This blog post is part of the Frozen Friday Series, an A-Z journey of the Polar Archives. Each week, we will feature some aspect of the history of polar exploration with a blog post written by our student authors.

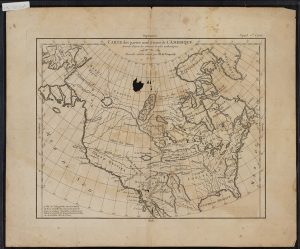

This is one of the oldest maps in the Polar Archives.

Dated at 1772, the map is a French map of colonial

North America, just before the American War for

Independence.

Humanity has by and large completed the map. The Earth has now been effectively mapped out such that there are no major blank spaces labeled with the phrase ‘hic sunt dracones,’ or “here there be dragons.” We take for granted the globe as we know it today. It is easy to forget what it might have been like to wonder what mysteries those unmapped regions held. Just what was beyond that vast amount of water? Could there be a whole new civilization? Prosperous cities with bustling streets? Paradise? Or could there actually be dragons? Imagination may have run wild in the minds of some, out pacing reason. Tales of far off unexplored lands must have been comparable to our contemporary science-fiction vis-à-vis space travel.

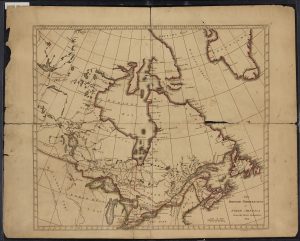

Another of the oldest maps in the Polar Archives,

this map is from 1814 and depicts what is now

eastern Canada.

For most of human history, there was great speculation over a southern continent. This speculation and desire to find it lasted well after the founding of the United States of America. This Terra Australis Incognita (‘southern unknown land’) was conceived as early as the sixth century BCE by Greek philosophers such as Parmenides and Aristotle. The Greeks held that the world is divided into five parallel climate zones: a northern frigid zone, a northern temperate zone, a torrid zone, a southern temperate zone, and a southern frigid zone. Their world, the Mediterranean region and parts of Afro-Eurasia known to them, consisted of the lands in that northern temperate zone. To the south, there must be lands to ensure that the world is not ‘top heavy’. The north and south lands were thought to be divided by a torrid zone, an area of fire and monsters that split the world.[1]

Many nations considered how the mysterious

southern continent might look. This map was

created by Germans.

These ideas of a southern continent persisted, but it was not until the age of European exploration that they were put to the test. As European explorers discovered foreign lands, they created a more complete map. Theories of the nature of the mysterious continent were put forth and ultimately disproved. Africa, long thought to be connected to Terra Australis Incognita, was proved not to be, as Bartholomew Diaz (1488) reached and Vasco da Gama (1498) rounded the Cape of Good Hope. South America too was thought to be connected to Terra Australis Incognita, but Ferdinand Magellan’s voyage through what would be called the Straights of Magellan (1519) and Francis Drakes’ voyage to where the Atlantic meets the Pacific south of Tierra del Fuego (1577) disproved that theory.[2] The idea that Terra Australis Incognita was connected to a larger landmass was killed in the late eighteenth century when Captain James Cook sailed south to find the mysterious continent. Cook spent over three years in unknown southern seas, hoping in vain to find it, unknowingly circling Antarctica. Cook returned to the United Kingdom with proof that Terra Australis Incognita could not be a parallel paradise that had once been dreamt up by the Greeks.[3]

As one might expect, maps have become more

accurate as our technology has improved. However,

perspective can make a great deal of difference, as

this map from 1941 demonstrates.

By and large, Cook marked the end of humanity’s major ignorance of Antarctica. The chapter of Antarctic exploration dominated by myths finally closed. Although there would be further theories about the nature of the Antarctic interior, none would be quite like the mythos of Terra Australis Incognita. In the coming centuries, Antarctica would be revealed to mankind. In those chapters are the tales of Dr. Frederick Cook, Sir Hubert Wilkins, and Admiral Richard E. Byrd. Those and other accounts of polar exploration can be found at the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center Archival Program. Some of those many stories are told here in other Frozen Fridays blog posts.

Written by John Hooton

[1] Antarctica, 2nd ed., s.v. “Terra Australis Incognita.” (Surry Hills: Reader’s Digest, 1990).

[2] Antarctica, “Terra Australis Incognita.”

[3] Antarctica, 2nd ed., s.v. “Antarctica Encircled.” (Surry Hills: Reader’s Digest, 1990).

Recent Comments