The following is Part II of a two-part essay that was published on the Spotlights blog of the The North American Coordinating Council on Japanese Library Resources (NCC) in October 2022. The essay was co-written by Jeremy Joseph (OSU Class of 2024) and Japanese Studies Librarian, Dr. Ann Marie Davis. Part I of this essay is available here.

Capturing the Mundane to the Extraordinary: Tobita’s Valuable Sketches

A trove of details, from the mundane to the extraordinary, about life at Sugamo naturally surfaced as a result of this Project. For example, extensive interviews with Tobita revealed that he began gifting his art to fellow inmates at the behest of Prince Nashimoto Morimasa, an uncle-in-law of Emperor Shōwa and Tobita’s fellow inmate and confidant at Sugamo. When Prince Nashimoto was released in April 1946, he asked Tobita to offer him one of his drawings as a parting gift.

Figure 5. In “Inmates Sleeping in a Cell,” Tokio Tobita depicts convicts suffering haunting nightmares as well as a cacophony of late-night prison sounds. The emblem “American Red Cross” is visible on the backside of a presumably rationed and donated leaf of paper. Pencil on paper, 13.8 × 21.5 cm. Fumio Fujiki and Tokio Tobita collection, The Ohio State University, Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum; SPEC.CGA.SUG.2012.

Tobita had drawn pictures for himself in private, but he had never shared his work before the prince’s request. After some thought, he drafted a cartoon-like watercolor, entitled Senpan haishoku no zu (roughly translated, “An Illustration of the Cafeteria Line for War Criminals”) in which about two dozen Class-A and Class-C suspects, including Hideki Tojo, Prince Nashimoto, and Tobita himself, stand in single file as they advance toward a meal distribution table. At the head of the line, a couple of men bow to fellow prisoners who are serving their food. An American serviceman stands by idly observing with a cigarette in his mouth.

After composing this watercolor, Tobita began drawing manically to alleviate his extreme anxiety and fear of execution as he awaited sentencing before the Tokyo Trials. Reflecting this mood, his earliest drawings took up haunting scenes, such as the routine cavity searches of naked convicts and the confiscation of shaving razors by guards at public baths. In one such troubled drawing (Figure 5), a prisoner struggles with insomnia while his cell mates sleep through an onslaught of threatening noises that breach the vent in their prison cell door. While most of the men snore, two are shown experiencing dark nightmares, as indicated by image-filled “speech” bubbles, one with a horn-headed monster and the other a knife-wielding assailant and bomber plane flying overhead.

Figure 6. The cover page of P-ko Sugamo Seikatsu, a scrapbook containing sixty-six sheets of hand-colored 4-coma (4 panels per page) “gag” manga strips by Fumio Fujiki. This serialized cartoon strip, named after the “everyman” prisoner, “Mr. P-ko” often appeared in the bi-weekly prison newspaper, “Sugamo Shimbun.” Hand painted on paper, 24.8 x 17.1 cm. Fumio Fujiki and Tokio Tobita collection, The Ohio State University, Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum; SPEC.CGA.SUG.2012.

Fumio Fujiki, “P-ko” and the Humbling Realities of Daily Life

As Tobita depicted early tensions between the American jailers and Japanese prisoners, other amateur artists emerged who copied his work and took up new themes. According to Powell and Du (2015), the Sugamo Project was ultimately able to identify nine prison artists whose work resembles Tobita’s. Among these, many took up the theme of prostitution, a flourishing post-war business that the Japanese convicts recognized just beyond the prison gates.

One of the most prolific prison artists was Fujiki Fumio, who, like Tobita, spent his time sketching and drawing while awaiting and eventually serving his sentence for Class-C war crimes. However, in contrast to Tobita, a poorly educated peasant from Ibaraki prefecture, Fujiki hailed from Osaka, attended private schools, and was tutored in English. One of the more sophisticated inmates, he was able to use his foreign language skills to form important connections with the prison guards. These relations, in turn, influenced his artwork in various ways. Despite never having been trained, he enjoyed drawing and studying caricature and cartooning manuals that the Americans shared with him in prison. He subsequently composed some of his cartoons in English for the entertainment of the Americans (Figures 7 and 8). Soon after his release, he drew on these experiences to publish his first book, Nakiwarai Sugamo nikki (or, roughly translated Laughing While Crying: The Sugamo Prison Diary) in 1953.

Figure 7. Suggesting an acute awareness that his audience included American prison guards, the artist Fumio Fujiki sometimes wrote his comics in English. In this example from P-ko Sugamo Seikatsu, Fujiki pokes fun at the strange relations that developed between the American soldiers and Japanese war criminals. Presumed adversaries, they test prison regulations by enjoying a game of chess together, a shared prison infraction that even the “chief jailor” is willing to commit. Handpainted on paper, 24.8 x 17.1 cm. Fumio Fujiki and Tokio Tobita collection, The Ohio State University, Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum; SPEC.CGA.SUG.2012.

