Emily is an English major pursuing a career in library science. She has worked at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum for two years. She is interested in comics and 19th century medical history.

In addition to working at the Billy Ireland, I’ve had the privilege of collaborating with Professor Jared Gardner on the Drawing Blood website. The site began as an accompaniment to the exhibit Drawing Blood: Comics and Medicine, which Gardner curated for the Billy Ireland in 2019. Since then, Gardner and I have been developing the site into a scholarly resource that documents the shared history of comics and medicine. We hope to show how the popular medium of cartoon art has played an integral part throughout the history of medicine. Careful attention to medical prints and cartoons can lend contextual understanding of both medical and print history. They reveal not only how the field developed, but why as well.

In this promotional post, I’ve selected two items from the Billy Ireland’s wonderful Hale Scrapbook to show you.

Both prints are by George Cruikshank (1792-1878), a British caricaturist and illustrator. His father, Isaac Cruikshank, was a prominent caricaturist of his era who employed both George and his brother Robert in the family’s print factory. By early adolescence, George had already created a large body of work under the tutelage of his father. Despite having other professional aspirations, George continued to work as a caricaturist when his father died in 1811. George, now the principal breadwinner for his mother and sister, sold his drawings to over twenty different print-sellers. That same year, George became the resident caricaturist for the periodical The Scourge: A Monthly Expositor of Imposture and Folly. His early career in caricature was marked by lampooning the Royal Family and satirical takes on the tumultuous politics of Regency London as well as social commentary on day to day life in Georgian England.

His satirical prints could be so devastating that in June 1820, King George IV offered to pay George £100 as long as he pledged “not to caricature His Majesty in any immoral situation.” Cruikshank transitioned to the work of book illustration, joining his brother. Here too, George succeeded, providing illustrations for more than 850 books, including illustrations for several of Charles Dickens’ works.

By 1835, George had secured his fame as England’s most important graphic artist. George, being the preeminent artist of his time, was praised as a “Modern Hogarth”. Capitalizing on his fame, George began his own publication called Cruikshank’s Comic Almanack. The almanack did well until the publication of Punch magazine in 1841 which virtually destroyed Cruikshank’s dominance in the market. The publication finally ceased in 1853.

In the 1840’s, George turned his satirical genius towards the Temperance movement, illustrating pamphlets warning against the evils of drink. He continued in this vein for the next thirty years until his death in 1878.

The cartoons showcased here belong to Cruikshank’s early period of satirical work, yet these cartoons are neither political nor social satire. Instead, Cruikshank turns his satirical view towards the ever-important topic of health. Regency era Englanders were no strangers to suffering and for the health-conscious Brit’s the threat of disease or a bout of a painful malady was always topical. Who hadn’t, at some point or another, felt the pain of a headache or suffered a bout of the colic? Yet despite its universality, the highly subjective experience of pain remains difficult to describe and measure. The visual language of cartoons compensates for the imprecision of language and diagnostic tools through graphic representation. Cruikshank does precisely that in his pieces, The Cholic and The Headache, depicting the sensation of pain while fancifully reimagining its cause.

1 The Cholic, George Cruikshank, 1819, The Hale Scrapbook

While we tend to associate colic with the prolonged periods of intense crying in an otherwise healthy infant, this is only one application of the term. Colic actually refers more generally to pain that starts and stops abruptly; its often gastrointestinal in origin and results from the contraction of muscles around a blockage of a hollow tube such as the colon, the gall bladder, or the ureter.

In The Cholic, two creatures work in tandem to cinch a rope around the waist of a thin elderly woman, who clutches at her waist while shrieking in pain. While her condition is clearly caused by the two sadistic creatures, the portrait upon the wall behind her suggests another cause. The image of the corpulent woman quaffing some gin suggests that overindulgence may be the real cause of this affliction. Interestingly, the clipping of The Cholic found in the Hale Scrapbook differs from the other documented and digitized copies of the print.

Figure 2 The Cholic, George Cruikshank, 1819, The Wellcome Collection

As seen above, the print shows several more imps terrorizing the elderly woman. The demon’s ready pitchforks, sewing needles, and spears to attack the woman while a number of imps on either of the rope have multiplied. Some sources suggest that presence of the demon holding the sewing needle indicates that a tight corset compressing the stomach is the cause of the woman’s colic, making the piece social satire on women’s fashion. I find this to be a somewhat anachronistic interpretation of the print. The Regency Era saw the popularization of the Empire Silhouette, a style that highlights a more natural waist. Accordingly, women wore the short corset, which supported the breasts while leaving the waist and hips free, or a full-length corset with light boning. The kind of tight compressing corsets with heavy boning that sparked health controversies wouldn’t come into style until the mid-1820’s and the “corset question” wouldn’t reach its height until the 1860’s. This timeline doesn’t exactly fit well with the 1819 publication date of the cartoon, but it could be possible edits were made later on to fit the changing fashions; a hypothesis that would support the two different versions of the cartoon.

Figure 3 The Head Ache, George Cruikshank, c. 1819

The companion piece titled The Head Ache shows a similar scene to that of The Cholic. An agonized man is bedeviled by imps, his face contorted in pain, and his eyes rolling back in his head. Two imps drill into his head—one with a bit, the other with an auger. A third demon stands on his shoulder, holding a red-hot poker. Two more imps stand on either side of the man—one blaring a music horn into his ear the other loudly reciting from the book he holds. The empty vial hanging limply from the man’s hand speaks of curatives failing to provide the relief they promised, while the man’s slumped posture and slack limbs show his resignation to the onslaught.

