Van Loon the Illustrator

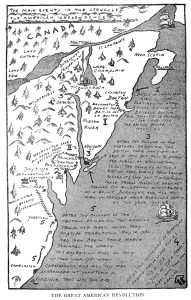

Although he had no formal training in art, Hendrik Willem van Loon was as prolific an illustrator as he was a writer. Every one of his forty-plus books featured his drawings, maps and sketches, and many of his newspaper columns similarly were accompanied by drawings. Other authors would often commission Van Loon to illustrate their books as well.

Although he had no formal training in art, Hendrik Willem van Loon was as prolific an illustrator as he was a writer. Every one of his forty-plus books featured his drawings, maps and sketches, and many of his newspaper columns similarly were accompanied by drawings. Other authors would often commission Van Loon to illustrate their books as well.

Van Loon proclaimed that:

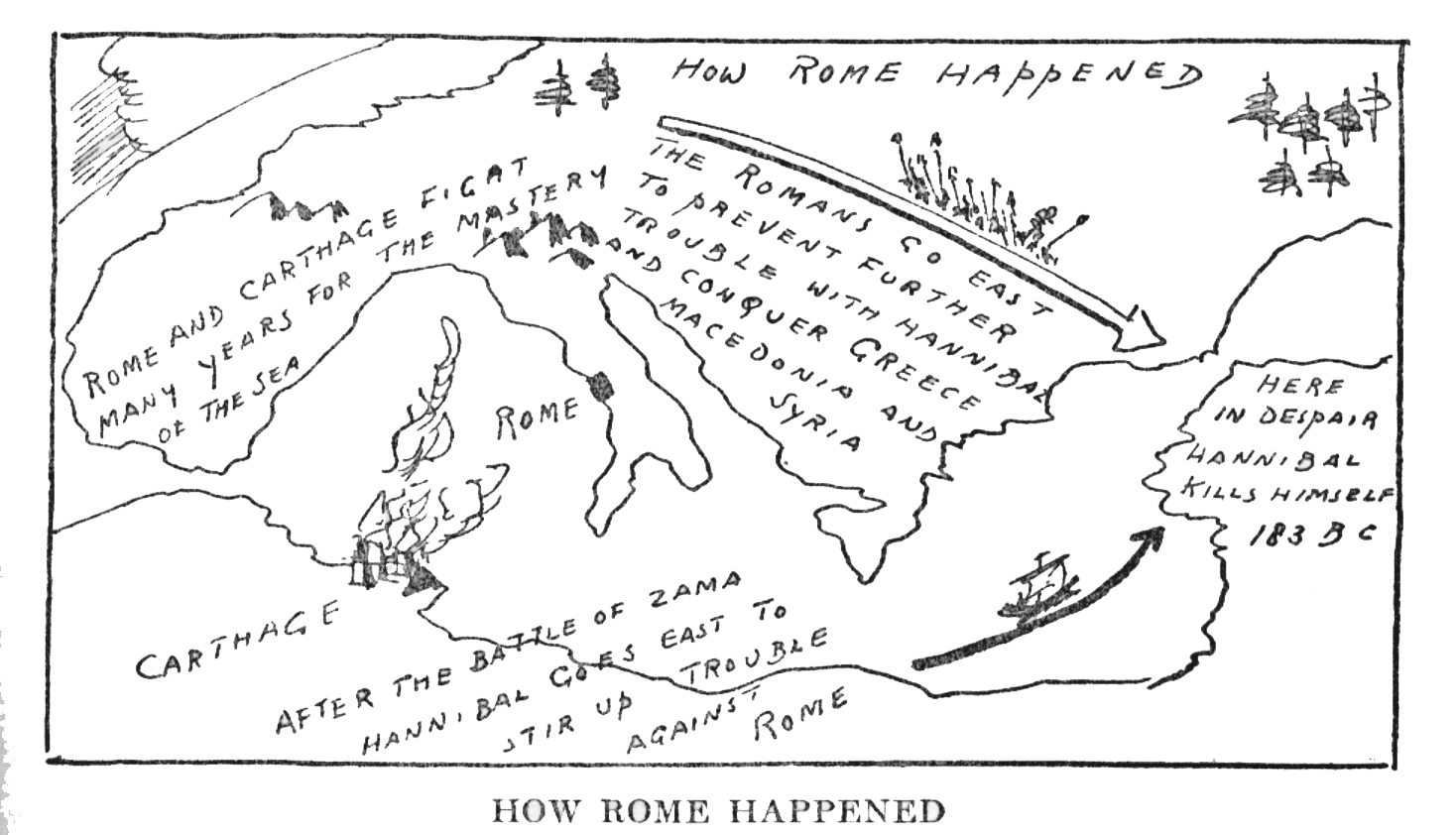

