Found in the Collection: Udo J. Keppler

by Emily Glassmeyer, BICLM student employee

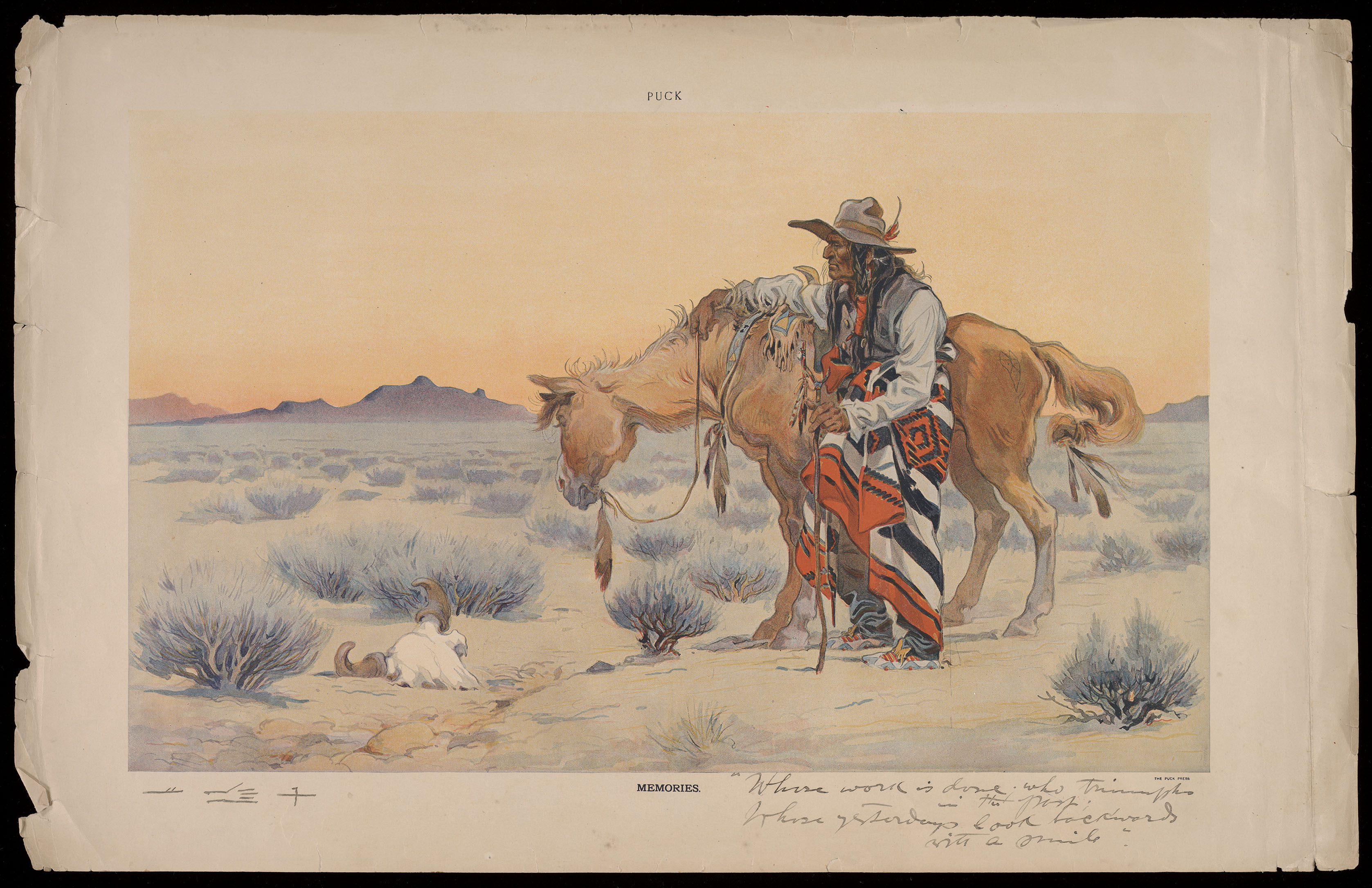

“Memories,” created by Udo J. Keppler in 1910. This piece can be found in the Draper and Sarah Hill Collection at BICLM

One of the greatest pleasures of being a historian who works at BICLM is the access to 19th and 20th century periodicals like Puck and Harper’s Weekly. These volumes give us a glimpse into the lives and perceptions of those of the past – though, their views often did not age well. These periodicals were largely run and read by a white, middle-class, male demographic. As a result, their handling of topics regarding people of color and women are often reliant on distasteful stereotypes and oversimplifications of identities prevalent during the time. However, these tropes were fortunately not ubiquitous across the board.

