(In celebration of the University Archives’ upcoming 50th Anniversary in 2015, we bring you “The Twelve Days of Buckeyes.” This is day 10 in a series of 12 blog posts highlighting the people who were instrumental in the creation and growth of the Archives.)

There is nothing more synonymous with being a Buckeye than the colors Scarlet and Gray. And the person Buckeyes can thank for preserving the earliest beginnings of those OSU colors is John Kleberg.

First, a little background on Kleberg: He came to OSU in 1973 as associate director of Public Safety, taking charge of the operations side of the Campus Police unit. In 1981, he was appointed as director of the University’s internal audit unit in the Office of Business and Finance.

Although his background is in law enforcement, he has been heavily involved in preserving OSU history since his retirement in 2000 as assistant vice president of Business and Finance. (He returned in 2001 as Special Assistant to the Vice President of Student Affairs.) For instance, he’s served on the committee that coordinated the program to record, preserve and restore works of art on campus. He’s also spent much of his university-related time after retirement in raising money and awareness for the historic Cooke Castle on Gibraltar Island in Put-in-Bay.

Cooke Castle was built by Jay Cooke, the Civil War financier who bought Gibraltar Island in 1864. There, the family entertained such dignitaries as Supreme Court Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase, President Rutherford B. Hayes and General William Tecumseh Sherman. In 1925, Cooke’s daughter, Laura Barney, sold Gibraltar Island to then-OSU Board of Trustees member, Julius Stone, who immediately donated the property to the University to house a lake research facility that would become Stone Lab.

Kleberg has worked tirelessly to restore the historic Cooke Castle, and in fact, with his help, the first floor of the Castle, which had been closed for a number of years, is now open to the public at certain times. The Archives also has benefited from Kleberg’s interest in Cooke Castle; three years ago, he gave us a number of materials he’d gathered on Jay Cooke.

Kleberg has given a myriad of items to the Archives over the years. They often represent the more mundane history of a large educational institution – an old class microscope he picked up at a University surplus auction or two police badges from the Department of Public Safety.

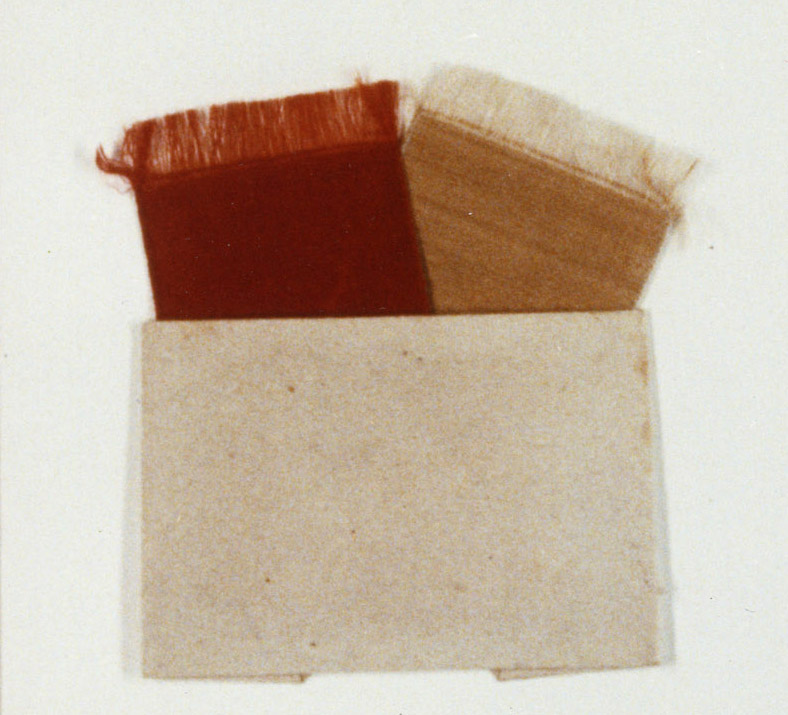

Then, there was the truly one-of-a-kind historical artifact he donated that makes him a standout among donors: the original scarlet-and-gray ribbons that adorned the diplomas of the first graduating class in 1878.

When it was almost time for Commencement that year, the class assigned a committee of three to pick out a pair of sample ribbons to determine which color of ribbons would be tied around the diplomas. The original pair of scarlet-and-gray ribbons they chose were cut into three parts, and a section was given to each committee member as a memento. Years later, one of the members – Curtis Howard – found his and presented them to the University in a frame with a letter attached to the back explaining their significance. They were hung in Sullivant Hall, but as sometimes unfortunately happens, the framed ribbons went missing at one point.

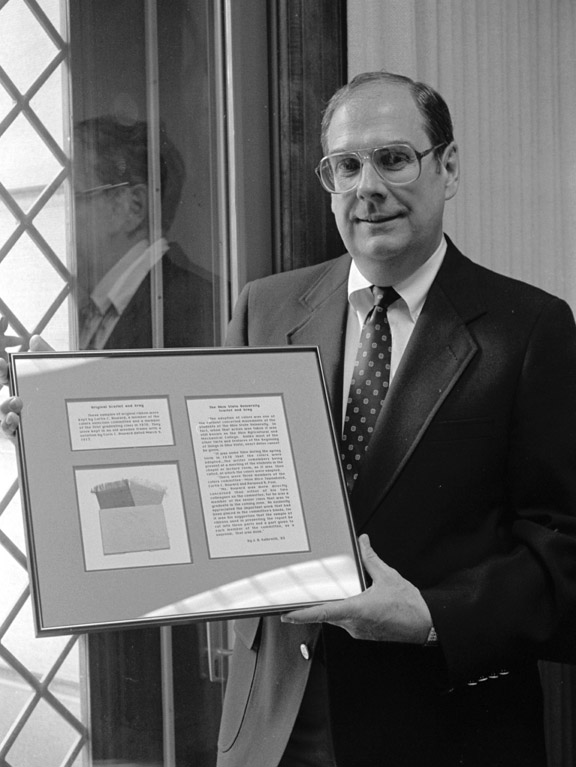

In the late 1980s, a gentleman identifying himself only as an attorney representing an estate in Florida, showed up in Kleberg’s office with the ribbons and some documentation. Kleberg did some subsequent research and determined they were most probably part of the original ribbons. And then, he made sure they made it to the Archives.

Without his dedication to preserving OSU history, those ribbons may have ended up in Kleberg’s wastepaper basket, and Buckeyes would not have these priceless reminders of how we became so devoted to Scarlet and Gray. So for all his contributions to OSU, we give him a hearty thanks from the Archives!

Recent Comments