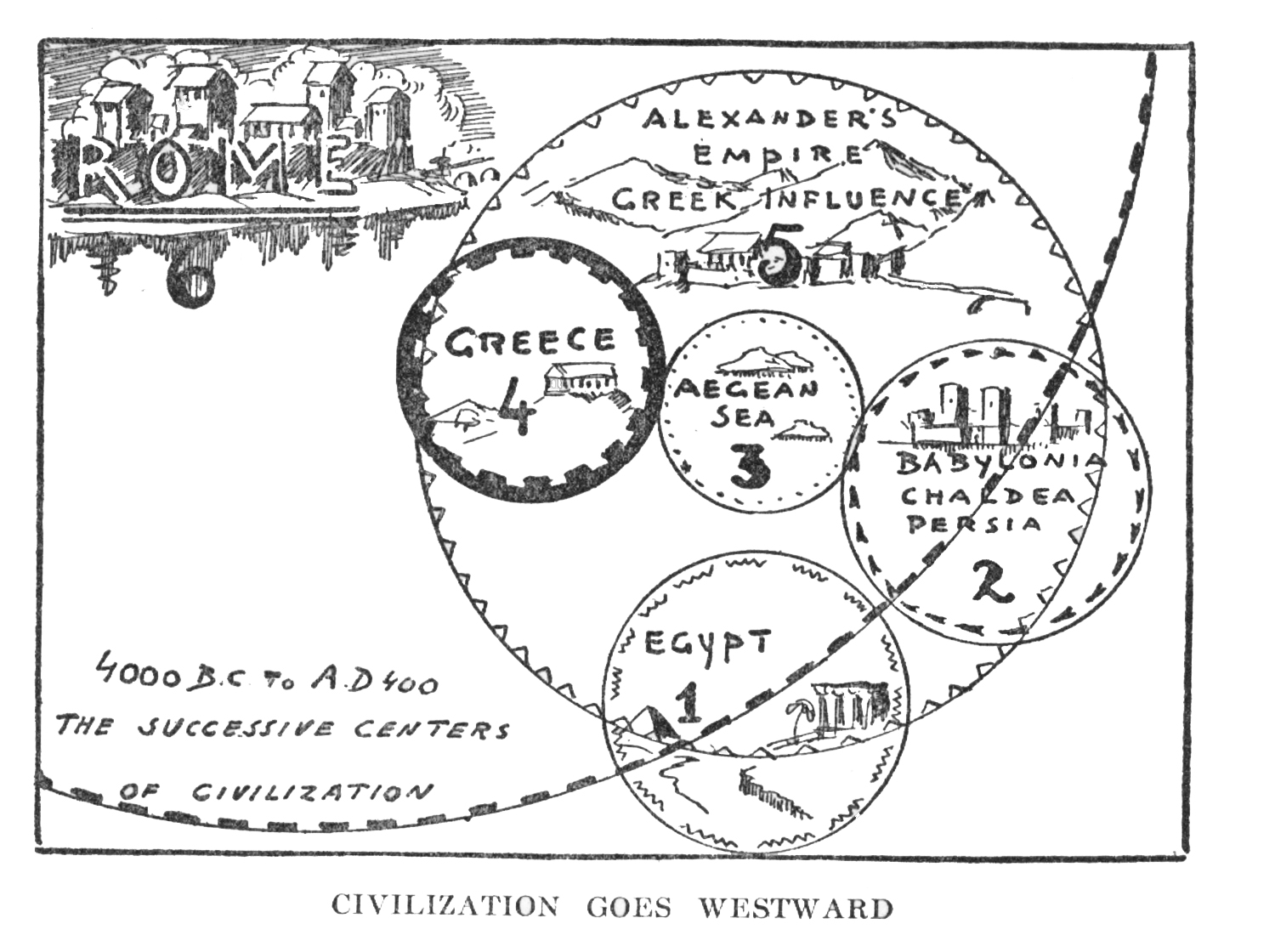

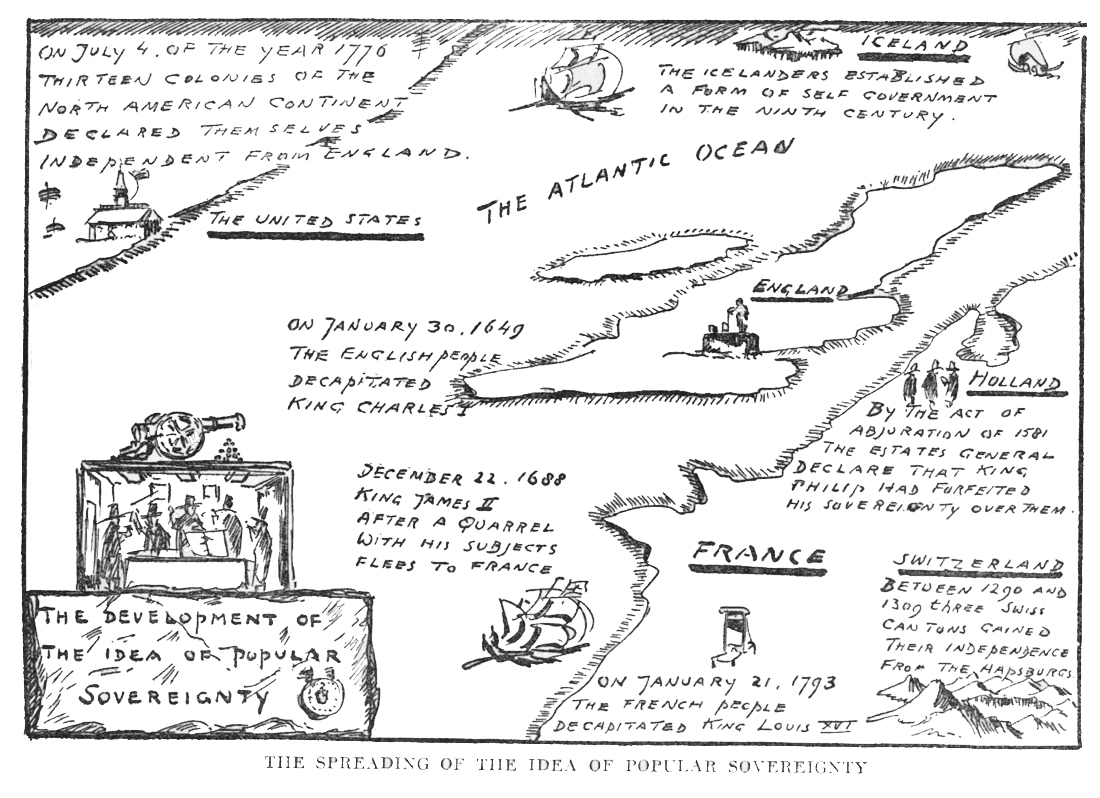

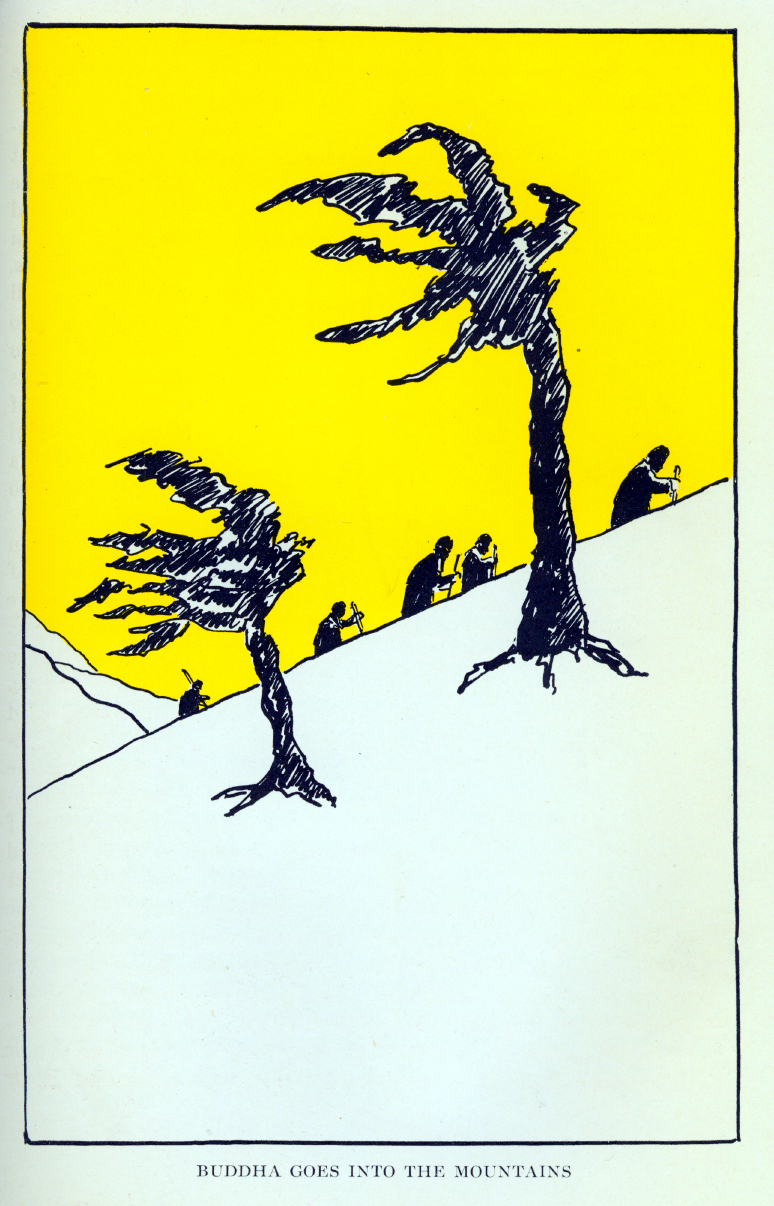

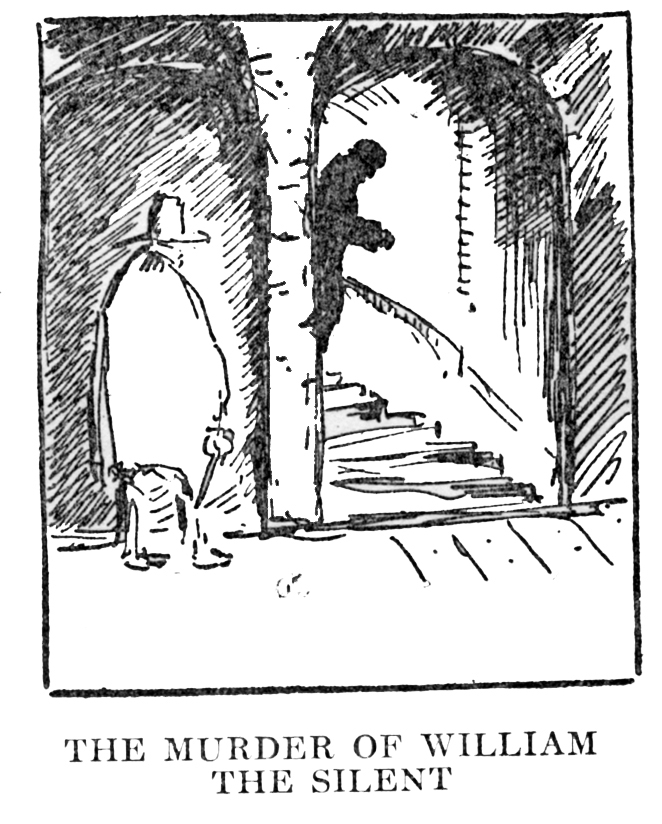

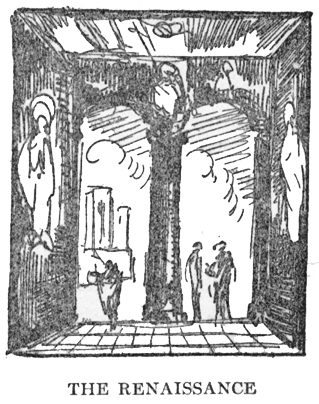

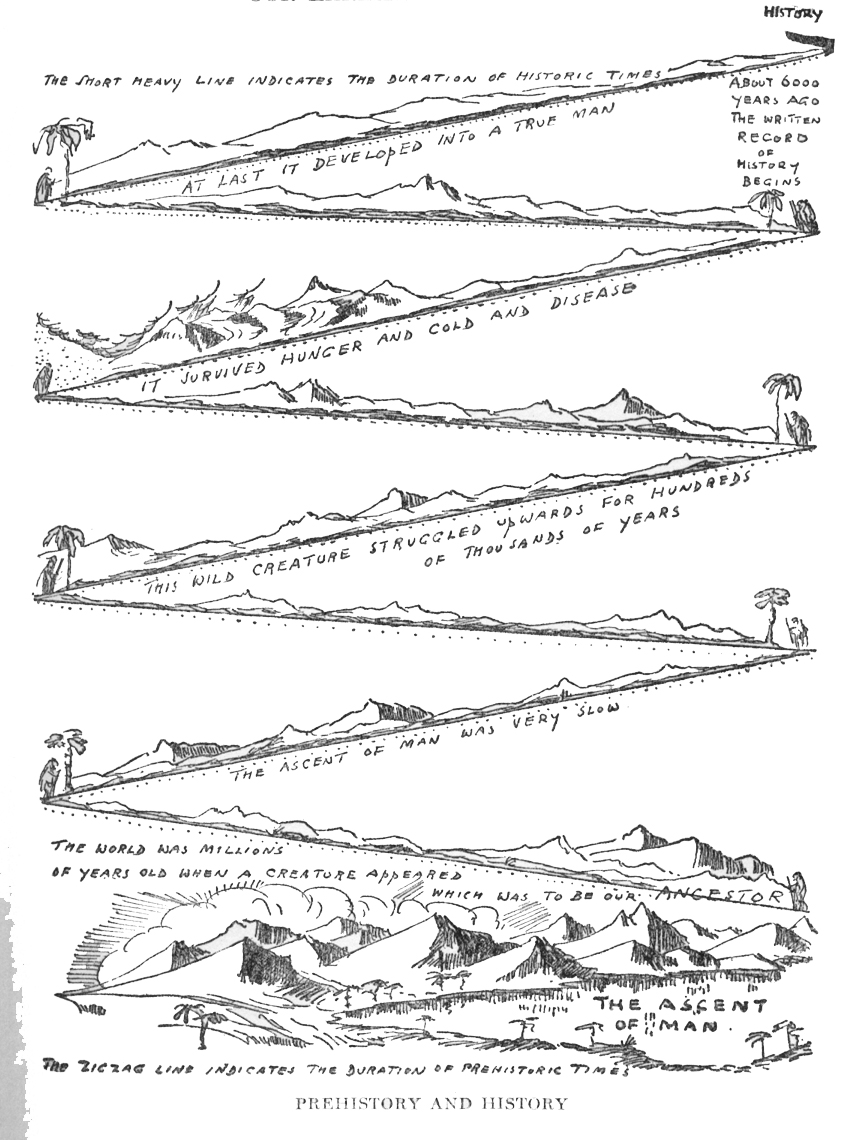

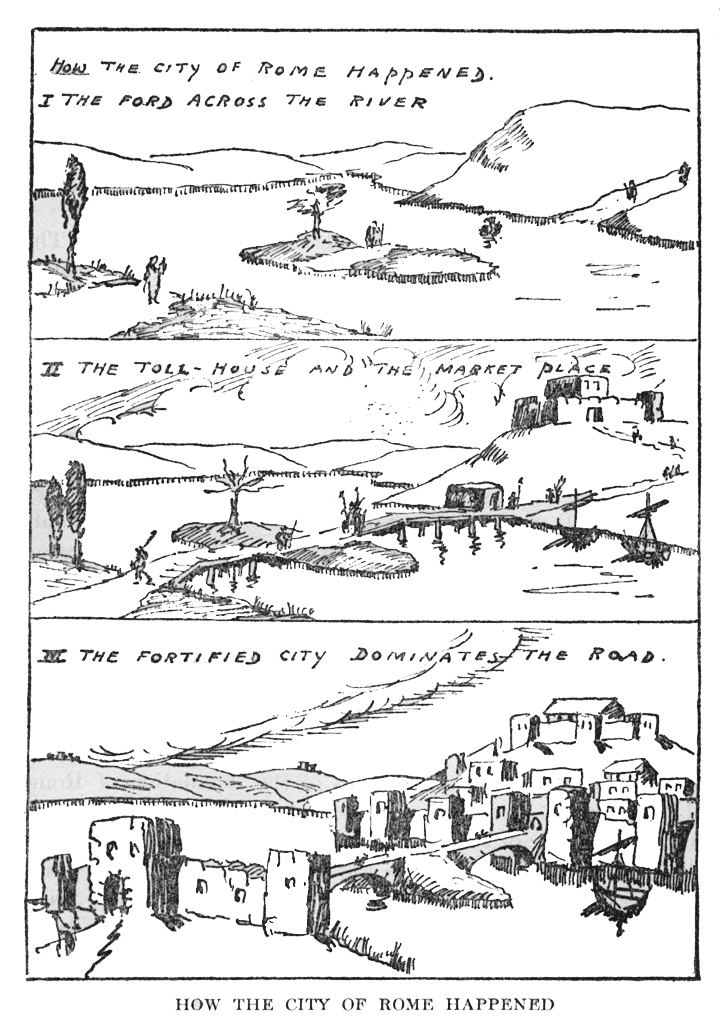

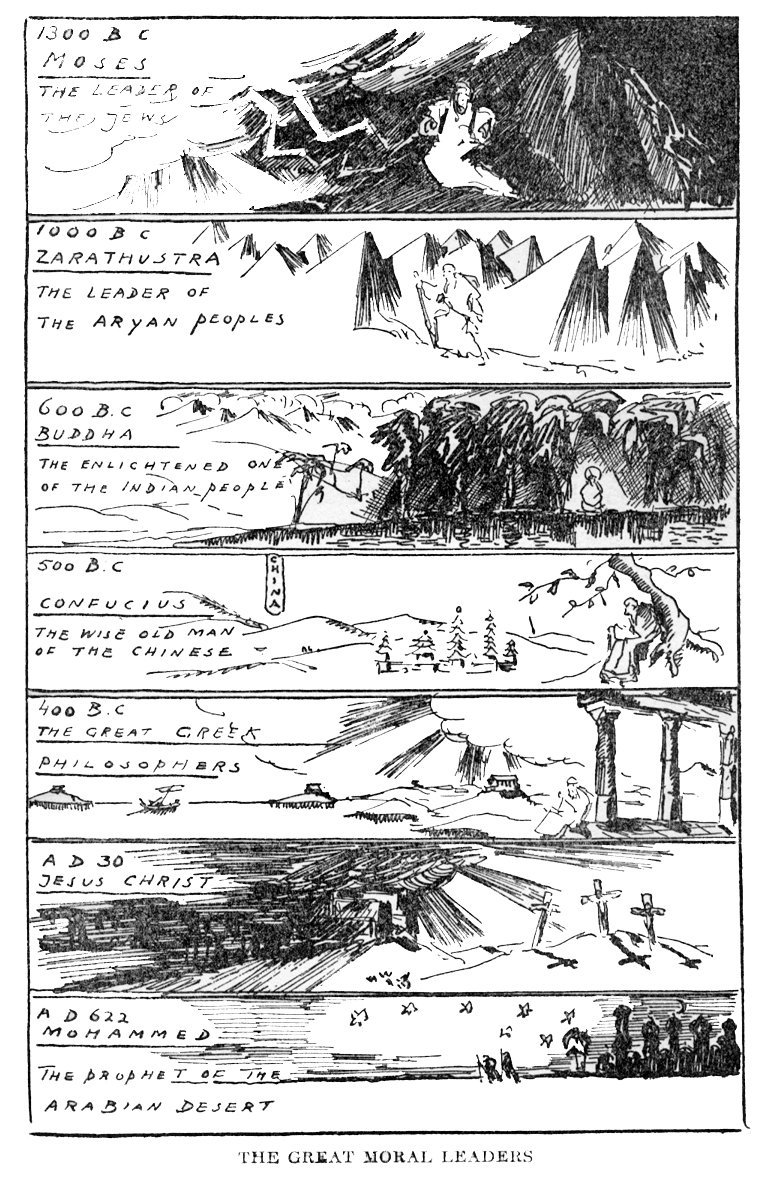

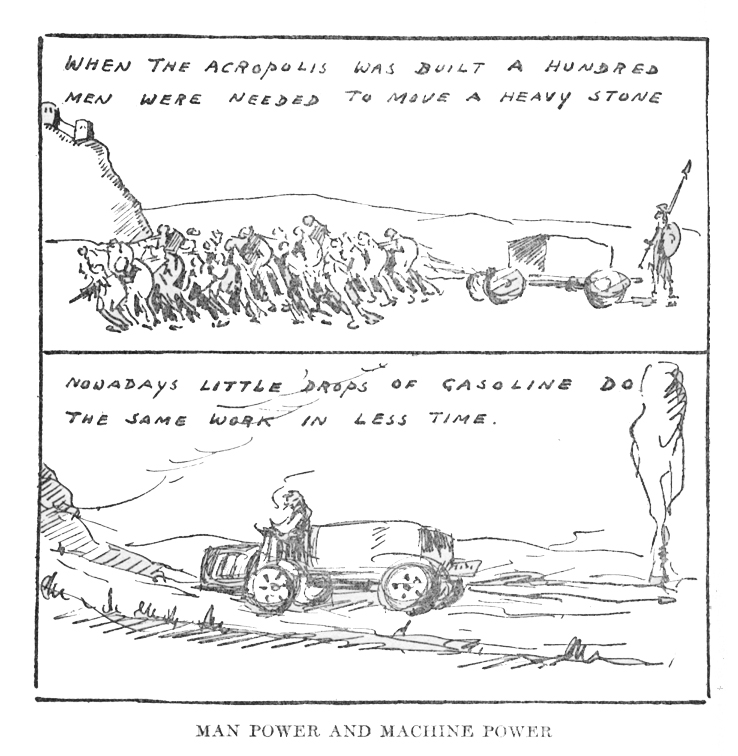