Joseph Keppler, Sr. founded the American iteration of Puck Magazine following his move to New York in 1872. He passed his love of cartooning and political engagement to his son, Udo J. Keppler, who worked at the magazine with him. While in New York, Udo became richly engrossed in the cultures and practices of the local Seneca tribe of Iroquois. When he took the reins of the magazine in 1894, he merged his advocacy for nationwide women’s suffrage movements with his knowledge of Iroquois culture, best exemplified in the following:

“Savagery to ‘Civilization’,” by Udo. J Keppler. Created in the early 1900s. This piece can be found in the Draper and Sarah Hill Collection at BICLM.

When I first discovered this piece, I was critical of it. Based on what I knew from previous coursework, I was displeased at the implication that these were “rights” of the Iroquois women. On the contrary, they weren’t so much “rights” but inherent facets of their matriarchal culture. To be a woman within Iroquois tribes meant that they were an important trading partner, they played a vital role in medicinal practices, they chose which men would speak in the council and depose those who did not fit their interests, and ultimately, they were the ones responsible for the future of the tribe. It is not that progressive Native American men gave up some of their patriarchal power, but instead that that power was not the focus of their systems, and that the rights of women were inherent to their cultures and traditions. Keppler knew this, and used a simplified image of Iroquois culture to showcase how radically different their treatment of women was from the rhetoric and legislation of the American government

I soon found out that Keppler was embraced by the Seneca people, that he was an honorary chief and a key Native American rights activist. I came to realize that it was not so much that he failed to acknowledge the complexities of Native culture, but instead he knew that in order to make his point digestible to the American public, he had to simplify the realities of Native life and use the prolific rhetoric of the time to push his message– to make it appealing to mainstream white America, who often conceived of Native Americans as backwards. His simplification of Iroquois gender relations was political –all in the hope of encouraging the readership to advocate for change. If these “savages” could do it, why couldn’t they?

Joseph J. Keppler Jr. (Udo J. Keppler) receiving the Seneca Silver Star on September 23, 1937 from Jesse Cornplanter. Image from Cornell University’s Library Native American Collection.

Not only was he fully aware of Iroquois culture, but he had befriended Chief Ed Cornplanter, whose ancestors had been directly involved in the American Revolution. When the Chief died, Keppler fostered an enduring friendship with his son Jesse Cornplanter, who took over his father’s place as chief after returning from WWI. Not only was Jesse the new chief, but he was also a well-regarded artist, performer, informant to scholars and anthropologists, and played a vital role in documenting the histories, mythology, religion and ceremonies of the Iroquois people. Through his advocacy and relationship with Cornplanter, Keppler was well respected within the Seneca Iroquois community. His activist work in cartoons within Puck and elsewhere were of immense importance to their community.

“The Great Spirit,” created by Udo J. Keppler in 1920. This piece can be found in the Draper and Sarah Hill Collection at BICLM.

“The Great Spirit,” created by Udo J. Keppler in 1920. This piece can be found in the Draper and Sarah Hill Collection at BICLM.

Sources & Further Research:

For more information about Udo Keppler & Puck at BICLM, see:

- Udo J. (Joseph Keppler Jr.) Keppler 1872-1956 biographical file

- What fools these mortals be! : the story of Puck : America’s first and most influential magazine of color political cartoons by Michael Alexander Kahn and Richard Samuel West

- Puck (serial)

For more work by Udo Keppler at BICLM, see:

Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum Art Database

For more information on representations of Native American women within the suffrage movement, I recommend The “Other” as Political Symbol: Images of Indians in the Woman Suffrage Movement” by Gail H. Landsman (1992).

History of American Women: http://www.womenhistoryblog.com/2008/05/iroquois-women.html

For more information on Udo Keppler and Jesse Cornplanter’s friendship, see:

http://nac.library.cornell.edu/exhibition/northeast/northeast_6.html

https://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8vd70zm/entire_text/

Recent Comments