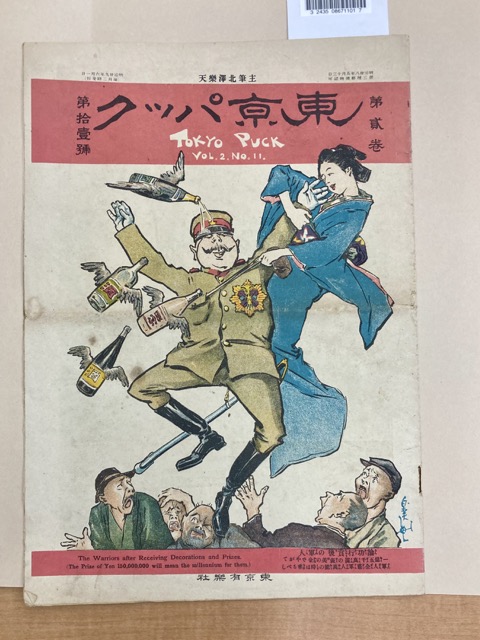

Cover image of a newly ingested issue

of Mangajin, Vol. 1, No. 4, October 1990.

Recently we received a wonderful donation of manga and manga ephemera from Dr. Lynne Miyake, manga scholar and Emerita Professor of Japanese at Pomona College. With a plethora of unique titles, I’d like to introduce just a few of the exciting finds that are now available through this donation!

Are you a fan of manga magazines? If so, this is the collection for you. The Miyake donation adds 94 manga volumes from a variety of genres and titles from the years 2002 to 2016 to our holdings. These include lesser-known to more mainstream titles such as Shonen Jump, Morning, Cheri+, Ciel, OTAKU USA, and more. Many of these volumes fill in gaps in our catalog for circulating manga as well as special collections at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum. For instance, thanks to the Miyake donation (which adds volumes from May through December 2003), our holdings of of Shonen Jump now run uninterrupted from 2003 to 2009!

Kashimashi Vol. 1 by Satoru Akahori

(あかほりさとる) and illustrated

by Yukimaru Katsura (桂遊生丸)

If understanding Japanese manga in translation or research on earlier manga culture is your thing, you’ll be happy to hear that we have also ingested three additional volumes of Mangajin, the definitive manga magazine in the U.S. pre-2000, dating from 1990 and 1993.

Aside from these, the majority of the magazines are from well-known boys’ love (BL) publications, a welcome addition to the Cartoon Library collection, which emphasizes LGBT+ titles. In fact, one of the strengths of this donation is its LGBT+ offerings, both in English and Japanese.

For example, we now have several volumes of Kashimashi: Girl Meets Girl, a quirky yuri (or “girls love”) comedy about a male student who dies and is resurrected as female. Suddenly the girl she likes, who is only capable of noticing other girls, is falling for her. But soon a love triangle forms and the complicated story twists even more! Though it may seem strange on the surface, this title has been praised for its unique story and characters and is definitely worth a look.

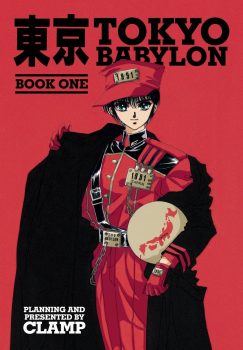

Tokyo Babylon written and

illustrated by CLAMP

We also now have volumes one through seven of Tokyo Babylon in English, a series mentioned in our April 2021 blog “Checking Out Manga.” Published by acclaimed all-female manga circle CLAMP, “Tokyo Babylon” chronicles sorcerer Subaru’s work solving mysteries while adding a boys’ love twist later into the plot.

Finally, this donation also adds several unique art books to the distinctive holdings, held at BICLM. Of these, possibly the most stunning is Der Mond: The Art of Neon Genesis Evangelion based on the tremendously popular manga and anime series Neon genesis Evangelion. This art book is for the fans especially, but also those who are interested in learning more about the visuals. A large format print, the book brings to life the world of Evangelion’s manga adaptation in full color.

Der Mond by Yoshiyuki Sadamoto

(貞本義行)

There are so many more books as well as other rare and distinctive materials, including posters, conference booklets, and even original art! Stay tuned as we continue to process these unique materials and make them available for research and teaching. In the mean time, we’d like to extend a heartfelt thank you to Professor Miyake for her generous donation!

![Cover art for "Ten Count" vol. 1 [Aug. 9, 2016]](https://library.osu.edu/site/manga/files/2022/06/IMG_0138-245x350.jpeg)