most writers can only write and most artists can only art. But I can do both and so I ought to make my books into something like a good Wagner opera and make the pictures carry the text and vice versa.

Van Loon’s impulse to draw found expression in a variety of forms. At both Cornell and Antioch, van Loon would arrive in class with a large pad of paper, upon which he would draw impromptu sketches to illustrate his lectures. When dining with friends, he would animate his conversations with drawings scribbled on the table cloths; when delivering his radio broadcasts, he would doodle and scribble. He would even draw pictures directly upon the walls of his study.

Van Loon’s impulse to draw found expression in a variety of forms. At both Cornell and Antioch, van Loon would arrive in class with a large pad of paper, upon which he would draw impromptu sketches to illustrate his lectures. When dining with friends, he would animate his conversations with drawings scribbled on the table cloths; when delivering his radio broadcasts, he would doodle and scribble. He would even draw pictures directly upon the walls of his study.

Of the drawings in The Story of Mankind, van Loon said:

Of the drawings in The Story of Mankind, van Loon said:

While the author lays no claim to great artistic excellence…he prefers to make his own maps and sketches because he knows exactly what he wants to say and cannot possibly explain this meaning to his more proficient brethren in the field of art.

Moreover, van Loon believed that this impulse to draw should be a part of every child’s education:

Moreover, van Loon believed that this impulse to draw should be a part of every child’s education:

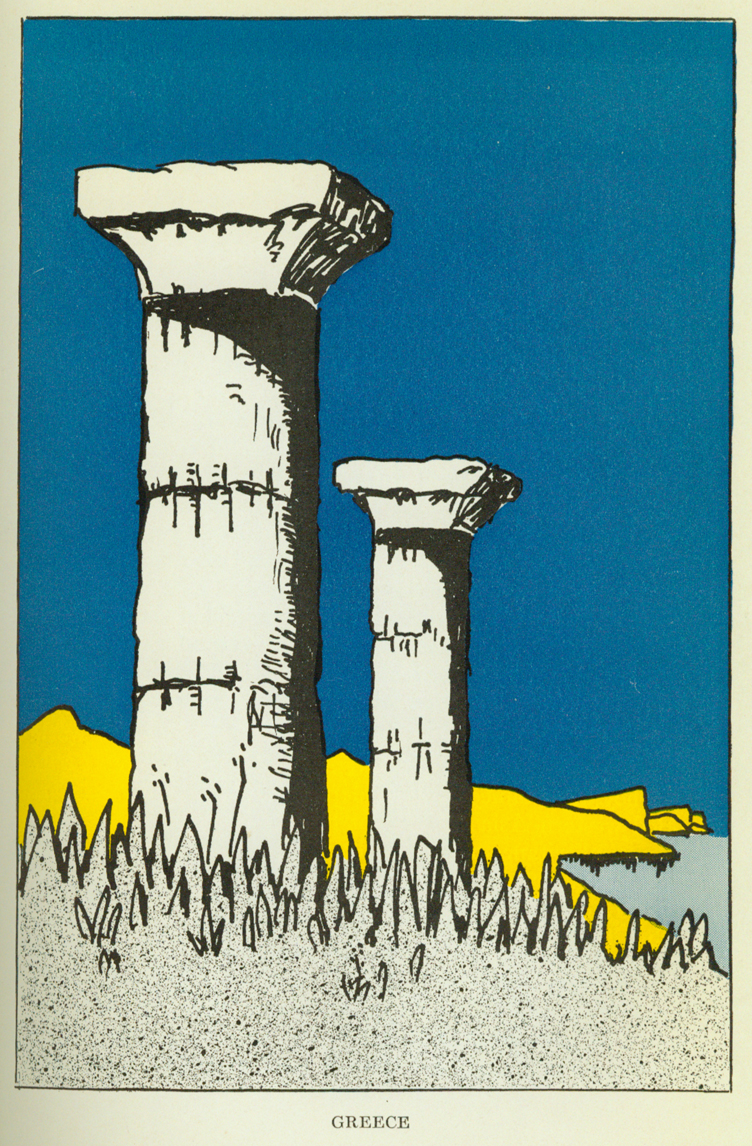

To all teachers the author would give this advice—let your boys and girls draw their history after their own desire just as often as you have a chance. You can show a class a photograph of a Greek temple or a mediaeval castle and the class will dutifully say, “Yes, Ma’am,” and proceed to forget all about it. But make the Greek temple or the Roman castle the centre of an event, tell the boys to make their own picture of “the building of a temple,” or “the storming of the castle,”

and they will stay after school-hours to finish the job…The experiments of many years in the Children’s School of New York has convinced the author that few children will ever forget what they have drawn, while very few will ever remember what they have merely read.

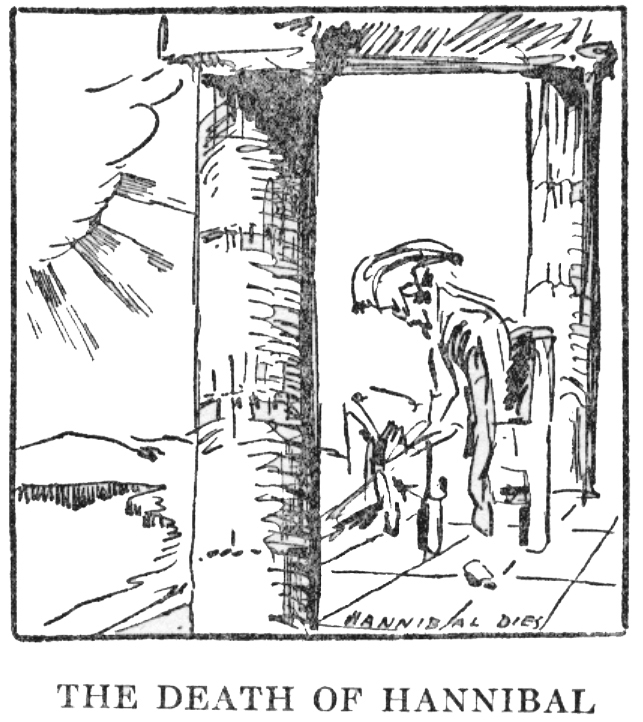

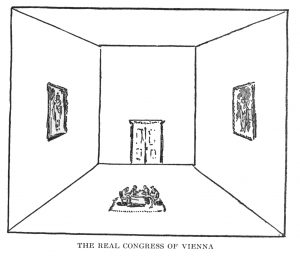

Van Loon’s drawings are difficult to categorize as art objects. They are at once echoes of historical genre paintings, in that they are formal visual depictions of historical events, but they are more similar in style to editorial cartoons. (One is reminded of Gustav Dore or Goya’s sketches of the Napoleonic wars collected under the title The Disasters of War.) Van Loon’s drawings were typically allegorical rather than strictly mimetic or representational. Look, for example, at “The Real Congress of Vienna,” which is less a mimetic reconstruction of an event than a commentary, an editorial. In the drawing, van Loon draws a few diplomats and statesmen in a cavernous hall redesigning Europe, symbolizing the event as anti-democratic and non-participatory. The illustrations chosen for this exhibition have been selected to draw attention to these allegorical, symbolic and editorial features.

Van Loon’s drawings are difficult to categorize as art objects. They are at once echoes of historical genre paintings, in that they are formal visual depictions of historical events, but they are more similar in style to editorial cartoons. (One is reminded of Gustav Dore or Goya’s sketches of the Napoleonic wars collected under the title The Disasters of War.) Van Loon’s drawings were typically allegorical rather than strictly mimetic or representational. Look, for example, at “The Real Congress of Vienna,” which is less a mimetic reconstruction of an event than a commentary, an editorial. In the drawing, van Loon draws a few diplomats and statesmen in a cavernous hall redesigning Europe, symbolizing the event as anti-democratic and non-participatory. The illustrations chosen for this exhibition have been selected to draw attention to these allegorical, symbolic and editorial features.