The Story of The Story of Mankind

Hendrik Willem van Loon was destined to be a popularizer. After graduating from Cornell University, van Loon worked as a journalist for the Associated Press in Russia and Poland, before pursuing his PhD in history at the University of Munich. While writing his dissertation, van Loon chafed at the dry conventions of academic prose (which he found dull and lifeless) and sought instead to write as he did as a journalist: in clear, engaging prose that was intelligible to an educated reader. (His dissertation later became his first book, the popular The Fall of the Dutch Republic.) Van Loon claimed that, in writing and illustrating popular books on history, he wanted to bring learning and education to the masses at a time when few people attended college.

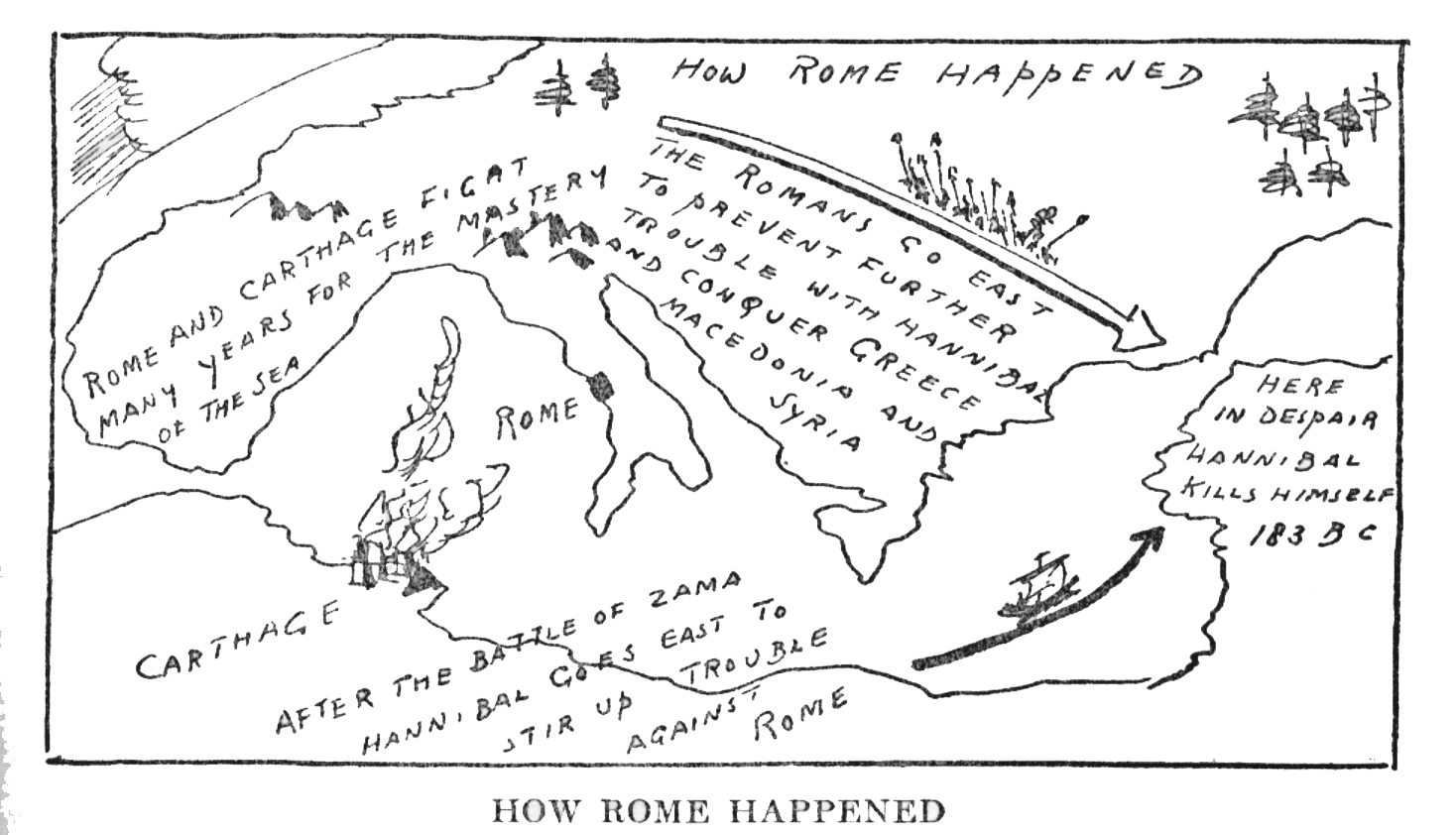

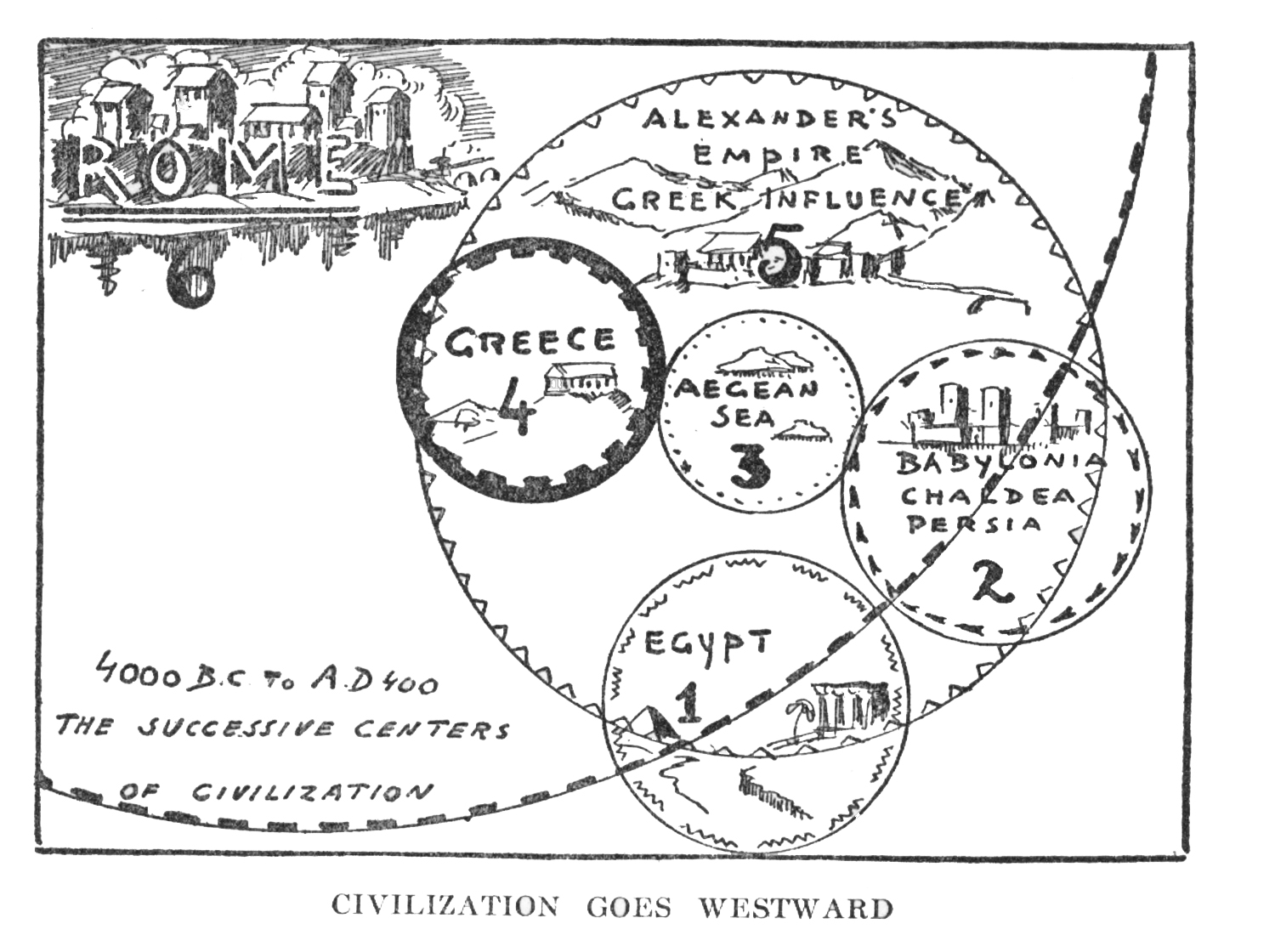

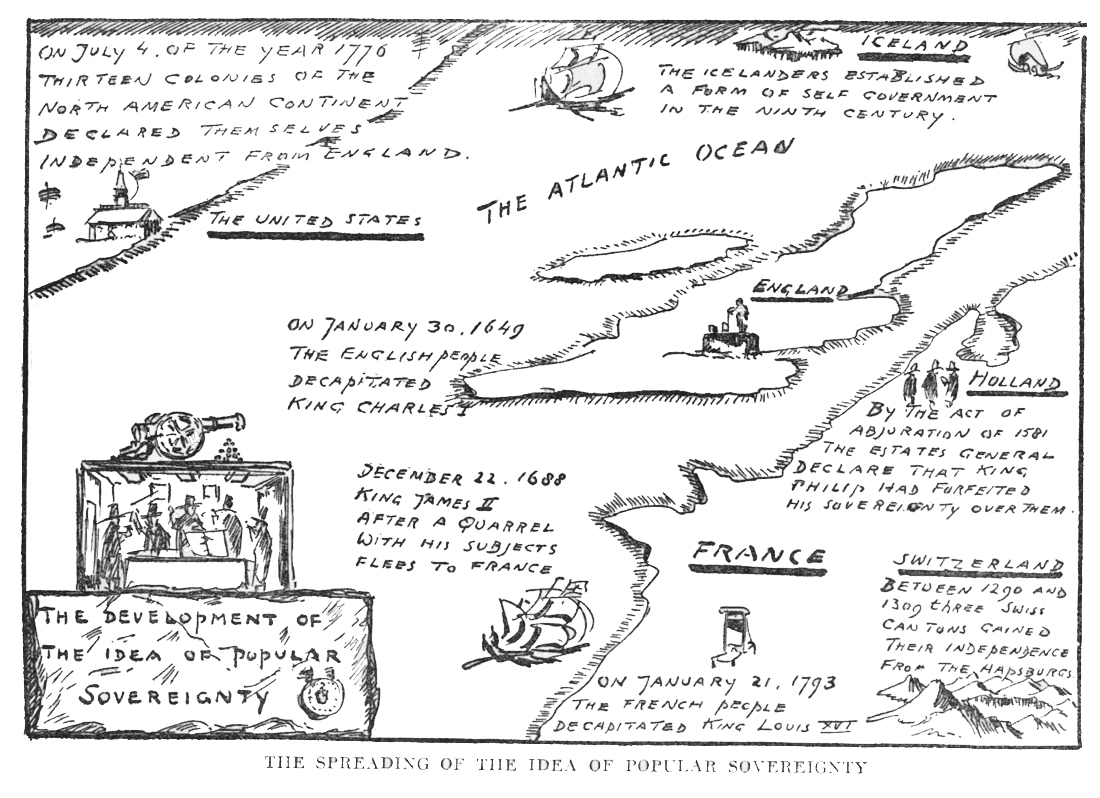

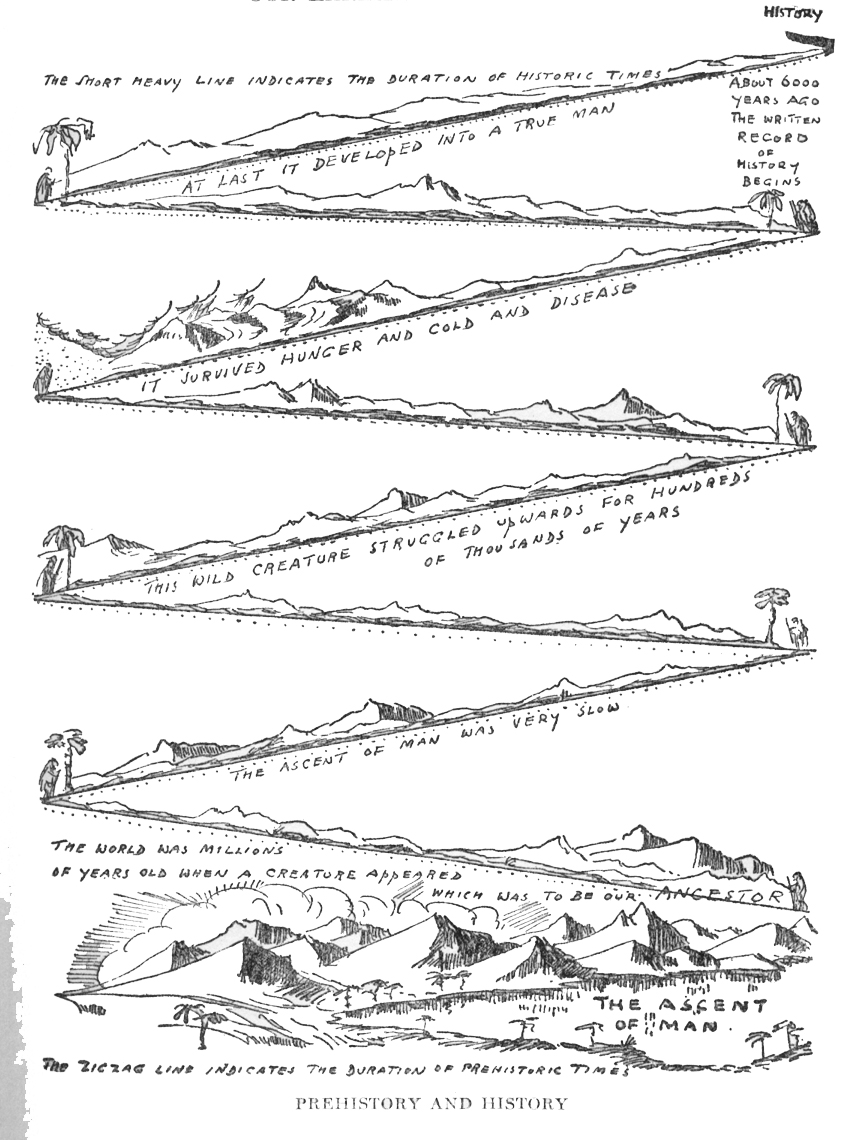

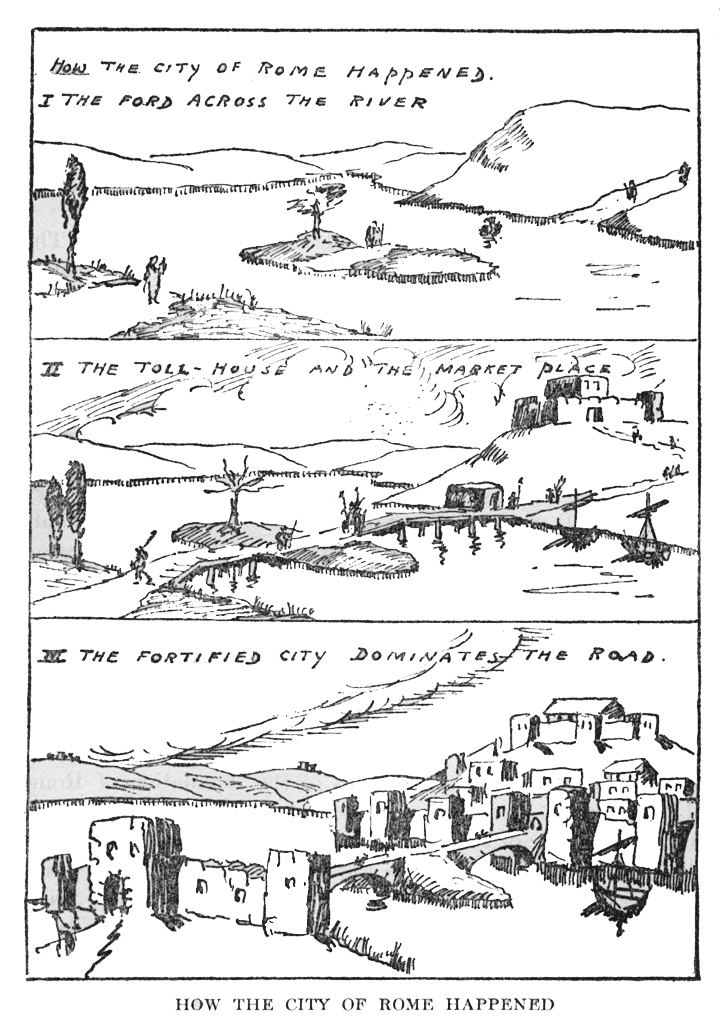

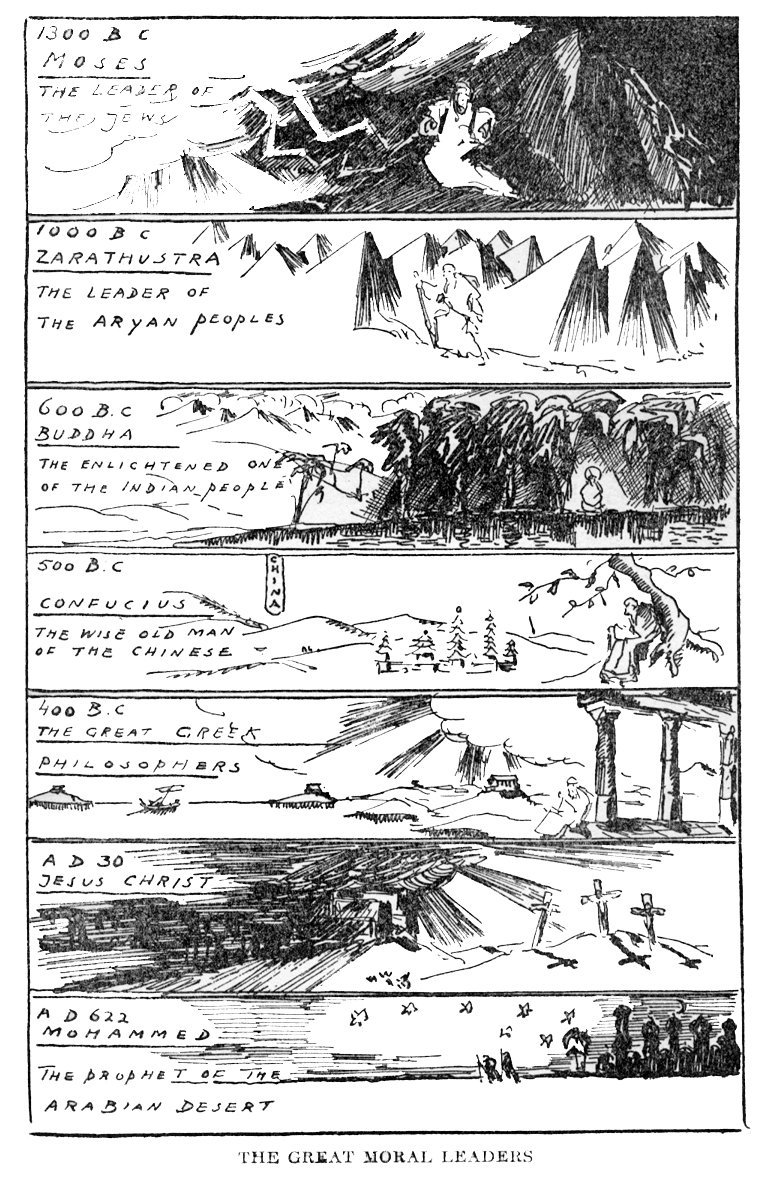

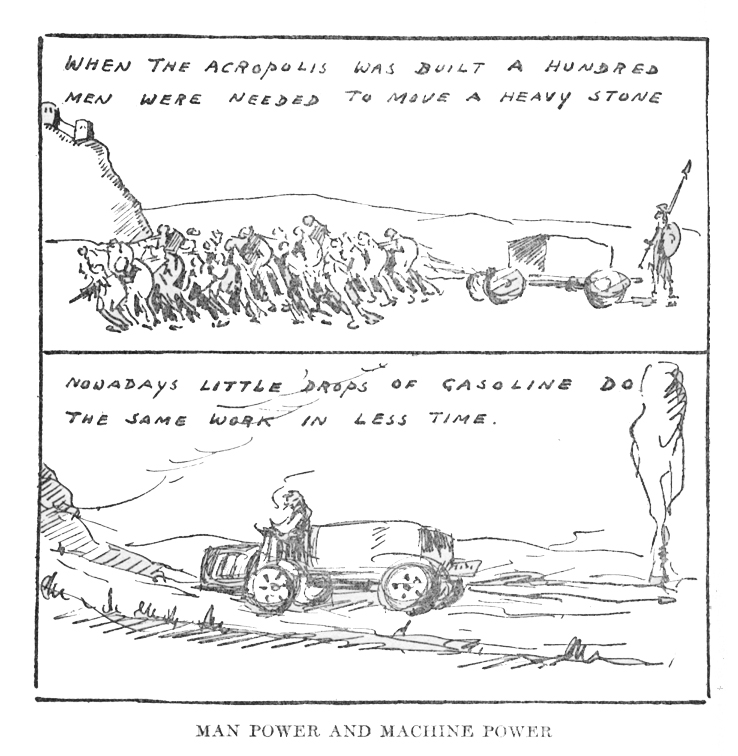

After writing a favorable review of H. G. Wells’ Outline of History (the standard work of popularized history), van