This post is authored by Heidi Bowles, current student at the UC Davis School of Law and former research assistant at Ohio State University Libraries’ Copyright Services.

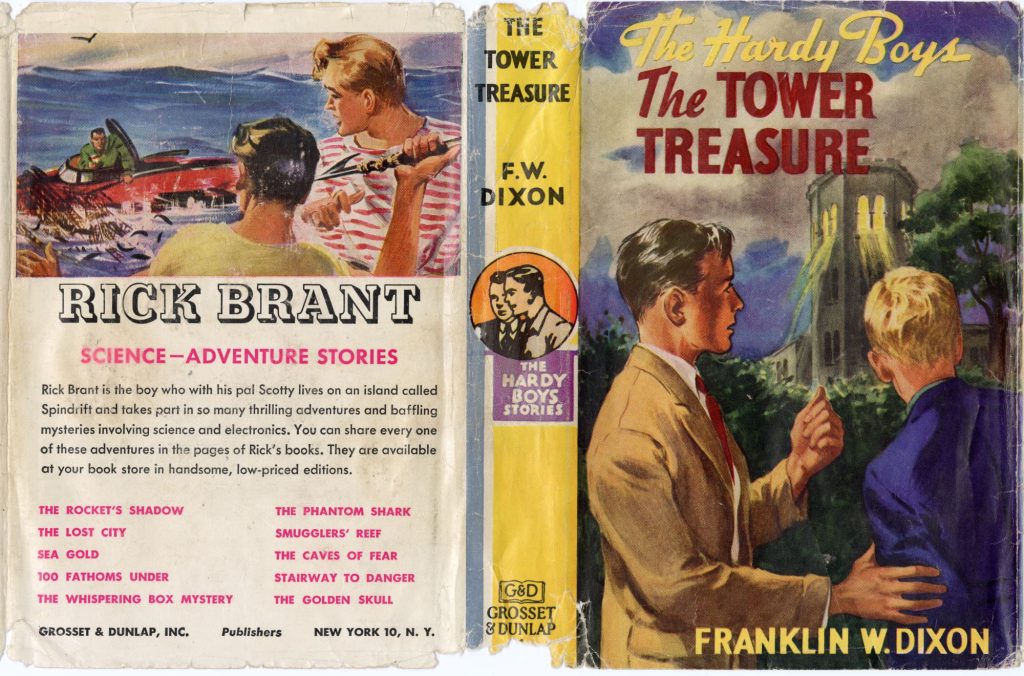

The first three novels of the popular children’s detective series The Hardy Boys (The Tower Treasure, The House on the Cliff, and The Secret of the Old Mill) entered the public domain on January 1, 2023, meaning that they are free from copyright protection in the United States. The Ohio State University’s Rare Books and Manuscripts Library has copies of the original 1927 editions of The Tower Treasure and The House on the Cliff.

The Hardy Boys was created by the Stratemeyer Syndicate and published by Grosset and Dunlap. The Syndicate was a book packaging company that produced many popular children’s series in the twentieth century, like Nancy Drew and The Rover Boys. To create so many books on a short timeframe, the Syndicate operated as a well-oiled machine that followed a standard process for creating a book: a Syndicate executive, often Edward Stratemeyer himself, produced a short outline of a story, which was provided to a contracted ghostwriter who then wrote it into a book for a flat fee. The book was then returned to a Syndicate executive for final edits before being sent to the publisher. When launching a new series, they would release three initial books to test whether or not there was a market for their idea. These first three test books for The Hardy Boys are now in the public domain.

In the early years of the series, Edward Stratemeyer provided the outlines to Leslie McFarlane, who wrote under the pseudonym Franklin W. Dixon. The first eleven books in the series were written by McFarlane, who also contributed to other Syndicate series under various pseudonyms. After Stratemeyer’s death in 1930, other Syndicate writers, including his daughter Harriet Stratemeyer Adams, contributed outlines to several uncredited ghostwriters writing as Franklin W. Dixon.

Copyright

The Copyright Act of 1909, which applies to works created before January 1, 1978, provided new works that followed proper formalities with a 28-year period of copyright protection with the option to renew the copyright for another 28-year period. Changes in the law (in the Copyright Act of 1976 and the 1998 Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act (CTEA)) extended the second period, making the maximum copyright term for published works covered by the 1909 Copyright Act 95 years from the date of publication.

Under the terms of an agreement between the authors and Stratemeyer Syndicate, copyright in the works appears to have been transferred and then registered in the name of the publisher (Grosset and Dunlap). Under the agreement, actual writers of the series did not receive a share of the royalties for sales of the books.[1] Franklin W. Dixon (a pseudonym) was listed as the author in the copyright registrations for many of The Hardy Boys novels, rather than the actual writers.