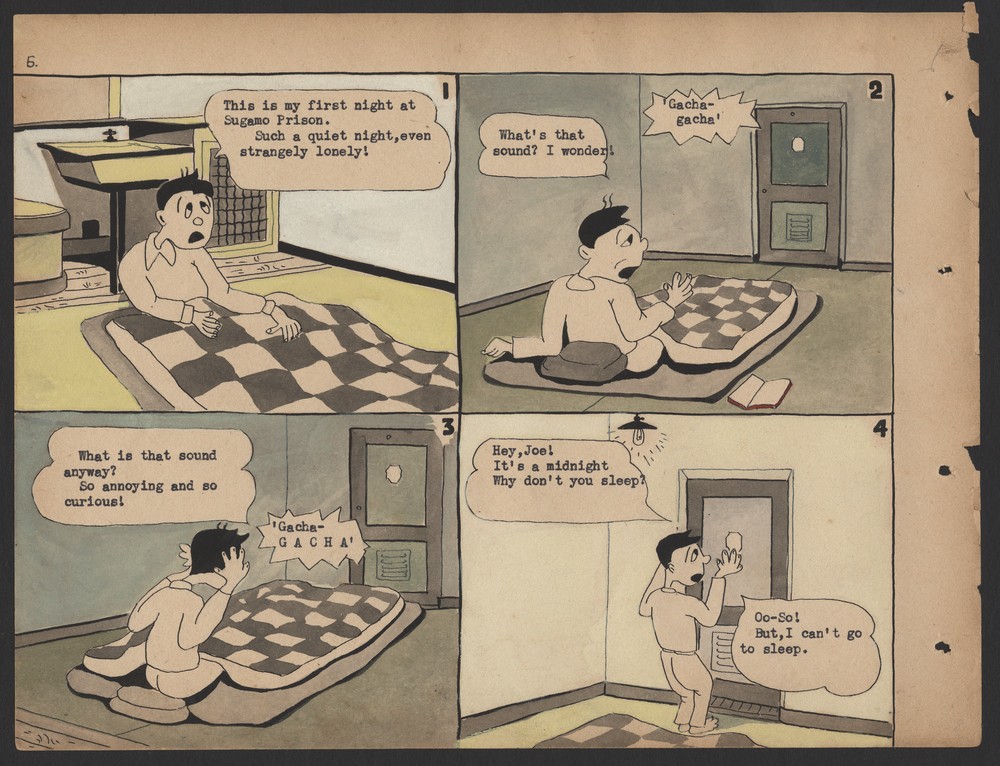

Figure 8. English language cartoons from P-ko Sugamo Seikatsu created by Fumio Fujiki. Here the artist shares with American soldiers the perspective of the Japanese inmate as he is frequently woken up by inexplicably loud and ominous sounds in the middle of the night. Handpainted on paper, 24.8 x 17.1 cm. Fumio Fujiki and Tokio Tobita collection, The Ohio State University, Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum; SPEC.CGA.SUG.2012.

Occupation authorities officially sanctioned drawing in the prison in 1948. At this time, Fujiki was assigned to serve out his hard labor sentence with Tobita at the newly formed Sugamo Prison Art Shop. Together the two collaborated on several submissions of cartoon drawings for The Sugamo Weekly News (すがも新聞 Sugamo Shimbun). Honing his skills, Fujiki next created a serialized comic strip for the same newspaper. Named after its main protagonist “P-ko” (P公), the series featured a composite “everyman” who wore a standard American-issued prison uniform that the inmates were required to paint with the letter “P” (Figure 6).

In the current collection at the Billy Ireland, scrapbook cut-outs of “P-ko” reveal that Fujiki, like many of the other prison artists, did not shy away from difficult topics. In one of his four-panel strips (subtitled “Hubba Bubba Joe”), for example, he deals head on with the humbling reality of post-war prostitution. As Fujiki confirms, the dire circumstances of the war had forced many Japanese women unexpectedly into the so-called “water trade” in order to survive. In the second strip from right (Figure 9), he pokes fun at this shameful situation by depicting P-ko’s encounter with a prostitute whom he calls beautiful. After exchanging a few words with her, however, P-ko recognizes that the woman is his little sister, and thus startled, he stumbles out of his chair.

Figure 9. Four sample cut-outs of the serialized manga “Mr. P-ko” from The Sugamo Weekly News. In the second strip from the left, the main protagonist P-ko is thrilled to meet a prostitute only to discover that she is his little sister whom he has not seen in many years. Colored ink on paper. Fumio Fujiki and Tokio Tobita Collection, The Ohio State University, Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum; SPEC.CGA.SUG.2012.

Conclusion

The Fumio Fujiki and Tokio Tobita Collection is an invaluable resource that tells of somber scenes and difficult emotions experienced by the jailers and jailed alike at Sugamo Prison. The museum exhibits, oral interviews, and academic publications resulting from the Sugamo Project underscore the power and lasting impact of this important collection. While offering a rare window on the respective experiences of former war criminals, the collection also documents personal intimacies that were shared and unexpectedly treasured for decades after the American Occupation.

In many ways, the Sugamo artwork is more dynamic than spoken words or written text. To this day, the drawings and sketches in this collection teach about the profound human capacity for self redemption and communication across national and linguistic divides. Retrospectively, the collection imparts important lessons that go well beyond the common curriculum. As soldiers on both sides emerged from the dark chasm of war, the prisoner artwork became significant vehicles for reconciliation and friendship. Their story of human resilience and recovery offer an indispensable supplement for any history textbook. Art scholars and Japanese teachers as well will certainly draw vital lessons from these materials for decades to come.

0 Comments

1 Pingback