, such as the American Institute of Electrical Engineers, the Ohio Staters Inc., the Quadrangle Jesters, and the fraternities of Kappa Kappa Psi and Sigma Chi. In spite of this busy schedule, Wes still found time to focus on his studies and find a date to the Spring Dance formal!

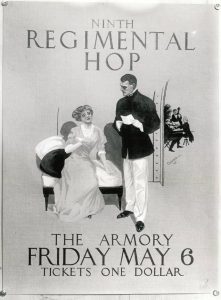

The “Regimental Hop” was a formal military dance held semi-annually at OSU, often a freshman’s first formal dance. The dances were put on by the regiment’s officers, and typically held at the Armory on campus. The first Regimental Hop was held on May 18th, 1906, and by 1910, the dances had become a regular feature of the social calendar. The Regimental Hop was relatively popular, often with 200 or more students buying tickets to attend despite the cost of admission – a $1 ticket in 1910 is about $25 in 2020!

The annual military ball was another popular formal held at Ohio State, which anyone could attend, provided they purchased a ticket from one of the students in advanced military training. Attendance was limited to 1,000, and the tickets were $3.50 for each couple, roughly $62 in 2020! Part of the high cost of attendance for the 1938 dance may have been used to cover the cost of the musicians – $2,000, which The Ohio State Lantern reports was “more than any band has received in the history of the University”. Paying the equivalent of almost $36,000 in today’s money to hire the band is unsurprising, however, considering Hal Kemp’s popularity. The musician had become a popular jazz saxophonist, recording for songs such as “You’re the Top” and “Lullaby of Broadway”, which was a hit in 1935. The military ball was one of the last professional engagements he and his band would play, due to a fatal car crash two years later in 1940.

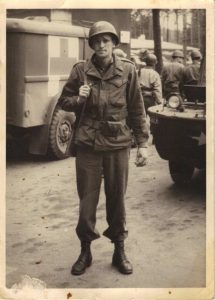

As World War II finally ended in September, 1945, many military “sociables” naturally shifted to the veterans of the war who were finally returning home after years of fighting in Europe and the South Pacific. Veteran’s groups and associations became a fixture of campus life, and one such group decided to form a dance band, holding a contest in April during the All Veterans’ Campus Mixer to determine the name. The 16 piece ensemble, led by Harry Chorpenning, became known as the “All Ohioans” thanks to William Wilson’s winning entry, and included a female vocalist who accompanied some of the pieces.

Dances didn’t always center around military officers or campus-wide events, however – some were smaller, more intimate affairs that included members of a sorority or fraternity, members of campus clubs or organizations, or even social groups, such as the Mansfield Club. To be a member of the Mansfield Club, all a student had to do was prove they were from Mansfield, Ohio. The boundaries were later extended to include all of Richland County, in an effort to boost membership. This particular photo was taken during the 1948 February “Winter Whirl” dance, during winter quarter, which included a homey, small town feel in the decorations. Couples danced to Bus Brown’s trio of musicians and refreshed themselves at the bar with bottles of Coca-Cola. The dance ended at midnight, with the song “Home Sweet Home” playing.

Despite the popularity of dances in the first half of the 20th century, university sponsored dances have since fallen out of favor.

Written by Beth Crowner.

Recent Comments