Loon was approached by his publisher to write and illustrate a similar outline of world history aimed at schoolchildren. Van Loon wrote and illustrated the first draft of the book in two months, playfully suggesting that unlike Thucydides and Ranke, who had merely written their histories, he was the greater historian since he had both written and drawn his history. Van Loon hoped that publication of The Story of Mankind would mean that “no professor doctor hereafter, can write quite the same sort of dull history that has been forced upon children thus far.”

In addition to its voluminous sales, The Story of Mankind was widely praised by reviewers, some comparing it favorably to Wells’ Outline, but not by all academic historians. History professors long remained a foil for van Loon (largely because he wanted to join their ranks). These professors criticized the book for its sometimes simplistic interpretations (not out of line for a book designed for children) and for its factual errors. Despite these criticisms, in June 1922, The Story of Mankind received the first John Newbery Medal awarded by the American Library Association for the year’s most distinguished contribution to children’s literature.

In addition to its voluminous sales, The Story of Mankind was widely praised by reviewers, some comparing it favorably to Wells’ Outline, but not by all academic historians. History professors long remained a foil for van Loon (largely because he wanted to join their ranks). These professors criticized the book for its sometimes simplistic interpretations (not out of line for a book designed for children) and for its factual errors. Despite these criticisms, in June 1922, The Story of Mankind received the first John Newbery Medal awarded by the American Library Association for the year’s most distinguished contribution to children’s literature.

The Story of Mankind was an important example of what historian Joan Shelley Rubin refers to as “the outline craze” of the 1920s and 1930s. At a time when knowledge was growing ever more specialized, popularizers like van Loon, Wells and Will Durant wrote books that sought to present a broad picture of the state of human knowledge, to bring meaning to a world whose knowledge was at once expanding and fracturing.

The Story of Mankind remains in print today and has even recently been “updated for the new millennium.”