This print succeeds in capturing the differing sensations of a headache, showing pain that ranges from pounding and piercing, to stabbing and burning. Cruikshank even shows the sensitivity to noise a headache sufferer may experience.

The French poet Charles Baudelaire wrote, “The special merit of George Cruikshank… is an inexhaustible abundance of the grotesque… the grotesque flows unceasingly and inevitably from Cruikshank’s pen, like pluperfect rhymes from the pen of a natural poet. Cruikshank’s grotesque is mainly made of extravagant violence of gesture and movement, and explosive expression. All his little characters play their part with fury and boisterousness, like actors in pantomime.” The grotesque elements of Cruikshank’s cartoons help capture the experience of pain so convincingly. The elements Baudelaire highlights are all exquisitely at play in these caricatures, from the sheer agony of the sufferers’ face to the devilish glee each demon exudes with their facial expression and physical form. These medical caricatures do not aim to represent scientific models of disease, but to show the lived experience of the patient. Invisible pains are externalized and exaggerated to a grotesque degree so even one unfamiliar with a specific pain can empathize. At the same time, the comical aspects of these pieces allow the reader to laugh at the absurdity of pain. The humor of the piece isn’t mocking the sufferer. Instead, the laughter it provokes is cathartic. A brief release from pain’s lonely burden, even if only for a moment.

Figure 4 The Gout, James Gillray, 1799, Wellcome Collection

The informative nature of these cartoons is not restricted to medical history as they tell an interesting story about the genealogy of influence in cartooning. For example, compare the image presented above to the ones we’ve already viewed. They bear a striking resemblance, don’t they? Indeed, the British Caricaturist and Printmaker James Gillray, author of the cartoon titled The Gout, was a major influence on Cruikshank’s art. One can see the thematic similarities, such as how both artists personify pain as a devilish external force. As well as technical similarities, such as the cross-hatching used to signify shadows and intensify the scene.

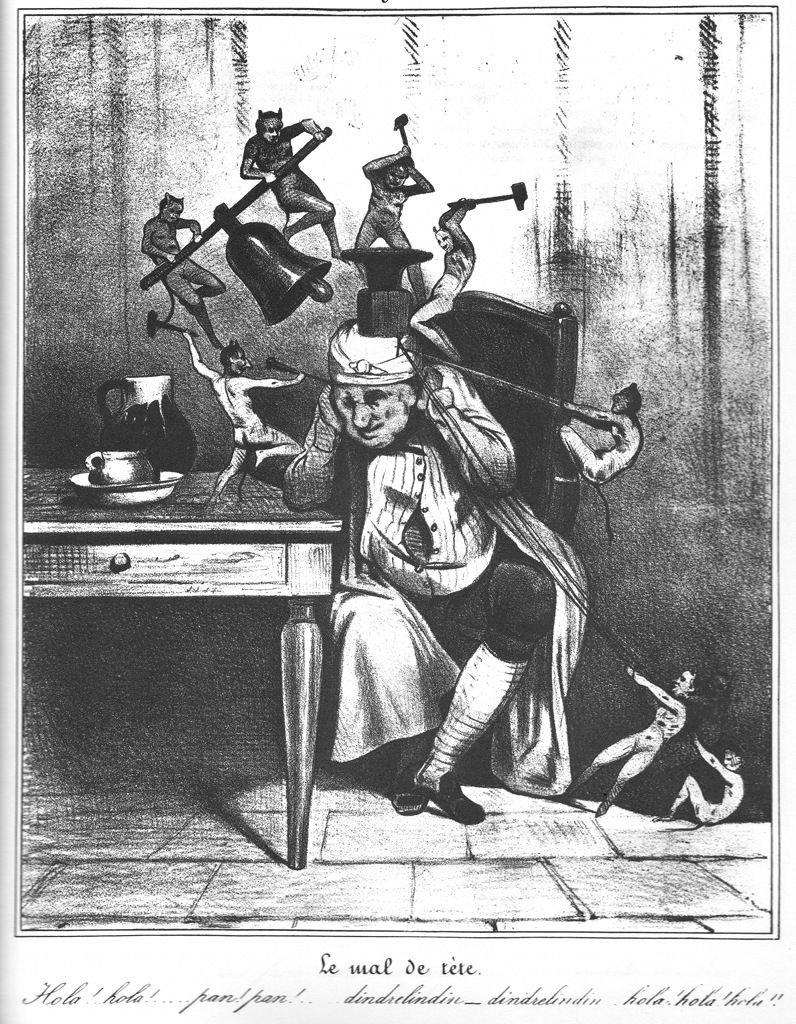

Figure 5 Le mal de tête, Honoré Daumier, 1833, Wellcome Collection

Figure 6 La Colique, Honoré Daumier, 1833, Wellcome Collection

In turn, Cruikshank’s medical caricatures provided inspiration for other artists like the French caricaturist Honoré Daumier. Daumier’s prints, La Colique and Le mal de tête, borrow both their composition and namesake from Cruikshank’s own cartoons.

Altogether, these cartoons tell an interesting tale that interweaves medical history and cartooning, and it is only one of many tales that are out there. If such stories intrigue you, then I suggest you visit the Drawing Blood website to read more like them. We cover a wide range of topics from the Coronavirus epidemic, to the roots of the Anti-vaccination movement, to the etymological origins of Quack doctors!

Recent Comments