Under the 1909 Copyright Act, a publisher who was assigned copyright could control the copyright for the initial term, but the author, if still living, could claim the copyright for the renewal term. If the author was not living at the time of renewal, the copyright in the renewal term could be claimed only by those designated under the law. Harriet Stratemeyer Adams, who took charge of the Syndicate after her father’s death, renewed the copyrights in 1955 and claimed them for the renewal term.

The Syndicate’s practices of hiring contract writers and publishing series under a pseudonym let them control their stories and their legacies. They were able to authorize many spinoffs, adaptations, and revisions. In the 1950s and 1960s, during the renewal copyright term, the Syndicate shortened and revised the original Hardy Boys series. Although they were based on the original public domain books, these revisions are still protected by copyright.

Releasing these revisions did not restart the copyright in the original books—as derivative works, the elements taken from the original books are not copyrightable, only the new creative elements in the revised versions. The revised wording, revised characterization, illustrations and other new elements are protected by a separate copyright that will last for 95 years after publication.

Similarly, characters and events from the revised version or later iterations of the series are still protected by copyright. In the 1927 Tower Treasure, Frank and Joe Hardy were sixteen and fifteen years old but they were eighteen and seventeen in 1959. Only the sixteen-year-old and fifteen-year-old brothers are public domain.

The later revisions also altered the sidekick characters. One snarky review explains:

All the same, the Hardy Boys’ gang was a model of diversity for its day. In addition to best pal Chet Morton (or as he’s referred to in the original books, “the fat youth”), there was strongman Biff Hooper and two bona fide ethnics—Phil Cohen, a brainy Jewish kid; and Tony Prito, who is so darned ethnic that his poor Italian-accented English is the subject of good-natured mirth in the 1927 version of “The Tower Treasure.” In the 1959 rewrite, the melting pot has done its work and only the ethnic names remain. Tony Prito becomes “a lively boy with a good sense of humor.” Phil Cohen is “a quiet, intelligent boy.”

Characters and their characterization are copyrightable elements of a story, so only the version of the characters as they appear in these three 1927 books are in the public domain. Later updates to the specific characters are still protected by copyright. The stereotypical versions of Tony Prito and Phil Cohen are in the public domain, but the homogenized versions are not. Anyone making an adaptation or using these characters should be careful to avoid using any later versions of the character to avoid copyright issues.

This does not mean that any adaptation has to include these characters as they exist in the 1927 books. They can be changed and updated; it is just important to make sure that any changes to the characters have not already been made in copyrighted materials. To take clothing as an example, an adaptation would not have to dress the brothers in their original 1920s clothing simply because that version is in the public domain. There would be no copyright issues with styling the brothers as punks with pink mohawks and leather jackets (assuming that no copyrighted version like this already exists). There might, however, be copyright issues with dressing them in sweaters and denim as they appear in the 1950s.

Public Domain

Now that these books are in the public domain, they can be freely copied, adapted, distributed, performed, and displayed without having to seek permission from a rightsholder, negotiating a license, or paying royalties. This means that they can be posted online so they are more easily available for researchers and general readers, and they can be adapted by creators.

Public domain children’s books are particularly valuable because they are more accessible to children who do not live near a library and cannot afford to buy their own books, and, as the Authors Alliance pointed out, there is a severe lack of children’s books in many non-English languages. Public domain books are easier and cheaper to translate into languages with fewer available books.

Public domain materials are also available to be updated to address past injustices. The original Hardy Boys books were filled with racist and sexist stereotypes, and other reflections of 1920’s white male middle-class prejudice.[2] These books have sentimental value for many, and their enduring popularity makes them important material for researchers. Although these books might not be the best option to give to children, it is important to preserve and understand the underlying values of a series that many remember fondly as a part of their childhoods.

The public domain is a valuable and essential part of the lifecycle of copyright that makes creative works available to be freely used and inspire new works. This year, many important and interesting works entered the public domain. A few other notable works include:

- Virginia Woolf’s To The Lighthouse

- Sinclair Lewis’s Elmer Gantry

- Langston Hughes’s Fine Clothes to the Jew

- Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein’s Show Boat

- Georgia Douglas Johnson’s Plumes: A play in one act

- John Dewey’s The Public and Its Problems

Learn more about how Ohio State is celebrating the public domain at go.osu.edu/PublicDomainDay.

[1] For more about the history and business practices of the Stratemeyer Syndicate, see Carol Billman’s 1986 book, The Secret of the Stratemeyer Syndicate: Nancy Drew, The Hardy Boys, and the Million Dollar Fiction Factory (link to OSUL catalog).

[2] For an analysis of The Hardy Boys series, see Joe Arthur’s 1991 OSU dissertation, “Hardly Boys: An Analysis of Behaviors, Social Changes, and Class Awareness in the Old Text of the Hardy Boys Series.”

Recent Comments